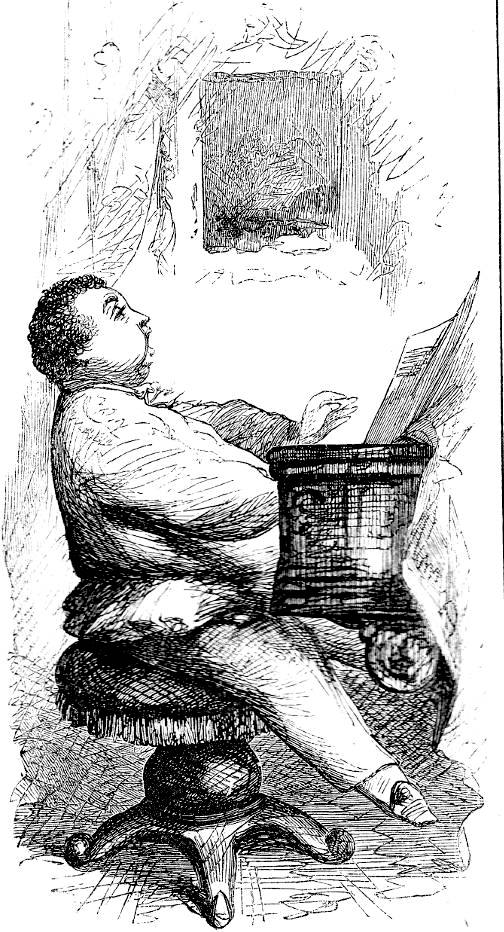

Count Fosco plays Italian music on the piano

John McLenan

7 April 1860

10.6 cm high by 5.6 cm wide (4 by 2 ¼ inchess), vignetted.

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for the twentieth weekly number of Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (7 April 1860), 213; p. 132 in the 1861 volume.

[Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The illustration intensifies the reader's concerns about the role that the Foscos are playing in Glyde's plans to alienate and control his wife as he has just discharged the faithful lady's maid, Fanny, and made sure that his wife and Marian are under the constant surveillance of the Foscos, whether in- or out-of-doors.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.