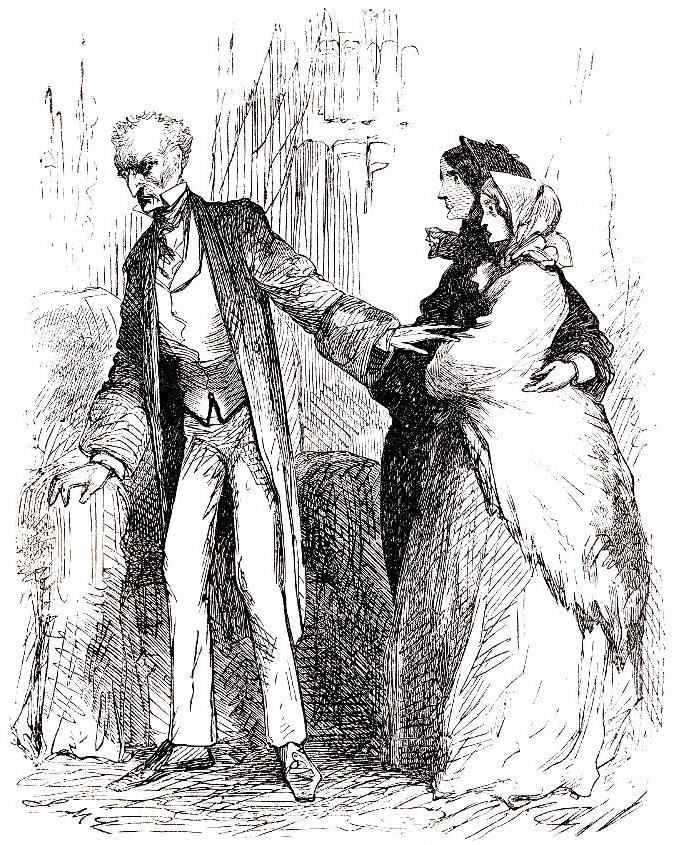

"Mr. Fairlie declared in the most positive terms that he did not recognize the woman."

John McLenan

2 June 1860

11.2 cm high by 8.8 cm wide (4 ¼ by 3 ½ inches), vignetted, p. 341; p. 179 in the 1861 volume.

Twenty-sixth regular illustration for Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (1860).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.