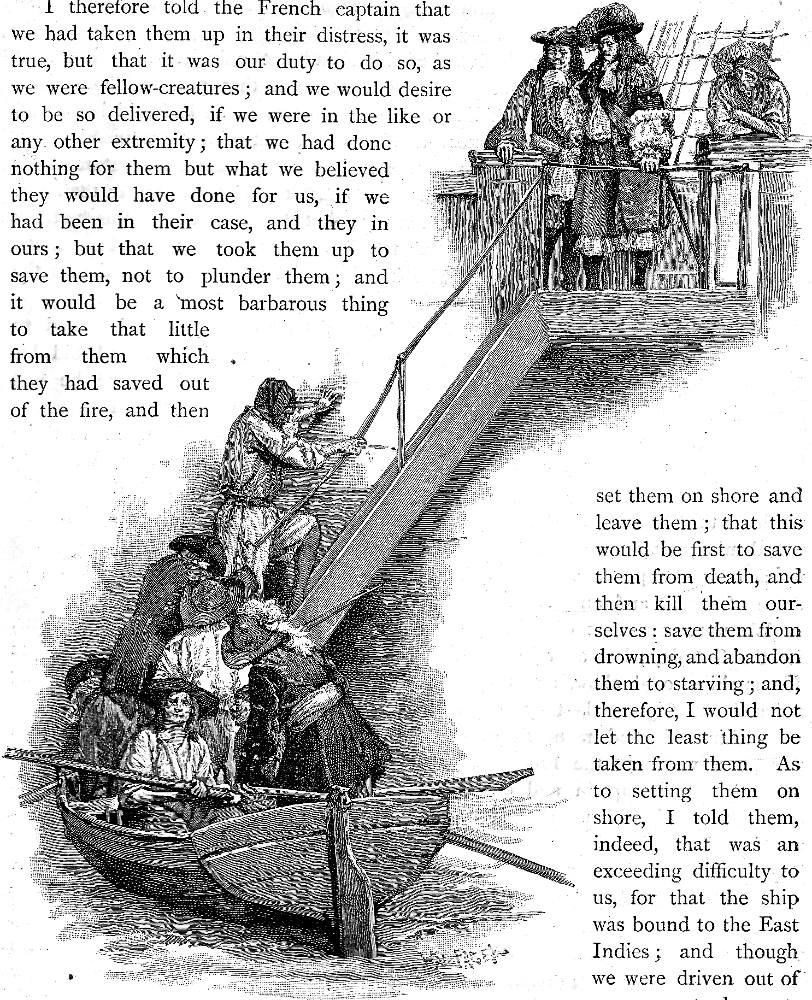

The mate brought six men with him

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

lithograph dropped into the letter-press

15.4 cm high by 12.5 cm wide, vignetted.

1891

Robinson Crusoe (1891): page 232.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Wal Paget —> Next]

The mate brought six men with him

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

lithograph dropped into the letter-press

15.4 cm high by 12.5 cm wide, vignetted.

1891

Robinson Crusoe (1891): page 232.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

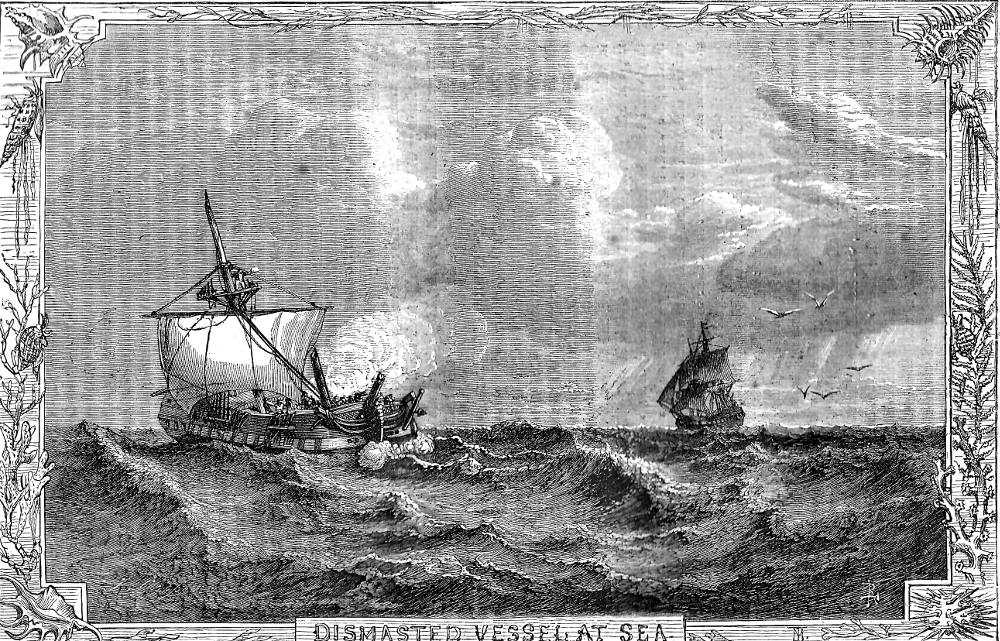

It was in the latitude of 27 degrees 5 minutes north, on the 19th day of March 1694-95, when we spied a sail, our course S. E. and by S. We soon perceived it was a large vessel, and that she bore up to us, but could not at first know what to make of her, till, after coming a little nearer, we found she had lost her main-topmast, fore-mast, and bowsprit; and presently she fired a gun as a signal of distress. The weather was pretty good, wind at NNW. a fresh gale, and we soon came to speak with her.

We found her a ship of Bristol, bound home from Barbadoes, but had been blown out of the road at Barbadoes a few days before she was ready to sail, by a terrible hurricane, while the captain and chief mate were both gone on shore; so that, besides the terror of the storm, they were in an indifferent case for good mariners to bring the ship home. They had been already nine weeks at sea, and had met with another terrible storm, after the hurricane was over, which had blown them quite out of their knowledge to the westward, and in which they lost their masts. They told us they expected to have seen the Bahama Islands, but were then driven away again to the south-east, by a strong gale of wind at N.N.W., the same that blew now: and having no sails to work the ship with but a main course, and a kind of square sail upon a jury fore-mast, which they had set up, they could not lie near the wind, but were endeavouring to stand away for the Canaries.

. . . . We immediately applied ourselves to give them what relief we could spare; and indeed I had so far overruled things with my nephew, that I would have victualled them though we had gone away to Virginia, or any other part of the coast of America, to have supplied ourselves; but there was no necessity for that.

But now they were in a new danger; for they were afraid of eating too much, even of that little we gave them. The mate, or commander, brought six men with him in his boat; but these poor wretches looked like skeletons, and were so weak that they could hardly sit to their oars. The mate himself was very ill, and half starved; for he declared he had reserved nothing from the men, and went share and share alike with them in every bit they ate. [Chapter II, "Intervening History of the Colony," pp. 234-35]

The illustration in the earlier Cassell edition had emphasized the ship's distress, that is, the vessel's impaired state. Here, instead of a full-page seascape, Paget focusses upon the effect that the ship's troubles have had on the crew. The vessel is in distress as a consequence of a hurricane, the destruction of its main mast, the crew's being in unfamiliar waters, and above all a dire shortage of food. However, as the text indicates, the weather is now fair; no waves engulf the vessel, and drowning sailors do not cling to the spars floating in the foreground. In other words, to make sense of the illustration the viewer must move forward two pages to read the text, and discover which figure represents Crusoe. As Crusoe had come to the rescue of Friday, the Spaniard, and the victims of the mutiny in Part One, he extends his sympathy to the oppressed and suffering. The lithograph prepares the reader for Crusoe's coming to the assistance of those on the dismasted vessel with supplies, although the illustration does not reveal the nature of the distress of the passengers and crew, which apparently is the result of some sort of tropical virus, a shortage of food, and near-starvation. The accompanying text clarifies the identities of the figures: the six men in the shore-boat are from the derelict vessel, and Crusoe is, in all likelihood, the figure in the embroidered greatcoat and plumed hat at the top of the landing. Paget provides visual continuity by having him appear in precisely the same clothing when he arrives on the island, in "'Do you not know me?'" (facing page 242).

Above: The 1864 edition's woodblock engraving of the distressed vessel, off-course and without a main mast: Dismasted Vessel at Sea. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 27 March 2018