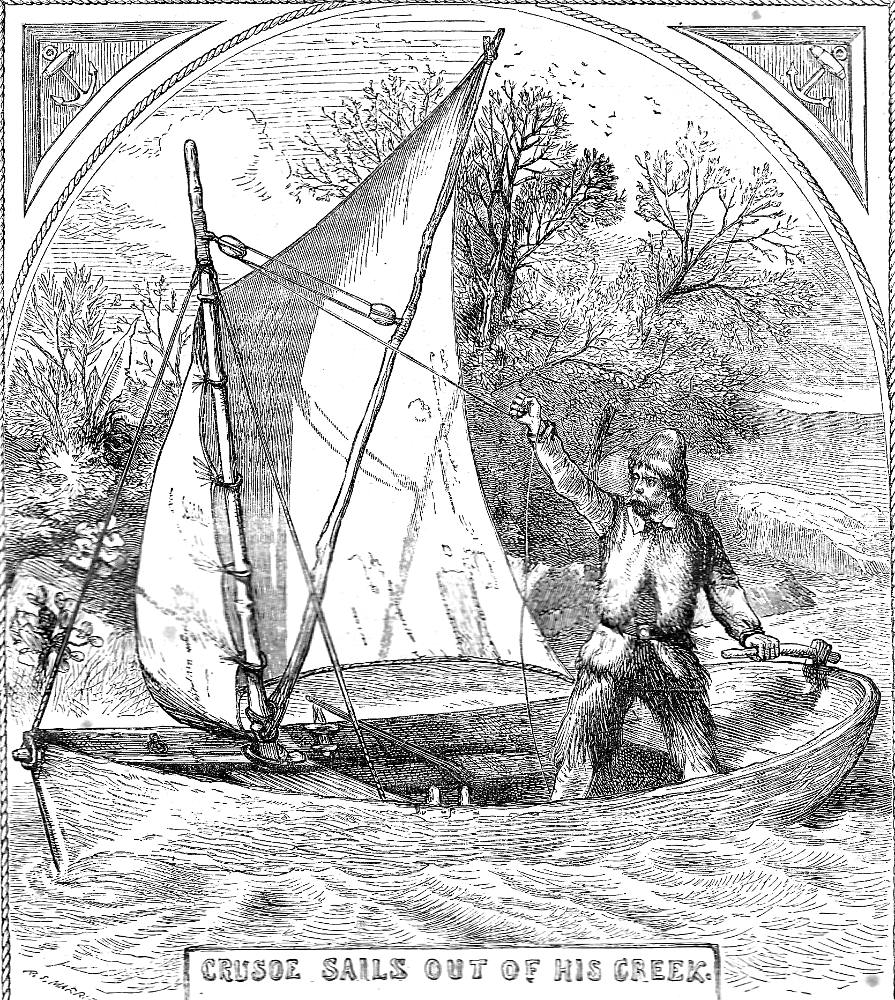

I brought it into the creek

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

half-page lithograph

10.5 cm high by 10.5 cm wide, vignetted.

1891

Robinson Crusoe, embedded on page 100; signed "Wal Paget" lower left.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustration: Crusoe succeeds in launching a canoe

I cannot say that after this, for five years, any extraordinary thing happened to me, but I lived on in the same course, in the same posture and place, as before; the chief things I was employed in, besides my yearly labour of planting my barley and rice, and curing my raisins, of both which I always kept up just enough to have sufficient stock of one year’s provisions beforehand; I say, besides this yearly labour, and my daily pursuit of going out with my gun, I had one labour, to make a canoe, which at last I finished: so that, by digging a canal to it of six feet wide and four feet deep, I brought it into the creek, almost half a mile. As for the first, which was so vastly big, for I made it without considering beforehand, as I ought to have done, how I should be able to launch it, so, never being able to bring it into the water, or bring the water to it, I was obliged to let it lie where it was as a memorandum to teach me to be wiser the next time: indeed, the next time, though I could not get a tree proper for it, and was in a place where I could not get the water to it at any less distance than, as I have said, near half a mile, yet, as I saw it was practicable at last, I never gave it over; and though I was near two years about it, yet I never grudged my labour, in hopes of having a boat to go off to sea at last. [Chapter X, "Tames Goats," pp. 97-98]

Crusoe builds another boat

Crusoe's learning by trial and error is not without its setbacks, but typically he analyzes the nature of the problem and determines how to resolve it. His determination to build a boat in order to explore the island has been the subject of many of the programs of illustration, beginning with Thomas Stothard in 1790. Paget illustrates the failed second attempt, in which Crusoe cannot launch the large canoe that he has taken months to build.

His third major attempt, illustrated by Stothard, proves far more successful because he addressesthe problem of location and, with Friday's advice, chooses a more suitable species of tree with which to construct the hollowed-out canoe. Jean-Jacques Rousseau held up the novel and its resilient protagonist as examples of practical knowledge; however, determined though he may be to find a solution, Crusoe remains a complete amateur at every practical problem he attempts to solve through ingenuity, common sense, and trial-and-error. His motto might well be "If it works, it's good"— but it takes Crusoe several attempts before he is able to launch a boat.

Whereas Defoe is somewhat reflective in his development of the boat-launching narrative as he has his protagonist-narrator reflect on his past errors and upon the wisdom of providence in directing his efforts, Paget as the late nineteenth-century illustrator provides a linear development in the narrative. Exploring the island and assessing its resources in such pictures as I descended a little on the side of that delicious valley (facing page 74), he determines to build a boart, wit the initial objective of exploration, but the ultimate objective of escaping. Not always absolutely correct in his calculations, however, as What odd, misshapen, ugly things I made demonstrates, he persists, and seems to have arrived at the brink of success in I resolved to dig into the surface of the earth. Finally, as the present illustration affirms, he succeeds. The sequel is anything but expected, however, for the wind and currents combine to make his return to the island difficult. Thus, Paget converts over thirty pages of letterpress into an effective story-board into just five illustrations.

The visual progress from boat construction to successful second landing

- "I descended a little on the side of that delicious valley."

- "What odd, misshapen, ugly things I made."

- "I resolved to dig into the surface of the earth."

- "I brought it into the creek."

- "I fell on my knees."

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Related Scenes from Stothard (1790), Cruikshank (1831), Wehnert (1862), and Cassell's (1863)

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of the formerly solitary protagonist now working alongside the ultimate "practical human being," the Noble Savage, Friday: Robinson Crusoe and Friday making a boat. (Chapter XVI, "Rescue of the Prisoners from the Cannibals," copper-engraving). Centre: The parallel scene from the Cassell's Illustrated edition, Crusoe makes a Boat, in which Crusoe looks a little discouraged (1863). Right:Wehnert's vigorous colonist fells trees, learning "on the job" how to make a single board out a tree, Felling trees for planks (1862). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Theparallel scene from Cruikshank's illustrations for the 1831 John Major

edition,

Theparallel scene from the Cassell illustrations for the 1863-64,

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Walter

Paget

Next

Last modified 30 April 2018