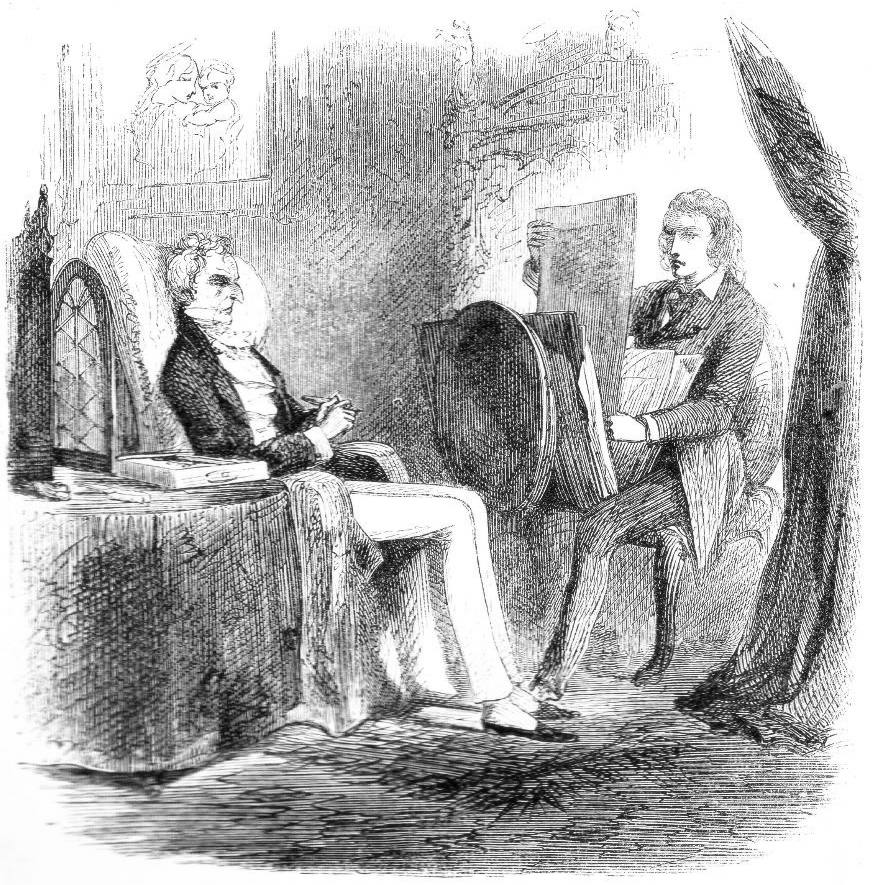

"My taste was sufficiently educated to enable me to appreciate the value of the drawings while I turned them over."

John McLenan

3 December 1859

4 ⅝ by 4 ½ inches (11.9 cm by 11.7 cm), vignetted.

Second full-size for Collins's The Woman in White: A Novel (1861), p. 19.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.