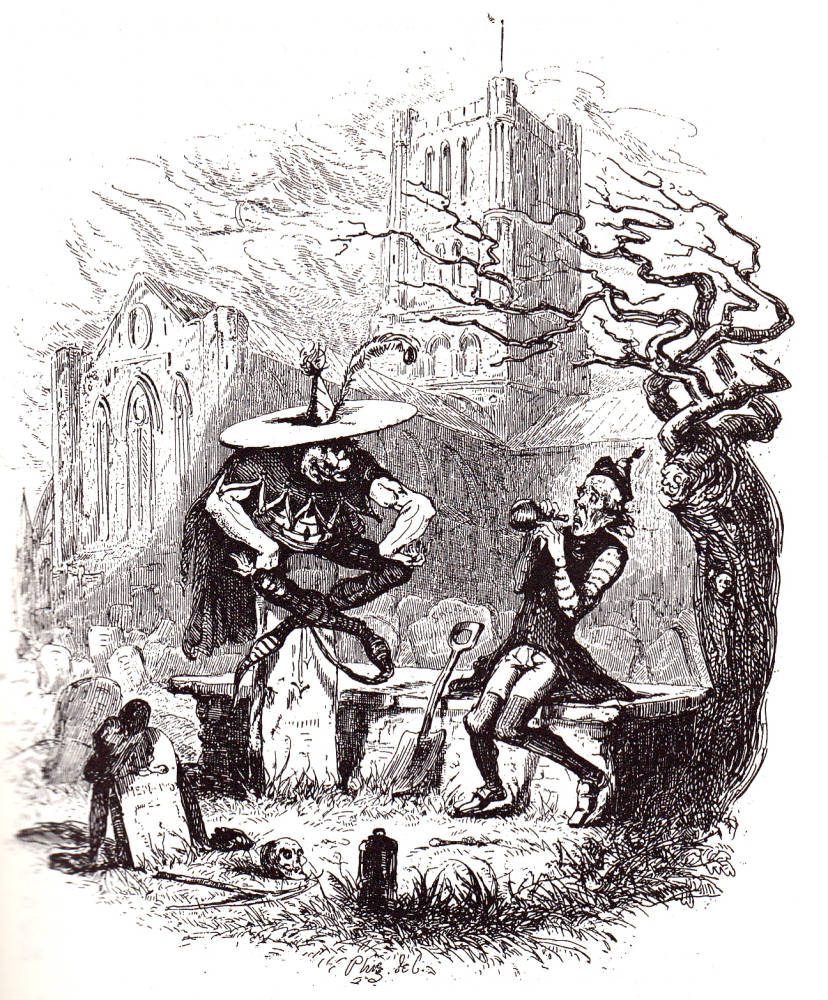

"His eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold" (the Goblin King confronts the misanthropic Gabriel Grub in the country churchyard) in Chapter XXIX, "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton," page 172.

Bibliographical Notes

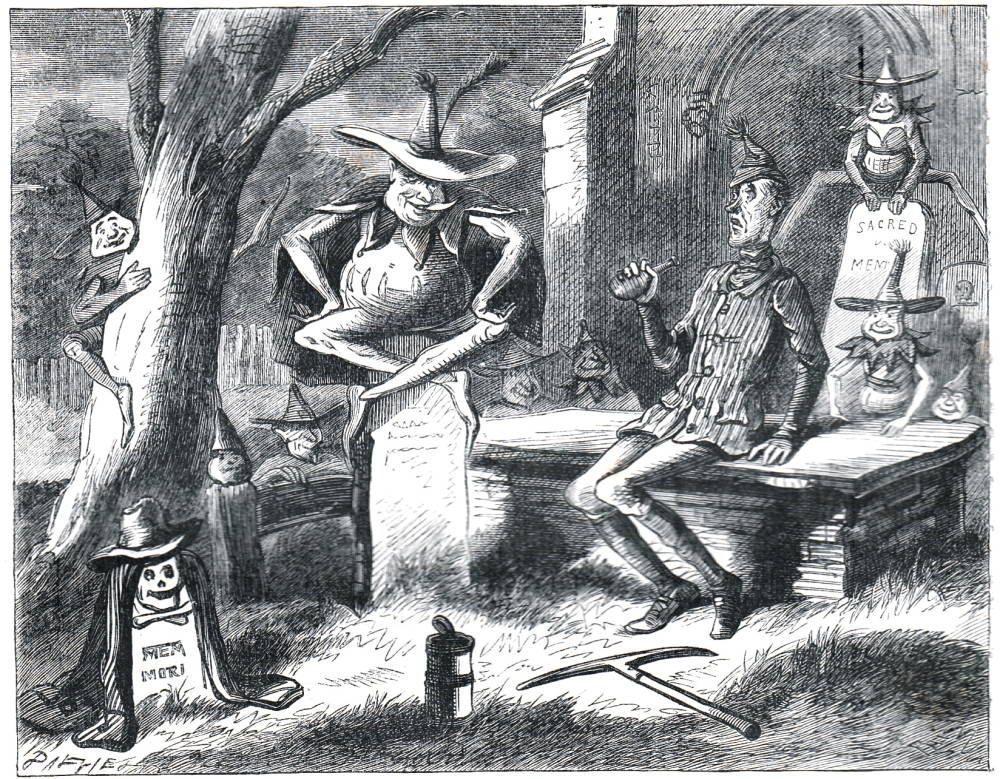

Thanks in part to Phiz's humorous but weird serial illustration (see right), the interpolated short story of the supernatural remains among the most memorable in Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club. Chapter XXIX, "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton," first appeared as the last of three chapters in the tenth monthly part with the Phiz engraving of the sexton and the Goblin King in January 1837. Nast may not have seen Phiz's re-working of this whimsical illustration as a composite woodblock engraving for the Chapman and Hall Household Edition, issued in 1874 but prepared for the press somewhat earlier. Nast's re-working of the original steel engraving nevertheless acknowledges the original in the American illustrator's choice of the moment realised and the juxtaposition of the Goblin King, the quailing sexton, and the tombstone. Half-page composite woodblock-engraving, 4 1⁄8 inches high by 5 ¼ inches wide (10.4 cm high by 13.4 cm wide), framed; referencing text on page 171; descriptive headlines: "Larcenous Goblins" (p. 171) and "Gabriel Grub Wanted" (p. 173). Many critics see in the tale of Gabriel Grubb and the goblins the prototype of A Christmas Carol (1843).

Over the course of the nineteenth century leading illustrators on either side of the Atlantic produced a number of narrative-pictorial programs; however, in none of these are the interpolated tales consistently illustrated. Even the great comic re-interpreter of Dickens for the twentieth century, Harry Furniss, did not attempt to illustrate this particular story. However, not surprisingly, given its strong visual appeal, out of all nine interpolated tales "The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton" has been the subject preferred among Dickens's nineteenth-century illustrators.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: A Supernatural Encounter of the Humorous Kind

Not the faintest rustle broke the profound tranquillity of the solemn scene. Sound itself appeared to be frozen up, all was so cold and still.

"It was the echoes," said Gabriel Grub, raising the bottle to his lips again.

"It was not," said a deep voice.

Gabriel started up, and stood rooted to the spot with astonishment and terror; for his eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold.

Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange, unearthly figure, whom Gabriel felt at once, was no being of this world. His long, fantastic legs which might have reached the ground, were cocked up, and crossed after a quaint, fantastic fashion; his sinewy arms were bare; and his hands rested on his knees. On his short, round body, he wore a close covering, ornamented with small slashes; a short cloak dangled at his back; the collar was cut into curious peaks, which served the goblin in lieu of ruff or neckerchief; and his shoes curled up at his toes into long points. On his head, he wore a broad-brimmed sugar-loaf hat, garnished with a single feather. The hat was covered with the white frost; and the goblin looked as if he had sat on the same tombstone very comfortably, for two or three hundred years. He was sitting perfectly still; his tongue was put out, as if in derision; and he was grinning at Gabriel Grub with such a grin as only a goblin could call up. [Chapter XXIX, "The Story of Some Goblins who Stole a Sexton," pp. 171-172]

Commentary: A Christmas Ghost Story told at Dingley Dell, Manor Farm

"The Goblin and The Sexton," first published in the Chapman and Hall serial's January 1837 monthly number, remains a fascinating blend of the weird and macabre on the one hand, and of the comic and whimsical on the other. In choosing this subject for illustration four decades after the appearance of Phiz's steel-engraving, Nast seized upon a narrative moment that would allow him to showcase his talents as a cartoonist and visual story-teller. The tomb and gnarled tree, both derived from the 1837 plate, admirably set the mood; the American Household Edition illustrator has apparently lifted these details from the Phiz original. Nast's Goblin King in His eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold (p. 172) is fantastic yet laughable in his almost pinata-like rotundity and exaggerated facial expression. However, Nast's catatonic Gabriel Grub is surprisingly impressionistic for a period that valued realism in illustration. This terrified sexton is hardly the figure of fun that Phiz's Grub constitutes in Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange unearthly figure (Household Edition, p. 171: see below).

How well has Nast actually realised the weird scene that is the central moment in the Christmas ghost story? Nast has attempted to reiterate the original Phiz engraving's backdrop, with a square-towered church, a porch, and surrounding cemetery; however, the ecclesiastical edifice seems lacking in perspective — it is simply too small to be a village church, let alone the building upon which Phiz based his backdrop, the abbey church at St. Alban's.

Minimizing background detail to present a less cluttered composition, Nast has also shifted the relative positions of the garish supernatural visitor and the rigid sexton from the 1837 original, placing in the foreground the errant mortal with whom readers reluctantly identify themselves. Although Nast has placed the sexton's shovel and lantern in prominent positions, he has eliminated such details as the skull and the wicker bottle. To emphasize Grub's age, Nast has removed Grub's hat to reveal his balding pate, but has maintained his posture: he he rises from his seat, he seems transfixed by the horrible sight. However, in creating his curmudgeonly sexton, Nast has eschewed any kind of naturalism as he has rendered the aptyly-named Gabriel Grub rigidly paralyzed and utterly terrified. Nast renders the antagonist, the Goblin King, laughable rather than terrifying as he smacks more of a children's Hallowe'en party or pantomime than of a gothic tale. Whereas Phiz has watered down the impact of the supercilious supernatural visitor by offering nine miniature iterations of his round head and wide-brimmed, sugar-loaf hat, Nast at least takes the one-on-one encounter seriously enough for the reader to recognize such textual components as the enormous tombstone, the long, fantastic legs, and antiquated costume of the goblin in a far less cluttered composition. What Nast has added that Phiz, used to damp English Christmasses, has not thought to include is frost and snow.

Phiz's plates for "Goblin Who Stole a Sexton" in the 1836-37 and 1874 Editions

Above: In the 1874 Household Edition of the novel Phiz has modelled his illustration on his own January 1837 engraving: "Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange unearthly figure". [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Related Materials: Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-68

- The Nine Interpolated Tales in Pickwick

- Interpolated Tales in Dickens's Pickwick Papers

- A Comprehensive List of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-1868

- An Overview of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-1868

- A Critical Analysis of Dickens's Short Fiction, 1833-68

- Dickens' Aesthetic of the Short Story

- The Victorian Short Story: A Brief History

The Other Christmas Scenes from Nast's Sequence set at Manor Farm, Dingley Dell

- Frontispiece, "Went slowly and gravely down the slide with his feet about a yard and a quarter apart."

- Mr. Pickwick. Second Frontispiece.

- "It was a pleasant thing to see Mr. Pickwick in the centre of the group. [Pickwick under the mistletoe]

- "I wish you'd let me bleed you."

- A large mass of ice disappeared.

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-74

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Hablot Knight Brown (1836-37)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Hablot Knight Browne (1874)

- A selected list of illustrations by Harry Furniss for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustration for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Related Material

- Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (homepage)

- Nast’s Pickwick illustrations

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- The complete list of illustrations by Phiz for the Household Edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour and Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman & Hall, 1836-37.

__________. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, Edited by Boz. Philadelphia: Carey, Lea, and Blanchard, 1836. 5 vols.

__________. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. New York: Harper and Brothers 1873.

__________. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Volume 2.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 2: "Imaginative Overindulgence." Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982. Pp. 7-31.

Last modified 15 December 2019