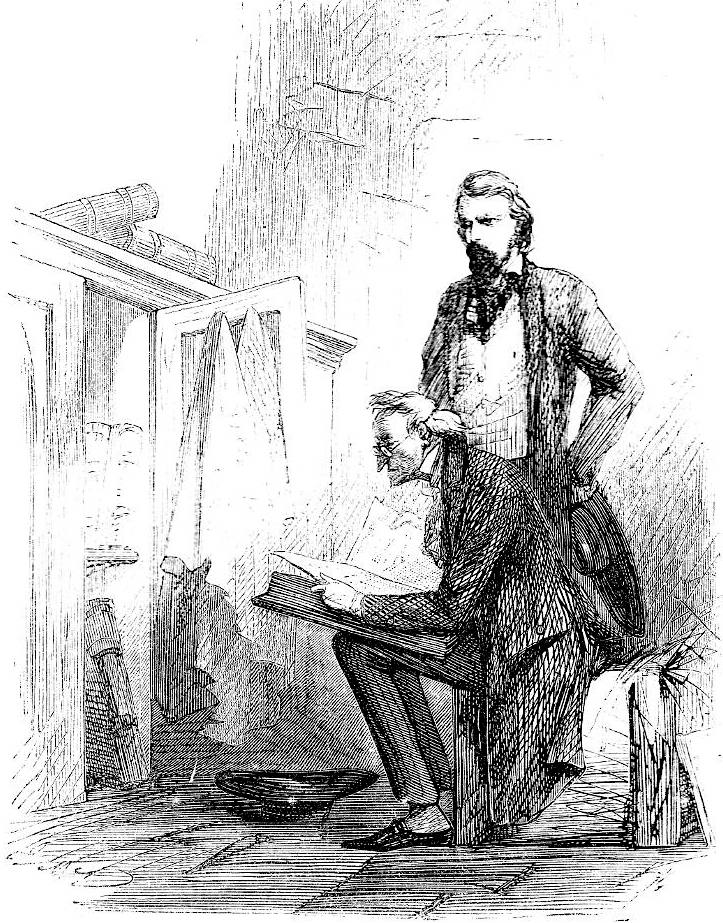

"What year did you say, Sir?"

John McLenan

7 July 1860

11.4 cm high by 8.8 cm wide (4 ¼ by 3 ½ inches), vignetted, p. 421; p. 209 in the 1861 volume.

Thirty-third regular illustration for Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (1860).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.