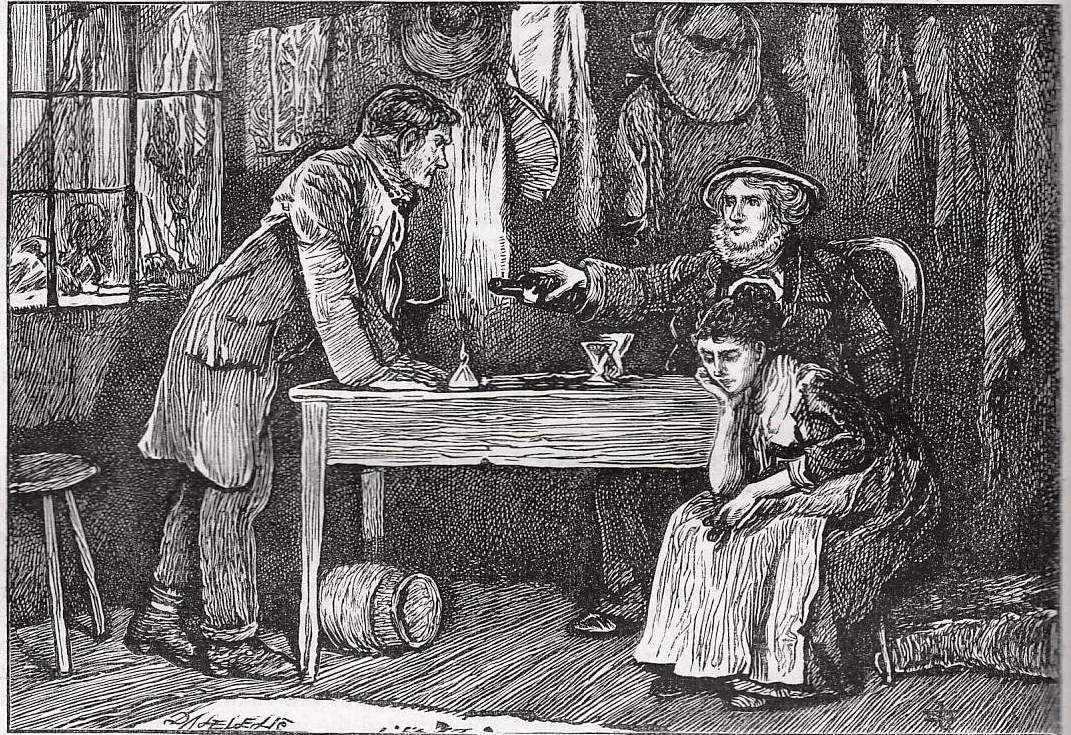

And now, as the man held out the bottle to fill all round, Riderhood stood up, leaned over the table to look closer at the knife, and stared from it to him. (p. 155). James Mahoney's twenty-seventh illustration for Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Household Edition (New York), 1875. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 9.3 cm high x 13.4 cm wide. The Harper and Brothers woodcut for twelfth chapter, "More Birds of Prey," in the second book, "Birds of a Feather," concerns the visit of the mysterious sailor to the rooming-house and pawn shop run by Pleasant Riderhood and her father, the Thames waterman of scurrilous character, Rogue, at Limehouse Hole, east of the metropolis. Coolly, the bearded stranger who refuses to give his name accuses Rogue of having lied to the authorities about Gaffer Hexam's role in the murder of John Harmon, recently returned from the east. Using intimidation and innuendo, the sailor compels Rogue Riderhood to agree to sign an affidavit attesting to Gaffer's innocence. Who is this sailor who seems to have murdered Rogue's confederate, George Radfoot, and is now threatening Pleasant? Afterwards, in the street, the stranger removes his disguise to reveal himself as none other than the mild-mannered private secretary John Rokesmith. Such disguises and blending of upper-middle-class and low life, of murder and intrigue and deception, are characteristics of the new subgenre of the period, the Sensation Novel, initiated by Wilkie Collins with The Woman in White (1860).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

And now, as the man held out the bottle to fill all round, Riderhood stood up, leaned over the table to look closer at the knife and stared from it to him.

"Wat's the matter?" asked the man.

Why, I know that knife!" said Riderhood.

"Yes, I dare say you do."

He motioned to him to hold up his glass, and filled it. Riderhood emptied it to the last drop and began again.

"That there knife —"

"Stop," said the man, composedly. "I was going to drink to your daughter. Your health, Miss Riderhood."

"That knife was the knife of a seaman named George Radfoot."

"It was."

"That seaman was well beknown to me."

"He was."

"What's come to him?"

"Death has come to him. Death came to him in an ugly shape. He looked," said the man, "very horrible after it."

"Arter what?' said Riderhood, with a frowning stare.

"After he was killed."

"Killed? Who killed him?"

Only answering with a shrug, the man filled the footless glass, and Riderhood emptied it: looking amazedly from his daughter to his visitor.

Commentary

Despite the fact that it was his visual antecedent, Mahoney's 1875 treatment of the trio and setting of the scene does not much resemble that of Marcus Stone, Dickens's original serial and volume illustrator, in Miss Riderhood at Home, the first illustration for the January, 1865, the ninth monthly part in the British serialisation. And whereas American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Jr. in the 1867 Diamond Edition sequence chose to depict the stormy relationship between Pleasant and her abusive father in Rogue Riderhood and Miss Pleasant at Home, James Mahoney has elected to avoid mere characterisation in favour of capturing the Riderhoods in the midst of their confrontation with the disguised Rokesmith. Although his style and treatment are not as elegant as the photogravure frontispiece by Felix Octavius Carr Darley, Riderhood Checkmated in 1866, the Mahoney illustration of the next decade achieves a certain verisimilitude in the crazed window, battered table, and assorted clothing hanging behind the trio; moreover, Mahoney (unlike Darley) realised that Rogue should not be wearing the clothing of a merchant-seaman. The moment Stone realizes is somewhat earlier, for Rogue has not yet arrived home, whereas Mahoney has chosen the moment when tensions between the two men are about to reached the breaking point that Darley depicted, leaving the reader to wonder how Riderhood will react to seeing his friend's knife in another's hands.

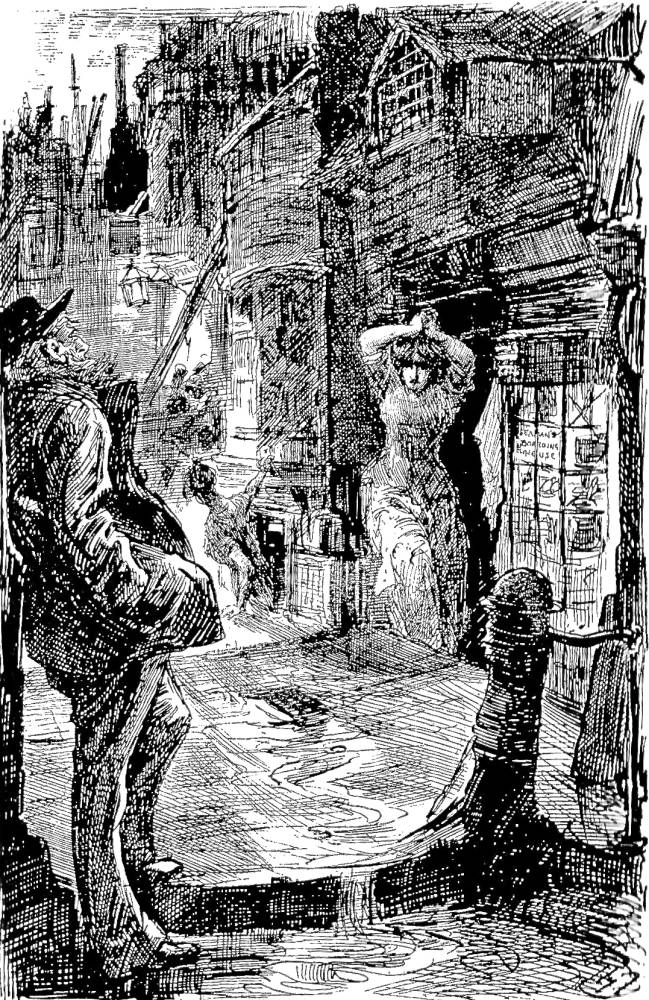

The scene in other illustrators' interpretations except Harry Furniss's is also within the kitchen-parlour-and-pawnbroker's shop of Pleasant Riderhood's lodging house in Limehouse. The clothing hanging in the background (not evident in the front window of the shop in the Furniss illustration) are items of apparel pawned by sailors down on their luck. While Rogue Riderhood, a waterman who scavenges the Thames, has been momentarily out of the shop, John Harmon (that is to say, the supposedly murdered "John Rokesmith," disguised as a sailor) subsequent to the Furniss illustration strikes up a conversation with the proprietess and begins to question her. As in the original monthly part illustration (January 1865) by Marcus Stone, in the 1866 interpretation by Felix Octavius Carr Darley, she is still endeavouring to put up her hair — evidently in preparation for ironing. The bearded stranger seen lounging across the street in the Furniss illustration in these other illustrations has entered the business and is interrogating either Pleasant (in Miss Riderhood at Home, for instance) or her father, as in Darley's Riderhood Checkmated. In an odd twist on the usual detective story plot, the murdered man is playing detective to uncover the circumstances surrounding the murder; here, he is leveraging what evidence he has against Riderhood to compel the dishonest waterman to exonerate his fellow waterman, Gaffer Hexam, of any implication that he murdered a recently arrived passenger whose body was found in Thames.

The meaning of situation in the Mahoney illustration should be apparent to any reader of this volume of The Household Edition since the illustrator has provided an ample caption and reader will have encountered the passage realised on the very same page (155). Moreover, a simultaneous reading of illustration and text encourages the reader to check details in the illustration against the text. What is happening is reasonably clear: John Rokesmith, disguised with a beard and wearing the peacoat of a merchant-seaman, is casually extending the bottle of spirits (one might assume rum) across the table in order to pour his interlocutor a measure; however, exactly as in the text, Riderhood has suddenly turned his glass "upside down upon the table" (155). Pleasant, little interested, is shown "occupying a stool between the latter [Rokesmith] and the fireside" (154) as suggested by the hearthstone beside her feet, and Riderhood has taken the glass without a foot — all of which details indicate that Mahoney has read the passage with great care. The focus of the illustration, however, is not the disguised Rokesmith, but the cunning Riderhood, who strongly suspects his visitor as harbouring less than congenial intentions.

In contrast to the subtlety of Darley's engraving, Mahoney utlises the bold lines of the composite wood-engraving medium to establish a sinister mood — in Furniss's illustration, the dark lines establish the baleful atmosphere of The Hole, Limehouse. As both J. A. Hammerton and Frederic G. Kitton have noted, the original illustration by Marcus Stone, who worked closely with Dickens, bears the stamp of authorial intention, influencing later illustrators as an adjunct to the original text. Conversations with and detailed notes from the novelist gave young Stone direct access to what he himself termed Dickens's "pictorialism" (Kitton, 197), that is, an innate sense of what in in a text will be most suitable as an illustration. However, Mahoney seems to have reacted against Stone's Miss Riderhood at Home by dramatising a moment of danger.

As opposed to the static illustrations of Stone and Furniss, those of Eytinge, Darley, and Mahoney capture the characters in the midst of action, a moment of tableau, with the volatile Riderhood as the most active figure in the scene. In the Eytinge engraving, Riderhood holds aloft a boot and is about to strike his daughter; in Mahoney, he is suddenly alerted to the danger that the stranger may pose; and in Darley's photogravure, Riderhood, rises suddenly, when accused of lying to the lawyer about the murder, "as though he would fling his glass in the man's face" when the stranger calls him a liar. Rokesmith in Mahoney's illustration projects an impression of calm self-control, as if he has already calculated what Riderhood's response will be.

Rokesmith disguised in the original and later editions, 1865-1875

Left: Marcus Stone's January 1865 serial illustration of Rokesmith's visit to the Riderhoods' shop and rooming-house, Miss Riderhood at Home. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's dual character study of the Riderhoods, Rogue Riderhood and Miss Pleasant at Home (1867). Right: F. O. C. Darley's version of Rokesmith's interviewing Rogue Riderhood in the "leaving shop," Riderhood Checkmated (1866). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Harry Furniss's impressionistic treatment of Rokesmith's observing Rogue Riderhood's business from a vantage point across the street, Outside the seamen's boarding-house (Charles Dickens Library Edition, 1910). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Illustrated Household Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Field; Lee and Shepard; New York: Charles T. Dillingham, 1870 [first published in The Diamond Edition, 1867].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall' New York: Harper & Bros., 1875.

Grass, Sean. Charles Dickens's 'Our Mutual Friend': A Publishing History. Burlington, VT, and Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The CharlesDickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp.441-442.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. (1899). Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Our Mutual Friend — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Queen's University, Belfast. "Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Clarendon Edition. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864-December 1865." Accessed 12 November 2105. http://www.qub.ac.uk/our-mutual-friend/witnesses/Harpers/Harpers.htm

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 19 November 2015