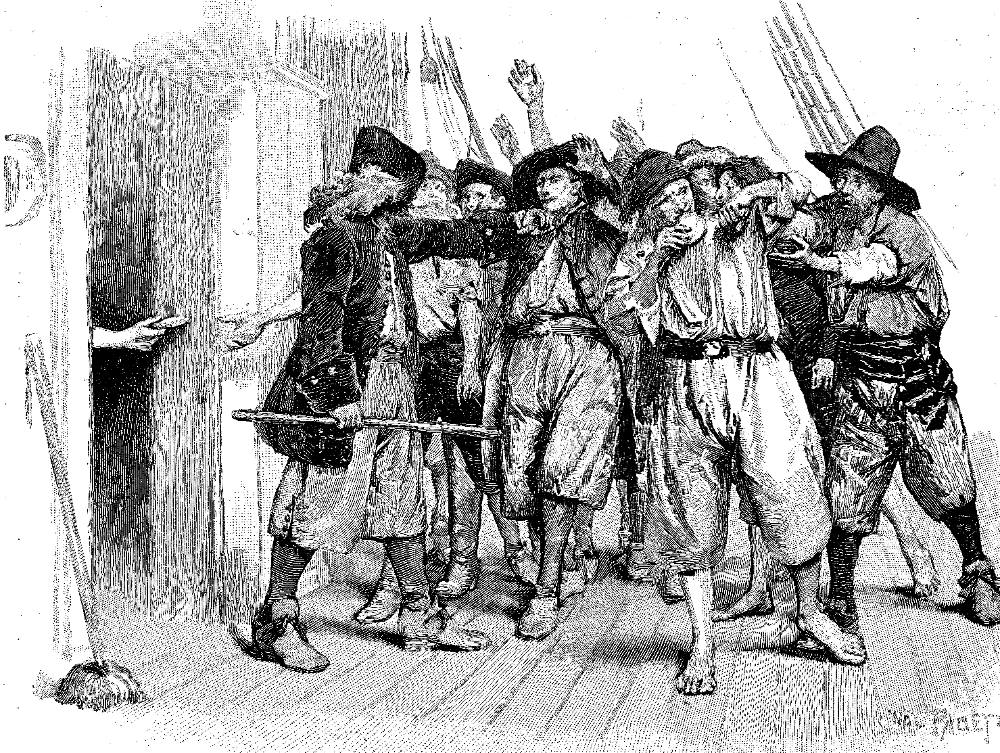

I found the poor men on board almost in a tumult. (See p. 236), signed by Wal Paget, bottom right. Paget has positioned the sailor attempting to eat a piece of hardtack just to the right of centre, juxtaposed against Crusoe's mate, who is attempting to maintain order at the cookhouse door (left). One-half of page 237, vignetted: 8.7 cm high by 12.3 cm wide. Running head: "The Starving Crew" (page 237).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: Disaster at Sea in Human Terms

I found the poor men on board almost in a tumult to get the victuals out of the boiler before it was ready; but my mate observed his orders, and kept a good guard at the cook-room door, and the man he placed there, after using all possible persuasion to have patience, kept them off by force; however, he caused some biscuit-cakes to be dipped in the pot, and softened with the liquor of the meat, which they called brewis, and gave them every one some to stay their stomachs, and told them it was for their own safety that he was obliged to give them but little at a time. But it was all in vain; and had I not come on board, and their own commander and officers with me, and with good words, and some threats also of giving them no more, I believe they would have broken into the cook-room by force, and torn the meat out of the furnace — for words are indeed of very small force to a hungry belly; however, we pacified them, and fed them gradually and cautiously at first, and the next time gave them more, and at last filled their bellies, and the men did well enough.

But the misery of the poor passengers in the cabin was of another nature, and far beyond the rest; for as, first, the ship’s company had so little for themselves, it was but too true that they had at first kept them very low, and at last totally neglected them: so that for six or seven days it might be said they had really no food at all, and for several days before very little. [Chapter I, "Revisits the Island," page 236]

Commentary: The Crew, not the Ship

The illustration in the earlier Cassell edition had emphasized the ship's distress, that is, the vessel's impaired state. Here, instead of a full-page seascape, Paget focusses upon the effect that the ship's troubles have had on the crew. The vessel is in distress as a consequence of a hurricane, the destruction of its masts, the crew's being in unfamiliar waters, and above all a dire shortage of food. However, as the text indicates, the weather is now fair; no waves engulf the vessel, and drowning sailors do not cling to the spars floating in the foreground. In other words, to make sense of the illustration the viewer must consult the facing page just read, in order to discover which figure represents Crusoe — in fact, only his mate appears in the illustration. As Crusoe had come to the rescue of Friday, the Spaniard, and the victims of the mutiny in Part One, he extends his sympathy to the oppressed and suffering, first to those on board the Quebec merchantman ands now to those on this ship bound for Bristol from Barbadoes. The lithograph elaborates upon Crusoe's coming to the assistance of those on the dismasted vessel with supplies, although the illustration does not reveal the nature of the distress of the passengers and crew, which apparently is the result of some sort of tropical virus, a shortage of food, and near-starvation. The accompanying text clarifies the nature of the action and the meaning of "tumult" in the caption. However, the illustration does not show Crusoe directing the relief operation, signalling that in the action of Part Two he will be a reporter and strategist rather than an actor.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Exciting Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, as Related by Himself. With 120 original illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris,and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 27 March 2018