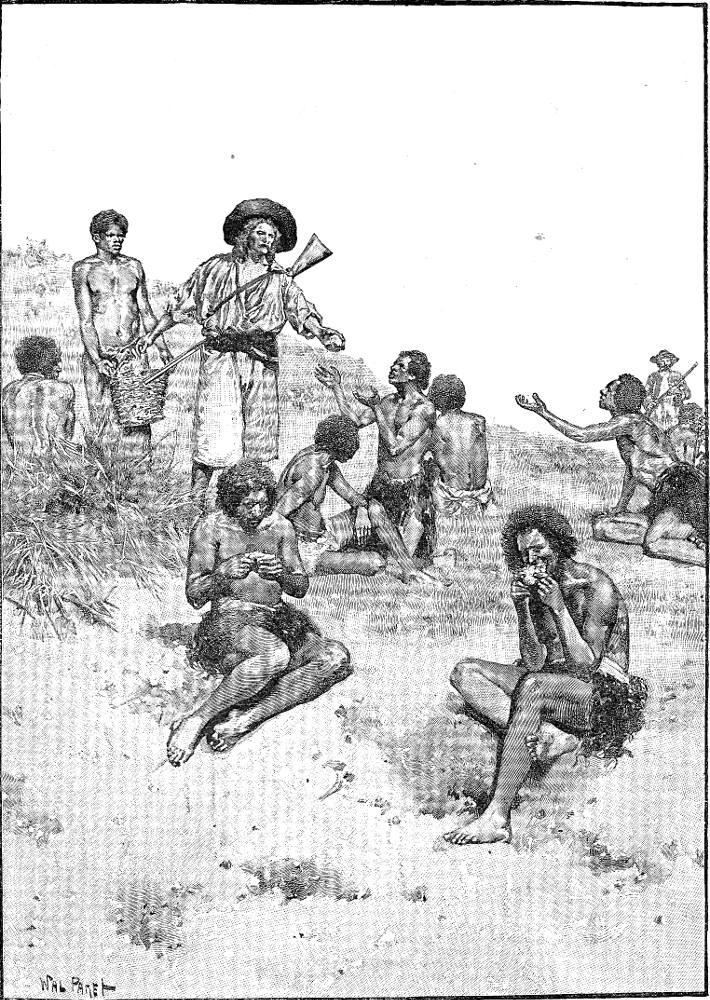

Ate their provisions very thankfully

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

lithograph

18 cm high by 12.9 cm wide, framed.

1891

Robinson Crusoe, facing page 287.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: The Europeans are Merciful to the Vanquished

It was some while before any of them could be taken; but being weak and half-starved, one of them was at last surprised and made a prisoner. He was sullen at first, and would neither eat nor drink; but finding himself kindly used, and victuals given to him, and no violence offered him, he at last grew tractable, and came to himself. They often brought old Friday to talk to him, who always told him how kind the others would be to them all; that they would not only save their lives, but give them part of the island to live in, provided they would give satisfaction that they would keep in their own bounds, and not come beyond it to injure or prejudice others; and that they should have corn given them to plant and make it grow for their bread, and some bread given them for their present subsistence; and old Friday bade the fellow go and talk with the rest of his countrymen, and see what they said to it; assuring them that, if they did not agree immediately, they should be all destroyed.

The poor wretches, thoroughly humbled, and reduced in number to about thirty-seven, closed with the proposal at the first offer, and begged to have some food given them; upon which twelve Spaniards and two Englishmen, well armed, with three Indian slaves and old Friday, marched to the place where they were. The three Indian slaves carried them a large quantity of bread, some rice boiled up to cakes and dried in the sun, and three live goats; and they were ordered to go to the side of a hill, where they sat down, ate their provisions very thankfully, and were the most faithful fellows to their words that could be thought of; for, except when they came to beg victuals and directions, they never came out of their bounds; and there they lived when I came to the island and I went to see them. They had taught them both to plant corn, make bread, breed tame goats, and milk them: they wanted nothing but wives in order for them soon to become a nation. They were confined to a neck of land, surrounded with high rocks behind them, and lying plain towards the sea before them, on the south-east corner of the island. They had land enough, and it was very good and fruitful; about a mile and a half broad, and three or four miles in length. Our men taught them to make wooden spades, such as I made for myself, and gave among them twelve hatchets and three or four knives; and there they lived, the most subjected, innocent creatures that ever were heard of. [Chapter V, "A Great Victory," page 284]

Commentary

The text illustrated, which demonstrates the magnanimous nature of the Spanish victors, is actually situated opposite a scene of wanton slaughter, as the settlers' slaves despatch those warriors still lying on the field of battle. Whereas William Luson Thomas in the 1864 battle scene conceives of the warriors as American aboriginals with feathers in their hair, Paget inclines towards a markedly negroid interpretation of the mainland aboriginals, as in "Came ranging along the shore."

Ironically, because the English and Spanish plantation-owners feel that they have enough slaves, the settlers provide the defeated aboriginal warriors with a reservation and sufficient supplies to feed themselves and start their own plantation — presumably to wean them away from cannibalism, but also to contain them, to prevent their re-arming, and to restrict their communications with the mainland of South America, which probably remains a potential threat to the island colony. Defoe's original readers would undoubtedly have regarded the book's view of slavery as enlightened and humanitarian, whereas nineteenth-century readers would have regarded the institution of slavery as uncivilised since it had been abolished in Britain itself in 1807, and elsewhere in the Empire in 1833, and since a great war had been fought in the former American colonies over the same issue from 1860 to 1865. The armed overseer in the illustration (looking very much like Paget's rendition of Will Atkins) would have been a palpable reminder of the Antebellum Southern United States in Harriet Beecher Stowe's best-seller in Great Britain Uncle Tom's Cabin (London: Cassell, 1852), which George Housman Thomas illustrated. He was, by coincidence, one of the team of artists behind the Cassell's illustrations of the 1863-64 edition of Robinson Crusoe.

Neil Heims (1983) relates Crusoe's abhorrence of the cannibalism by the indigenous population of the mainland opposite the island with his previous involvement in the slave trade, an equally abhorrent practice that treats human beings as cattle:

The confounding irony which reveals a serious identity between Crusoe and

the cannibals, however, and accounts for the split the fable effects between them, and

for his strong antagonism to them, is that Crusoe set out on the adventure that cast him

upon the island for twenty-eight years in order to be a trafficker in Negro slaves. The

savagery of this act of consuming and devouring, in order to be denied for the sake of

the European conscience, was displaced onto the blacks themselves by inventing a fable

that focuses on the more blatant savagery of a simpler cannibalism attributed to them. In

Related Material

- The Anti-Slavery Campaign in Britain

- J. M. W. Turner's Slave Ship. [Full title: Slavers Overthrowing the Dead and Dying — Typho[on]n Coming On.]

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Heims, Neil. "Robinson Crusoe and the Fear of Being Eaten." Colby Library Quarterly,Volume 19, Issue 4 (December 1983). Pp. 190-193. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://search.yahoo.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2528&context=cq

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Walter

Paget

Next

Last modified 7 April 2018