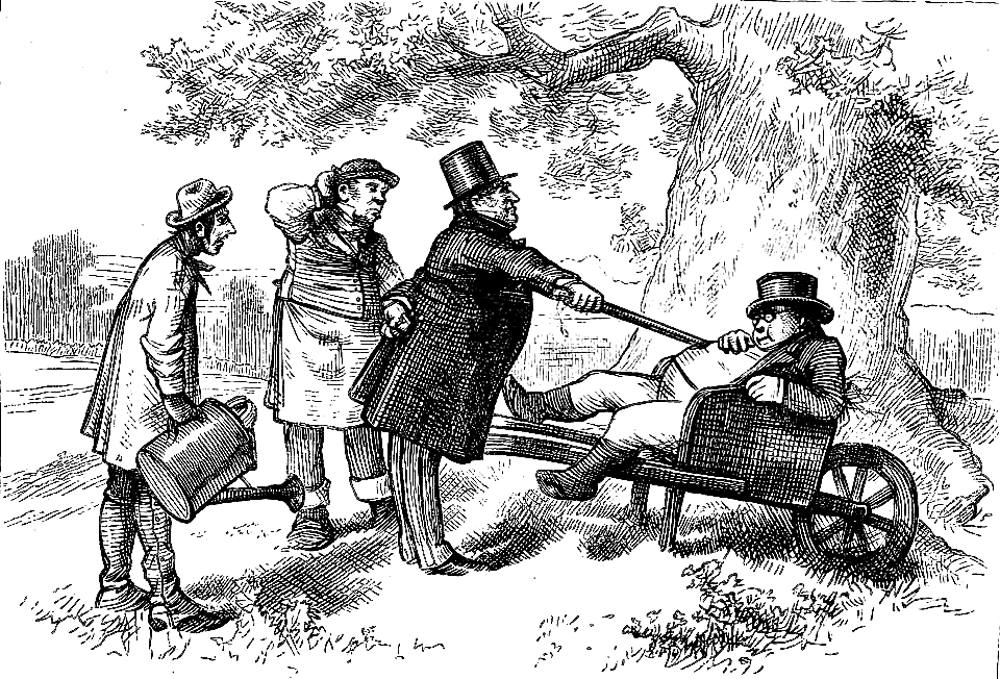

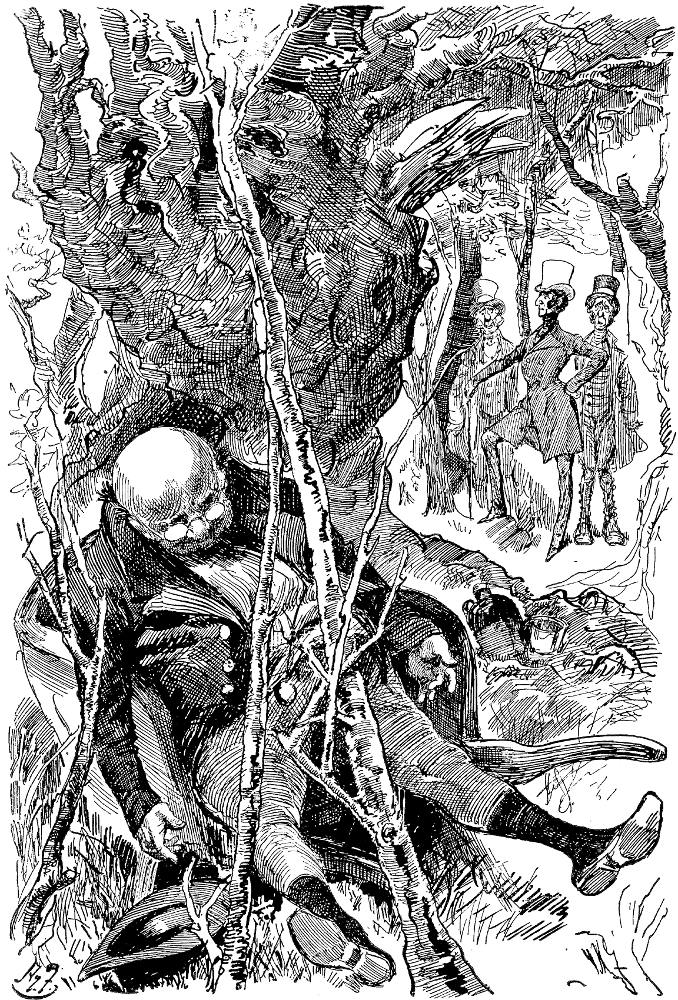

"Who are you, you rascal?" by Thomas Nast, in Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club, Chapter XIX, p. 117. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Bibliographical Note

The illustration appears in the American Edition of Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club, Chapter XIX, "A Pleasant Day with an Unpleasant Termination," p. 117. Wood-engraving, 3 5⁄8 inches high by 5 ¼ inches wide (9.2 cm high by 13.3 cm wide), framed, half-page; referencing text on the previous page; descriptive headline: "Captain Boldwig in a Passion" (p. 117). New York: Harper & Bros., Franklin Square, 1873.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Narrative Context of the Illustration: Boldwig discovers Pickwick drunk

"I beg your pardon, sir," said the other man, advancing, with his hand to his hat.

"Well, Wilkins, what's the matter with you?" said Captain Boldwig.

"I beg your pardon, sir — but I think there have been trespassers here to-day."

"Ha!" said the captain, scowling around him.

"Yes, sir — they have been dining here, I think, sir."

"Why, damn their audacity, so they have," said Captain Boldwig, as the crumbs and fragments that were strewn upon the grass met his eye. "They have actually been devouring their food here. I wish I had the vagabonds here!" said the captain, clenching the thick stick.

"I wish I had the vagabonds here," said the captain wrathfully.

"Beg your pardon, sir," said Wilkins, "but —"

"But what? Eh?" roared the captain; and following the timid glance of Wilkins, his eyes encountered the wheel-barrow and Mr. Pickwick.

"Who are you, you rascal?" said the captain, administering several pokes to Mr. Pickwick's body with the thick stick. "What's your name?"

"Cold punch," murmured Mr. Pickwick, as he sank to sleep again.

"What?" demanded Captain Boldwig.

No reply.

"What did he say his name was?" asked the captain.

"Punch, I think, sir," replied Wilkins. [Chapter XIX, "A Pleasant Day with an Unpleasant Termination," the Chapman & Hall Household Edition, p. 130; the Harper & Bros. Household Edition, p. 117]

Commentary: A Fresh Response to Pickwick in the Pound

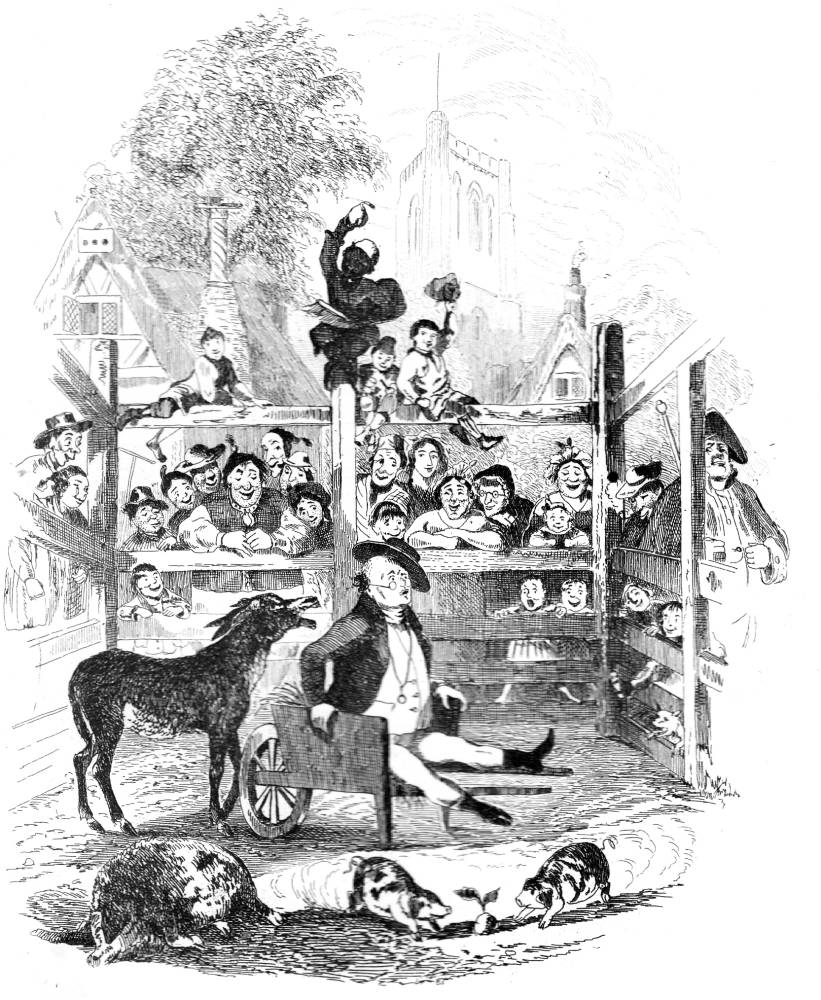

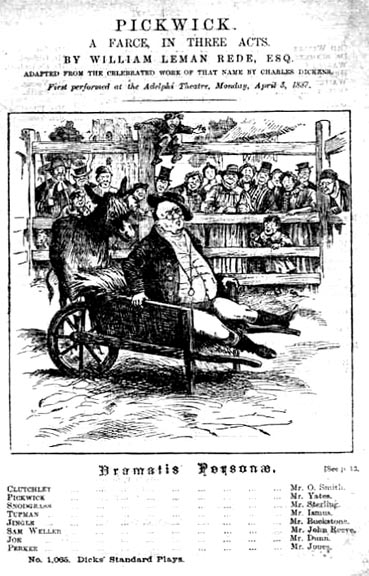

Left: Phiz's original serial illustration Pickwick in the Pound (October 1836). Right: An adaptation of Phiz's original serial illustration Pickwick in the Pound (October 1836) for the cover and title-page of Dicks' Standard Play 1065.

Curiously, in preparing his series of fifty-seven woodcuts for the 1874 edition Phiz elected not to redraft this highly effective engraving, and he chose instead to depict the scene in which the irate landowner, Captain Boldwig, has the comatose Pickwick impounded for trespass. Robert Patten has noted that the donkey and swine may point to a biblical interpretation, although he does not note that swine were the companions of the Prodigal Son in the Christian parable:

Mr. Pickwick comes to the pound through his own follies: the folly of being out on a rainy night, hiding in a private garden to prevent the elopement of a stranger; the folly of watching a shooting expedition from a wheelbarrow; the folly of consuming too much veal pie and imbibing too much cold punch. For correction, he is isolated from his fellow Pickwickians, and divided from the villagers by the wooden fence of the pound. [Robert L. Patten, "Boz, Phiz and Pickwick in the Pound," 580]

In the sixteenth plate for the original serialisation of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (October 1836), irate magistrate Captain Boldwig has apprehended the comatose Pickwick, who is apparently still feeling the effects of multiple glasses of cold punch. Boldwig has ordered the trespasser transported as a "drunken plebeian" in the wheelbarrow from the scene of his "debauch" (a picnic, in fact) on Captain Boldwig's land at One-tree Hill (the very name suggestive of the hanging of criminals, if not of Christian redemption through suffering) to the local impound for stray animals. The 1836 steel-engraving, in turn, became the basis within a year for the cover of Dicks' Standard Play 1065 and the title-page of Pickwick. A Farce, In Three Acts, William Lehman Rede's dramatic adaptation of Dickens's incomplete novel. The play was first performed at London's Adelphi Theatre, on 3 April 1837 — although the serial did not arrive at its final instalment until the November 1837 double number.

In 1873, Nast and Phiz apparently worked independently, separated as they were by the North Atlantic. Nast may also have seen some proofs sent over from London, even though Chapman and Hall held back publication of their Pickwick until 1874. Whatever the circumstances, both illustrators have selected precisely the same moment in Chapter 19 for realisation. The pompous Boldwig enjoys his petty authority and the deference he receives from gardeners and gamekeepers; but here, despite his enebriation, is a very different sort of interloper than the usual vagabonds and poachers — by his clothing the supposed sot in the wheelbarrow is a townsman and respectable bourgeois. Both artists create this comic scene that contrasts the rage of the rural official and the passivity of the urban transgressor. In neither illustration does the under-gardener, Wilkins (identified by his linen smock-frock and enormous watering-can in the Nast illustration), have his hand to his hat in deference to the majestic Boldwig's supercilious and arbitrary authority, so well exemplified by his cane.

Phiz, a classically trained artist, might have perceived the correspondence between Boldwig's prodding Pickwick with his cane here and the angelic guards of Eden prodding the disguised Satan with their spears in Milton's Paradise Lost.

Him thus intent Ithuriel with his Spear Touch'd lightly; for no falshood can endure Touch of Celestial temper, but returns Of force to its own likeness . . . [Book IV, lines 810-13]

But the snoring Pickwick is neither a malevolent interloper nor an incarnation of evil (despite Boldwig's misapprehension of him), and the retired military officer is hardly equivalent to the angelic guardian of Eden — just another petty official trying to put down trespassing. Trespassers and committers of public nuisances quickly find themselves in the pound under Boldwig's administration as if they are errant donkeys. Nast communicates Boldwig's officiousness through his stiff posture, and through contrasting him with the unemotional curiosity of Hunt, the gardener (holding the watering-can) and Wilkins, the sub-gardener. Nast has both realised Boldwig's confronting the drunken Pickwick and also effectively communicated Dickens's introduction of him: "Captain Boldwig was a little fierce man in a stiff black neckerchief and blue surtout . . . with a thick rattan cane with a brass ferule" (116), although the artist has increased the angry landowner's bulk.

Indignant at the tell-tale evidence of picnicking and trespass on his property, Boldwig orders his men to transport the "plebeian," in a drunken stupor in the wheelbarrow in which the trio have discovered him, and deposit him in the village pound, which serves as a jail for the village. Pickwick does not answer Boldwig, merely giving his name as "Cold Punch." Of the two gardeners in Phiz's picture, we may assume that Wilkins is immediately behind the pompous Boldwig, and that the man with the trowel is Hunt. Similarly, Nast uses two cartoonist's tricks to establish the identities of the gardeners, for the "sub-gardener," Wilkins, is a thin, smockfrock-wearing peasant carrying an oversized watering can, while his superior, Hunt, a stouter individual, is nearer Boldwig and wears more conventionally middle-class attire: an apron, a vest, and a shirt. The less intelligent Wilkins gapes, open-mouthed, at the trespasser, whereas Hunt scratches his head, not sure what to make of a respectably clad, elderly, middle-class gentleman in such a pose and embarrassing situation. The object, however, that establishes which of the two is Wilkins is somewhat improbable since the object of Boldwig's inspection is not to water potted plants. Nor is Nast's Boldwig particularly well realised as in the text the haughty landowner is "a little fierce man in a stiff black neckerchief and blue surtout . . . with a thick rattan stick" (Harper & Brothers, p. 116; Champan & Hall, p. 129).

Whereas Nast captures the Captain's bellicose nature and military bearing, Phiz more ably conveys through his coloured face, facial hair, and rotund figure something of Boldwig's pomposity. Moreover, Phiz's gardeners, who surround Pickwick rather than, as in Nast's woodcut, observe him, are humorous and engaging characters whose aprons and implements (the broom and the trowel) bespeak their occupation. The chief difference between the two compositions, however, is the central placement of the addled Pickwick in Phiz's, and Nast's central placement of Boldwig, thrusting his cane into the trespasser rather than gently prodding the drunkard. Nast employs the juxtaposition of the sleeping inebriate and the noble, aged oak above him to emphasise Pickwick's figure, and perhaps obliquely comment on the inappropriateness of a revered elder finding himself in such a compromised position through the immoderate consumption of an alcoholic beverage. Phiz has Pickwick semiconscious but unable to rise, his hat (the sign of his middle-class respectability) abandoned on the ground, whereas the much chubbier Pickwick of Nast's woodcut is still fast asleep, his hat still firmly planted on his head. If, as Sergeant Buzfuz in his courtroom peroration about Pickwick's character asserts, Pickwick is metaphorically a "serpent," that is, an interloper and deceiver, he has unwittingly enacted the role of the serpent in Eden in this plate, prodded not by the spear of the angel-warrior Gabriel as in Book Four of Paradise Lost, but by the rattan cane of the class-conscious, ex-military man Captain Boldwig, who is as brazen as his ferule.

This, one of the most popular images of Pickwick, does not show him at his best, and perhaps that was the reason for its popularity: it shows the somewhat stuffy, slightly self-righteous retired businessman and amateur scientist taken down a peg when a petty local official mistakenly takes the respectable bourgeois for a drunken trespasser.

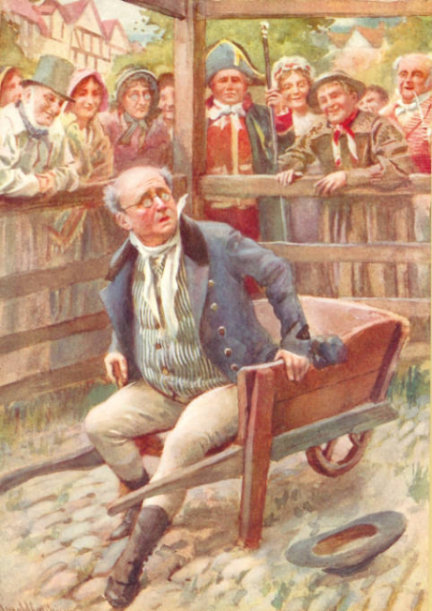

Left: Harold Copping's version of the original serial illustration, with Pickwick stunned, disoriented, and pathetic — an aged bourgeois held up to ridicule: Mr. Pickwick in the Pound (1924) for Character Sketches from Dickens. Right: Harry Furniss's re-thinking of the Household Edition illustration: The Effect of Cold Punch after the Shooting Party (1910) for the Charles Dickens Library Edition.

Another approach: Phiz's depiction of Pickwick, passed out in the wheelbarrow, in the British Household Edition (1874)

Phiz's approach to this episode in the novel is completely consistent with his original plate: "Who are you, you rascal?" said the captain, administering several pokes to Mr. Pickwick's body with the thick stick. "What's your name?", page 129, Chapter XIX; preface to "Pickwick in the Pound."

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-1910

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Hablot Knight Brown (1836-37)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Hablot Knight Browne (1874)

- A selected list of illustrations by Harry Furniss for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustration for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Related Material

- Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (homepage)

- Nast’s Pickwick illustrations

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- The complete list of illustrations by Phiz for the Household Edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. "Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Robert Seymour and Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman & Hall, 1836-37.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. New York: Harper and Brothers 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

Last modified 3 December 2019