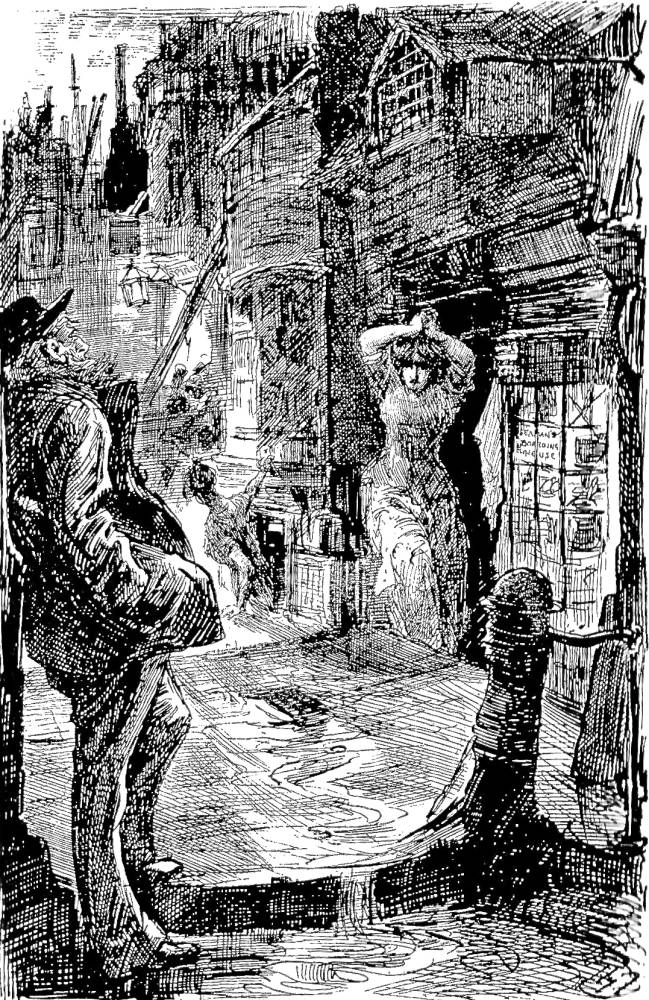

"Yet the cold was merciful, for it was the cold night air and the rain that restored me from a swoon on the stones of the causeway" (p. 160) — James Mahoney's twenty-eighth illustration for Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Household Edition (New York), 1875. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.1 cm high x 13.3 cm wide. The Harper and Brothers woodcut for thirteenth chapter, "A Solo and a Duet," in the second book, "Birds of a Feather," realizes the moment in John Harmon's interior narrative flashback when, having been drugged or poisoned and dumped into the Thames, he regains consciousness and crawls ashore. Having visited Rogue and Pleasant Riderhood at Limehouse Hole disguised as a merchant sailor, Harmon begins to recognize his surroundings and reconstruct his experiences on that fateful night. The young sailor (who so much resembled him) whom he took into his confidence on the return voyage to England, George Radfoot, had conspired with Riderhood to poison Harmon and steal his belongings. After Harmon emerges from the water, he decides to assume a new identity: "John Rokesmith." Such disguises and blending of upper-middle-class and low life, of murder and intrigue and deception, are characteristics of the new subgenre of the period, the Sensation Novel, initiated by Wilkie Collins with The Woman in White (1860). In an odd twist on the usual detective story plot, the murdered man is playing detective to uncover the circumstances surrounding his own murder. Here, the victim of the crime plays detective to determine the relative guilt of the various participants as he has just leveraged what evidence he has against Riderhood to compel the dishonest waterman to exonerate Gaffer Hexam. In this model of the Darwinian struggle for survival, the individual comes up from the water to shed his former identity and adopt a new one — and perhaps become a more evolved being spiritually and psychologically.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

"It was only after a downward slide through something like a tube, and then a great noise and a sparkling and crackling as of fires, that the consciousness came upon me, 'This is John Harmon drowning! John Harmon, struggle for your life. John Harmon, call on Heaven and save yourself!' I think I cried it out aloud in a great agony, and then a heavy horrid unintelligible something vanished, and it was I who was struggling there alone in the water.

"I was very weak and faint, frightfully oppressed with drowsiness, and driving fast with the tide. Looking over the black water, I saw the lights racing past me on the two banks of the river, as if they were eager to be gone and leave me dying in the dark. The tide was running down, but I knew nothing of up or down then. When, guiding myself safely with Heaven's assistance before the fierce set of the water, I at last caught at a boat moored, one of a tier of boats at a causeway, I was sucked under her, and came up, only just alive, on the other side.

"Was I long in the water? Long enough to be chilled to the heart, but I don't know how long. Yet the cold was merciful, for it was the cold night air and the rain that restored me from a swoon on the stones of the causeway. They naturally supposed me to have toppled in, drunk, when I crept to the public-house it belonged to; for I had no notion where I was, and could not articulate — through the poison that had made me insensible having affected my speech — and I supposed the night to be the previous night, as it was still dark and raining. But I had lost twenty-four hours. &mdash, "Chapter 13: A Solo and a Duet," p. 160.

Commentary

Despite the fact that it was his visual antecedent, Mahoney's 1875 treatment of the resurrection scene is more realistic and less impressionistic than that by Dickens's original serial and volume illustrator Marcus Stone, in More Dead than Alive, the second illustration for the January, 1865, the ninth monthly part in the British serialisation. And, although they had access to the Stone series, American illustrators Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867) and Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1866) chose to depict earlier scenes at Limehouse Hole and did not focus on John Harmon's interior narrative. Thus, one should examine the 1875 composite wood-engraving by James Mahoney only in terms of the dark plate that served as his model for his owndark plate with vigorous cross-hatching and fine diagonally ruled lines in imitation of driving rain from upper left to lower right, as if penetrating the struggling victim of conspiracy.

Although Percy Muir contends that dark plates, whether on copper, steel, or boxwood, are never wholly successful because they are striving to attain an effect that only a mezzotint can achieve, both Stone and Mahoney use such an illustration toconveying a sense of the horrible, near-death experience that Harmonre-lives after exiting the Riderhoods' leaving-shop.

A great deal has been made of the so-called dark plates in these books [i. e., Bleak House, Little Dorrit, and A Tale of Two Cities]. The fact is that they were neither entirely new nor entirely successful. What Browne ['Phiz'] tried to do with the dark plates was to produce the effect of mezzotinting on an etched plate. It is usually a mistake to attempt to imitate one medium in a different technique and this was no exception to the rule. The effect was produced by having a background of fine, closely spaced lines mechanically ruled all over the plates, and then, by elaborate methods of burnishing the high-lights and stopping out the shadows, to increase the contrasts. The result when seen at its best, as in 'On The Dark Road' in Dombey, is not ineffective, but at its worst, as in 'The Mourning' [sic] in Bleak House, is a rather nasty mess. [96]

Although Muir dismisses Stone's series as "totally undistinguished" (96) and does not consider the Household Edition illustrations, More Dead than Alive is one of Stone's most psychologically penetrating realisations of Dickens's text, as the murkiness of the scene, suggestive to modern reader of Film Noir, brilliantly reduces the figure of the protagonist to the bare essentials in his struggle to cling to life. Stone offers the reader his construction of the emotional content of Harmon's fragmentary recollection of crawling, soaking wet, across planking (hardly a"causeway") towards the shore, as the driving rain, reiterated in the text as thedominating feature of the fateful night, largely obscures the backdrop; whereasDickens specifically mentions a moored boat nearby, Stone gives us only pylons,rendering the whole scene bleak and inhospitable. The illustration is strongly impressionistic, not realising the text so much as using it as a point of departure, putting the reader through the protagonist's near-death experience by engulfing the reader in the pelting rain and darkness, Harmon's body almost a wet sack rather than recognizable as a human form, in contrast to Mahoney's clearly apprehended figure.

Mahoney's re-interpretation of the same illustration to realise the same textual moment includes a clearlyseen foreground, with Harmon, the causeway (at best, a ruined boat-ramp), and a derelict anchor that reinforces the victim's gripping the rocks with his right handas he blindly gropes for a further hold with his left. In the middle-ground, notquite as sharp, is the Thames-side public house into which Harmon will eventuallystumble. Then, in imitation of the out-of-focus backgrounds of early photographs,Mahoney has sketched in an indistinct pair of boat prows, London Bridge, andwarehouses. The eye begins with the pathetic figure, is drawn towards the public-house (right), then moves into the murky distance, across the bridge to the boats, and thence back to the prostrate figure. Whereas Stone achieved his desired effect through indistinctness, underscoring the bone-chilling rain that represents nature's relentless powers of destruction, Mahoney conveys a sure sense of Harmon's determined, Darwinian struggle, intensifying the reader's identification with the protagonist.

Rokesmith disguised as a sailor in the original and later editions, 1865-1910

Left: Marcus Stone's January 1865 serial illustration of Harmon's emerging from the Thames, barely alive, More Dead than Alive. Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's dual character study of the Riderhoods, as they were before the visit of Harmon-Rokesmith in disguise, Rogue Riderhood and Miss Pleasant at Home (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Left: F. O. C. Darley's version of Rokesmith'sinterviewing Rogue Riderhood in the Limehouse Hole "leaving shop," Riderhood Checkmated (1866). Right: Harry Furniss's impressionistic treatment of Rokesmith's observing Rogue Riderhood's business from a vantage point across the street, Outside the seamen's boarding-house (Charles Dickens Library Edition, 1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Illustrated Household Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Field; Lee and Shepard; New York: Charles T. Dillingham, 1870 [first published in The Diamond Edition, 1867].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall' New York: Harper & Bros., 1875.

Grass, Sean. Charles Dickens's 'Our Mutual Friend': A Publishing History. Burlington, VT, and Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The CharlesDickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp.441-442.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. (1899). Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Muir, Percy. Victorian Illustrated Books. London: B. T. Batsford, 1971.

"Our Mutual Friend — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Queen's University, Belfast. "Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Clarendon Edition. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864-December 1865." Accessed 12 November 2105. http://www.qub.ac.uk/our-mutual-friend/witnesses/Harpers/Harpers.htm

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 19December 2015