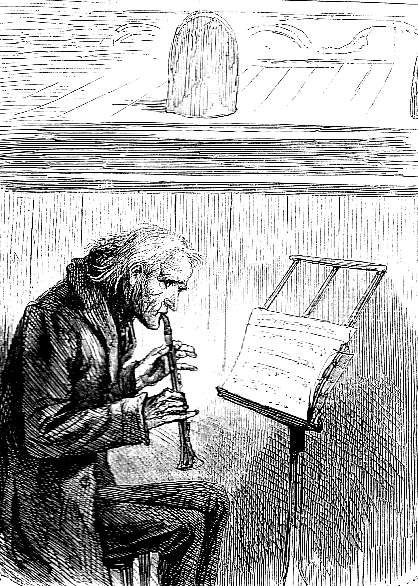

The two brothers were before their Father; — Page 334, in Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 19, "The Storming of the Castle in the Air," opposite page 334, Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's forty-seventh illustration (and the final of the volume's four, full-page composite wood-engravings) for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 13.2 cm high x 17.1 cm wide. The Chapman and Hall woodcut is identical to that in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition, but the caption for this plate in the Harper and Bros. volume (for which it serves as the frontispiece) is somewhat lengthier: One figure reposed upon the bed, the other kneeling on the floor, drooped over it the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet; . . . the two brothers were before their Father; far beyond the twilight judgments of this world; high above its mists and obscurities — Book 2, chap. xix..

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

At first her uncle was stark distracted. "O my brother! O William, William! You to go before me; you to go alone; you to go, and I to remain! You, so far superior, so distinguished, so noble; I, a poor useless creature fit for nothing, and whom no one would have missed!"

It did her, for the time, the good of having him to think of and to succour.

"Uncle, dear uncle, spare yourself, spare me!"

The old man was not deaf to the last words. When he did begin to restrain himself, it was that he might spare her. He had no care for himself; but, with all the remaining power of the honest heart, stunned so long and now awaking to be broken, he honoured and blessed her.

"O God," he cried, before they left the room, with his wrinkled hands clasped over her. "Thou seest this daughter of my dear dead brother! All that I have looked upon, with my half-blind and sinful eyes, Thou hast discerned clearly, brightly. Not a hair of her head shall be harmed before Thee. Thou wilt uphold her here to her last hour. And I know Thou wilt reward her hereafter!"

They remained in a dim room near, until it was almost midnight, quiet and sad together. At times his grief would seek relief in a burst like that in which it had found its earliest expression; but, besides that his little strength would soon have been unequal to such strains, he never failed to recall her words, and to reproach himself and calm himself. The only utterance with which he indulged his sorrow, was the frequent exclamation that his brother was gone, alone; that they had been together in the outset of their lives, that they had fallen into misfortune together, that they had kept together through their many years of poverty, that they had remained together to that day; and that his brother was gone alone, alone!

They parted, heavy and sorrowful. She would not consent to leave him anywhere but in his own room, and she saw him lie down in his clothes upon his bed, and covered him with her own hands. Then she sank upon her own bed, and fell into a deep sleep: the sleep of exhaustion and rest, though not of complete release from a pervading consciousness of affliction. Sleep, good Little Dorrit. Sleep through the night!

It was a moonlight night; but the moon rose late, being long past the full. When it was high in the peaceful firmament, it shone through half-closed lattice blinds into the solemn room where the stumblings and wanderings of a life had so lately ended. Two quiet figures were within the room; two figures, equally still and impassive, equally removed by an untraversable distance from the teeming earth and all that it contains, though soon to lie in it.

One figure reposed upon the bed. The other, kneeling on the floor, drooped over it; the arms easily and peacefully resting on the coverlet; the face bowed down, so that the lips touched the hand over which with its last breath it had bent. The two brothers were before their Father; far beyond the twilight judgment of this world; high above its mists and obscurities. — Book The Second, "Riches," conclusion of Chapter 19, "The Storming of the Castle in the Air," p. 334.

Commentary

Visiting Rome on the nineteenth-century, bourgeois equivalent of the eighteenth-century, aristocratic Grand Tour, William Dorrit, Amy's father, is suddenly unwell, ironically just before he is about to commit the great misstep of proposing to his daughters' governess (the naieve family's companion and instructor), the sententious and dictatorial Mrs. General. At Mr. Merdle's farewell reception, Mr. Dorrit becomes confused, and reverts to his former identity as The Father of the Marshalsea when he delivers a farewell address before Rome's English expatriate community. The present scene of his death after a sharp decline is ten days after the reception. He dies in the family's lavishly furnished rooms, attended by his younger brother Frederick, the musician, who then dies himself. Thus, Mahoney has captured the highly sentimental moment when Frederick (depicted) dies, leaving Little Dorrit a complete orphan. The illustration is so highly effective that Harper and Brothers chose it for the frontispiece in the New York volume.

The Mahoney illustration is a re-interpretation of one of the original serial's illustration, namely Phiz's The Night, the second illustration for the sixteenth monthly number, the first being of the dinner at which Mr. Dorrit experiences a mental collapse (also Book Two, Chapter 19, originally March 1856), An Unexpected After-Dinner Speech. However, whereas Phiz has provided plenty of contextual bric-a-brac to establish the affluence of the English travellers (indeed, these material objects almost seem to entomb the prostrate figure), Mahoney focuses on the somberly dressed, aged upper-middle-class English gentleman who has just followed his older brother into death, freeing them both from a tawdry past and a present obsession with decorous behaviour and the cultivation of polished, sophisticated surfaces.

The Dorrits in the original, American Household, and Diamond Editions, 1857-1867

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's original version of the death of Frederick Dorrit, The Night. Centre: Darley's 1863 frontispiece of the scene in which William Dorrit learns of his providential inheritance, Joyful Tidings (Volume 2). Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's interpretation of the musical younger Brother, Amy's uncle, Frederick Dorrit (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original serial illustration of the banquet in Book 2, Ch. 19, in which William Dorrit suddenly assumes his former person (March 1856). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 15 March 2016