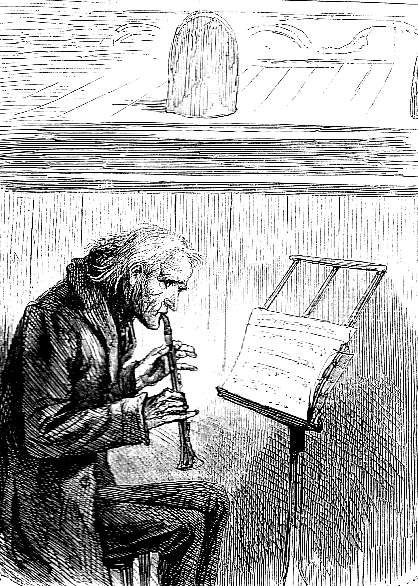

Frederick Dorrit

Sol Eytinge

Wood engraving

10 cm high by 7.4 cm wide (framed)

Eighth full-page illustration for Dickens's Little Dorrit in the James R. Osgood (Boston), 1871, Diamond Edition.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Sol Eytinge, Jr. —> Little Dorrit —> Next]

Frederick Dorrit

Sol Eytinge

Wood engraving

10 cm high by 7.4 cm wide (framed)

Eighth full-page illustration for Dickens's Little Dorrit in the James R. Osgood (Boston), 1871, Diamond Edition.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Frederick Dorrit," the eighth full-page illustration, facing page 137 of the Diamond Edition, by Sol Eytinge, Jr., in Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit (Boston: James R. Osgood [formerly, Ticknor and Fields], 1871).

The eighth illustration, like seventh, presents the study of a single, alienated character, in this case the broken-down clarinet-player Frederick Dorrit, brother of William ("Father of the Marshalsea") and uncle of Edward ("Tip"), Amy, and Fanny. This last niece is a dancer at the small theatre where Frederick is employed. Decidedly a minor character in this expansive novel, William serves primarily to connect the Dorrit clan to Arthur Clennam's father Gilbert through the mysterious codicil that memorialises the gentle musician's tutoring Arthur's birth-mother in her singing. Dickens also uses Frederick to reveal his brother William's short-comings, particularly his aristocratic haughtiness and utterly impractical nature. At the opening of chapter 19 of Book One, "Poverty," the novelist contrasts the aristocratic and condescending William with his unprepossessing sibling: "His brother Frederick of the dim eye, palsied hand, bent form, and groping mind, submissively shuffled at his side, accepting his patronage as he accepted every incident of the labyrinthian world in which he had got lost" (123). A musician earning a modest living, Frederick is constantly criticised by his brother for failing to uphold the family honour. In his study of Frederick, Eytinge shows him practising his art rather than walking by his brother's side in the "College-yard" of the Marshalsea prison. The American illustrator conveys his subject's gentle and melancholic nature, the description accompanied by this illustration of Frederick playing musical accompaniment for a stage play, as suggested by the stage and footlights above him and his music stand. The reader's understanding of the wizened musician in Chapter 20, "Moving in Society," is likely to have been conditioned by this earlier, ironic passage narrated by the patronising William himself:

His brother Frederick was much broken, no doubt, and it might be more comfortable to himself (the Father of the Marshalsea) to know that he was safe within the walls. Still, it must be remembered that to support an existence there during many years, required a certain combination of qualities &mdaash; he did not say high qualities, but qualities — moral qualities. Now, had his brother Frederick that peculiar union of qualities? Gentlemen, he was a most excellent man, a most gentle, tender, and estimable man, with the simplicity of a child; but would he, though unsuited for most other places, do for that place? No; he said confidently, no! And, he said, Heaven forbid that Frederick should be there in any other character than in his present voluntary character! Gentlemen, whoever came to that College, to remain there a length of time, must have strength of character to go through a good deal and to come out of a good deal. Was his beloved brother Frederick that man? No. They saw him, even as it was, crushed. Misfortune crushed him. He had not power of recoil enough, not elasticity enough, to be a long time in such a place, and yet preserve his self-respect and feel conscious that he was a gentleman. Frederick had not (if he might use the expression) Power enough to see in any delicate little attentions and — and — Testimonials that he might under such circumstances receive, the goodness of human nature, the fine spirit animating the Collegians as a community, and at the same time no degradation to himself, and no depreciation of his claims as a gentleman. Gentlemen, God bless you! [Book One, Chapter 19, "The Father of the Marshalsea in two or three Relations," page 130]

Played convincingly by veteran Irish actor and former Royal Shakespeare Company member Cyril Cusack (1910-1993) in the 1987 adaptation, directed and written by Christine Edzard and starring then fifty-year-old Derek Jacobi as Arthur Clennam, "the most ambitious cinematic adaptation of any Dickens novel" (Davis 217) had to run some 360 minutes to manage the complex plot and include the host of Dickensian originals, some twenty-three in all, headed by the "Father of British Cinema and Theatre," Alec Guinness (1914-2000), seventy-four at the time the film was made. In the more recent BBC One television adaptation (2008), Frederick Dorrit as played by James Fleet of Three Weddings and a Funeral (1994) fame has rougher edges, but his subtle characterisation benefits from Fleet's familiarity with similar characters from the Dickens canon:

He is one of a panoply of weak men in Dickens that people find charming — think of Newman Noggs in Nicholas Nickleby. Their hearts have often been broken in the past, and that has turned them into these men who can't fight their own corner. [BBC One interview with James Fleet]

After the scene in the Marshalsea, Dickens shows Frederick in his native element, the orchestra pit of the little theatre:

The old man looked as if the remote high gallery windows, with their little strip of sky, might have been the point of his better fortunes, from which he had descended, until he had gradually sunk down below there to the bottom. He had been in that place six nights a week for many years, but had never been observed to raise his eyes above his music-book, and was confidently believed to have never seen a play. There were legends in the place that he did not so much as know the popular heroes and heroines by sight, and that the low comedian had 'mugged' at him in his richest manner fifty nights for a wager, and he had shown no trace of consciousness. The carpenters had a joke to the effect that he was dead without being aware of it; and the frequenters of the pit supposed him to pass his whole life, night and day, and Sunday and all, in the orchestra. They had tried him a few times with pinches of snuff offered over the rails, and he had always responded to this attention with a momentary waking up of manner that had the pale phantom of a gentleman in it: beyond this he never, on any occasion, had any other part in what was going on than the part written out for the clarionet; in private life, where there was no part for the clarionet, he had no part at all. Some said he was poor, some said he was a wealthy miser; but he said nothing, never lifted up his bowed head, never varied his shuffling gait by getting his springless foot from the ground. Though expecting now to be summoned by his niece, he did not hear her until she had spoken to him three or four times; nor was he at all surprised by the presence of two nieces instead of one, but merely said in his tremulous voice, "I am coming, I am coming!" and crept forth by some underground way which emitted a cellarous smell. [Book One, Chapter 20, "Moving in Society," p. 136-137]

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit, il. Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1871.

Davis, Paul. "Little Dorrit." Charles Dickens A to Z; The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998. Pp. 209-217.

Fleet, James. "Interview." Little Dorrit, a major BBC One Dickens adaptation. London: BBC One. Accessed 25 April 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2008/10_october/13/dorrit7.shtml

Last modified 25 April 2011