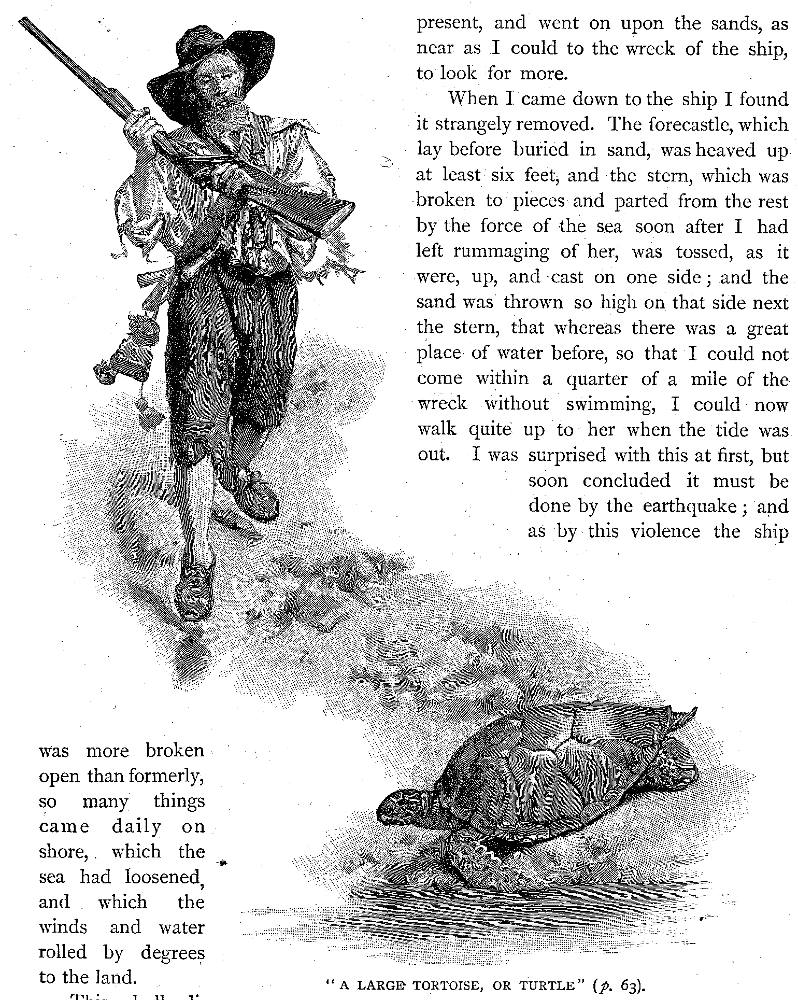

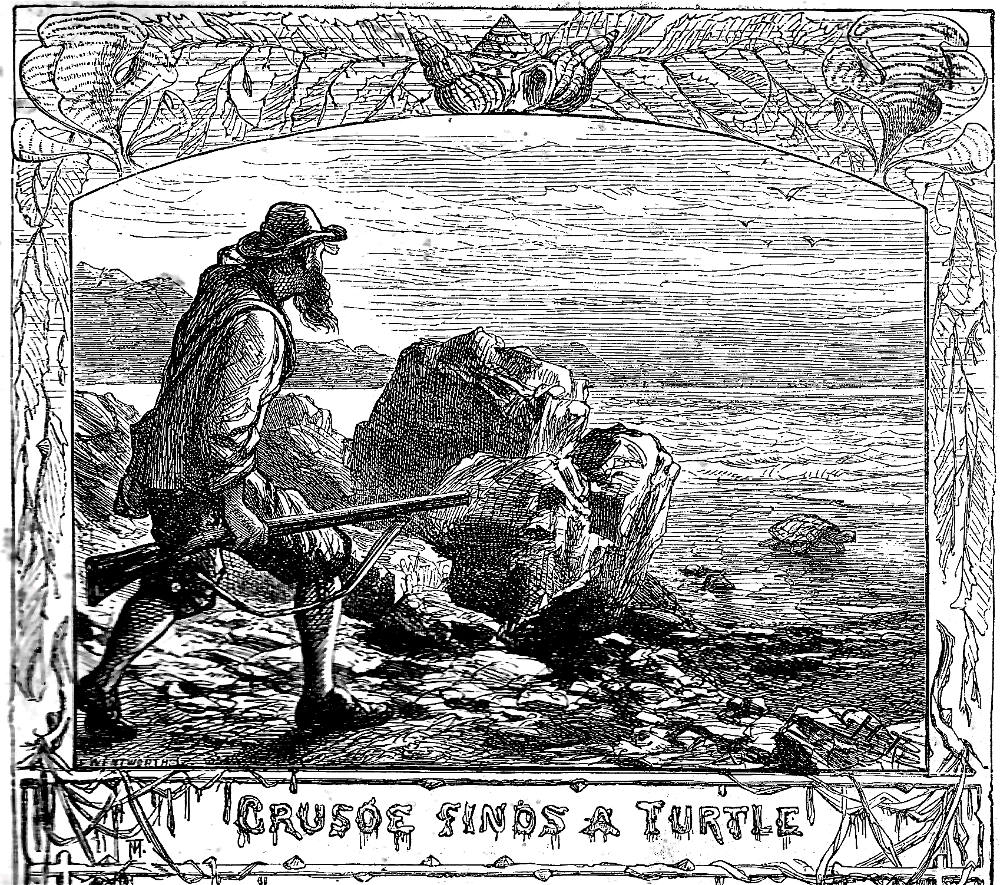

A large tortoise, or turtle (p. 63), page 61, facing the vignette I Caught a Young Dolphin (p. 62) — complementary proleptic illustrations for Part One, Chapter VI, "Ill and Conscience-Stricken" in The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, illustrated by Wal Paget (1891). Lithograph, 15.8 cm high x 12 cm wide, vignetted. The rifle points the reader back towards the facing page, even as the diagonals of the complementary plates draw the reader's eye upward to the images of Crusoe.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Related material: Pages 60-61 as complementary illustrations

Passage Anticipated: Crusoe the Fisherman

June 16. — Going down to the seaside, I found a large tortoise or turtle. This was the first I had seen, which, it seems, was only my misfortune, not any defect of the place, or scarcity; for had I happened to be on the other side of the island, I might have had hundreds of them every day, as I found afterwards; but perhaps had paid dear enough for them. [Chapter VI, "Ill and Conscience Stricken," page 63]

Commentary: Paget's Visual Experimentation

The late nineteenth-century illustrator experimented with using the existing print technology and the medium of the lithograph to produce an interesting fusion of print-medium and visual texts. Here, Paget creates a pair of complementary, large-scale vignettes on facing pages that compel the reader to anticipate the scenes as Defoe describes them several pages later. The effect is startling in that the reader receives two images of the protagonist simultaneously, admiring his resilience and resourcefulness in exploiting the potential food supply which the island affords the castaway. Previous programs of illustration, in contrast, do not depict Crusoe as a fisherman, although the earlier Cassell edition does depict Crusoe discovering a tortoise (the emphasis there being on Crusoe and the seashore rather than the creature). The proleptic effect combined the terseness of the journal account privileges the beautifully detailed, large-scale vignette over the bare prose passage realised.

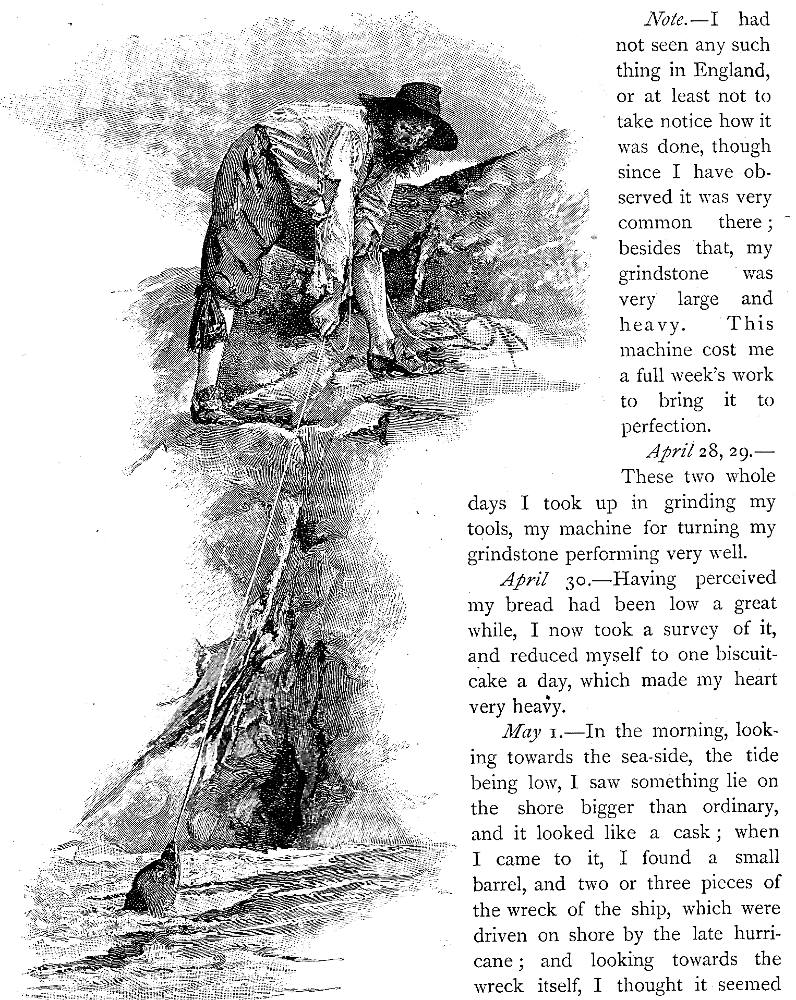

Here again, the complementary illustrations impose themselves on the text, asserting their dominance on the printed page by compelling the text to retreat into three uneven columns of print opposite Crusoe and his prey. The effect of shrinking the width of the text columns is to diminish their importance (after all, they concern neither the dolphin nor the turtle) and to focus on the relationship between the environment and the castaway, who completely embraces the life of action that his situation imposes upon him. This asymetrical relationship is not entirely new to nineteenth-century publishing practice as Dickens's illustrators, for example, had employed it in dropping wood-engravings in the texts of the Christmas Books that followed the more conventionally laid out A Christmas Carol of 1843. Moreover, Paget here uses the strategy of the complementary vignettes dropped into the text to show readers two distinct actions as occurring simultaneously, underscoring Crusoe's energy and determination to survive, even though these actions (fishing for dolphins and hunting for turtles) occur sequentially. Paget may have seen the interesting fusion of sequential events that John Leech achieved in Sir Joseph Bowley's, which shows the protagonist both in the foyer (below) and in the Bowleys' parlour (above) within the same frame. Paget renders his presentation highly credible through details of seventeenth-century male attire such as the breeches, linen short, broad-brimmed felt hat and bandolier, as well as through his highly realistic renderings of the creatures that Crusoe is hunting. Juxtaposing the fishing scenes against the text involving Crusoe's returning to salvage material from the wreck in fact creates the impression of Crusoe's being in two different places and doing two separate things at once. The closest approximation of the effect that Paget creates occurs in the Tenniel illustrations for The Haunted Man (1848), in which facing pages present complementary images in Illustrated Double-Page to Chap. II (pp. 52-53) with Mrs. Tetterby and her brood to the left and Redlaw, ascending the staircase from the parlour to the student's rooms, right.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant image from the earlier Cassell edition

Above: The earlier Cassell's version of Crusoe'scatching a large

sea-turtle for dinner, De Foe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising

Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards

of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64. Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising

Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With

upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,

and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891. Last modified 27 April 2018References