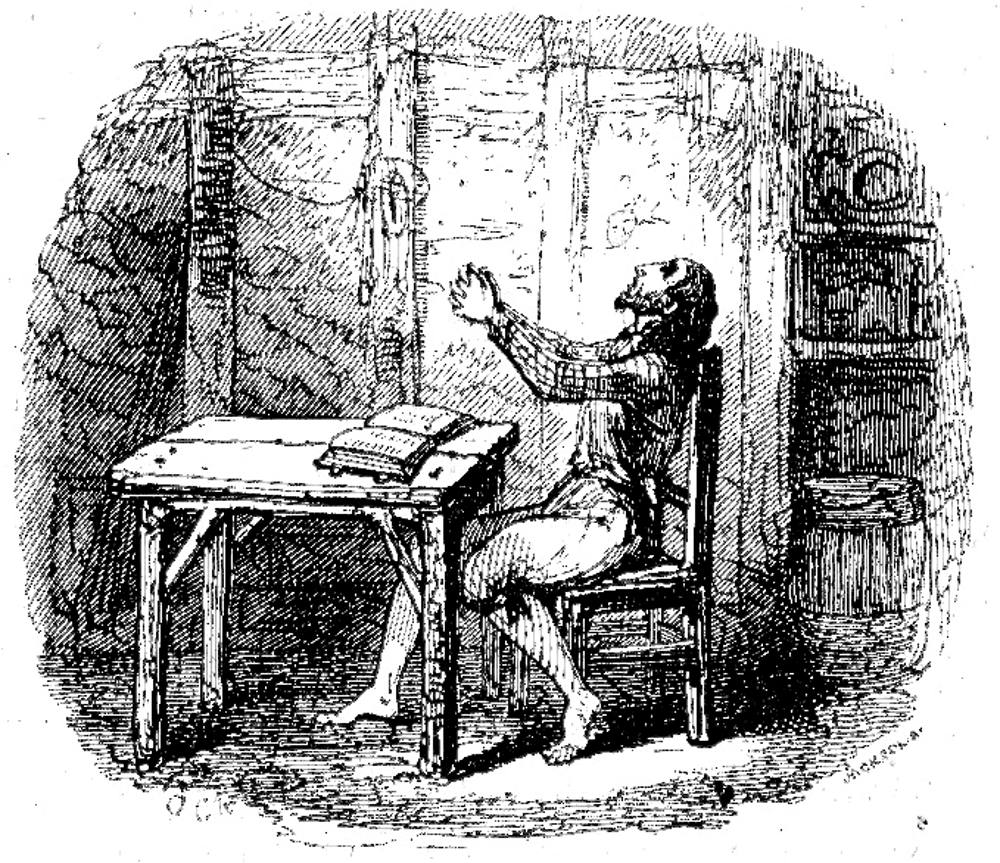

Broiled it on the coals (p. 67) contrasts the active Crusoe who by daylight has explored the island and exploited its resources. Paget develops this night scene as a closeup of the alienated castaway who looks in the coals, pondering his future. Already his short looks ragged, as if reflecting his anxieties about surviving as a civilised person on this uninhabited island so far from England. Middle of page 65, vignetted: approximately 11 cm high by 12 cm wide, unsigned.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: The Reflective Crusoe

June 28. — Having been somewhat refreshed with the sleep I had had, and the fit being entirely off, I got up; and though the fright and terror of my dream was very great, yet I considered that the fit of the ague would return again the next day, and now was my time to get something to refresh and support myself when I should be ill; and the first thing I did, I filled a large square case-bottle with water, and set it upon my table, in reach of my bed; and to take off the chill or aguish disposition of the water, I put about a quarter of a pint of rum into it, and mixed them together. Then I got me a piece of the goat’s flesh and broiled it on the coals, but could eat very little. I walked about, but was very weak, and withal very sad and heavy-hearted under a sense of my miserable condition, dreading, the return of my distemper the next day. At night I made my supper of three of the turtle’s eggs, which I roasted in the ashes, and ate, as we call it, in the shell, and this was the first bit of meat I had ever asked God’s blessing to, that I could remember, in my whole life. After I had eaten I tried to walk, but found myself so weak that I could hardly carry a gun, for I never went out without that; so I went but a little way, and sat down upon the ground, looking out upon the sea, which was just before me, and very calm and smooth. As I sat here some such thoughts as these occurred to me: What is this earth and sea, of which I have seen so much? Whence is it produced? And what am I, and all the other creatures wild and tame, human and brutal? Whence are we? Sure we are all made by some secret Power, who formed the earth and sea, the air and sky. And who is that? Then it followed most naturally, it is God that has made all. Well, but then it came on strangely, if God has made all these things, He guides and governs them all, and all things that concern them; for the Power that could make all things must certainly have power to guide and direct them. If so, nothing can happen in the great circuit of His works, either without His knowledge or appointment. [Chapter VII, "Ill and Conscience-Stricken," pp. 67-67]

Commentary

Convinced that God is punishing him for failing to honour the will of his parents, Crusoe interprets his many vicissitudes as a test of his worthiness to be forgiven. He has looked heavenward from the open Bible as he prays aloud, implying his personal piety and Puritan upbringing, for he never questions the existence or mercy of God. Cruikshank's handling seems a little melodramatic, as if he is recording the scene from a stage adaptation, with Crusoe gesturing heavenward in a crisis of conscience. In a mood quite different from that f the recent illustrations, a pensive rather than an active Crusoe wears no hat and carries no gun; moreover, Paget has not included the gun and bandolier, as if to underscore Crusoe's alienation and vulnerability in this unfamiliar if not hostile environment. He is now explicitly not sleeping in a tree, but has fashioned a permanent shelter for himself.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Parallel Scenes from Other nineteenth-century Series

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of the solitary and reflective protagonist, Robinson Crusoe at work in his cave (Chapter IV, "First Few Weeks on the Island," copper-engraving). Centre: The children's book illustration that exemplifies Crusoe's personal piety, Robinson Crusoe reading the Bible (1818). Right: Wehnert's more psychological interpretation of Crusoe's spirituality, Crusoe's dream (1862). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above:Cruikshank's dramatic(and perhaps overly dramatic) wood-engraving of Crusoe'scrisis of conscience,"Jesus, thou son of David! Jesus, thou exalted Prince and Saviour! give me repentance!" (1831).

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 28 April 2018