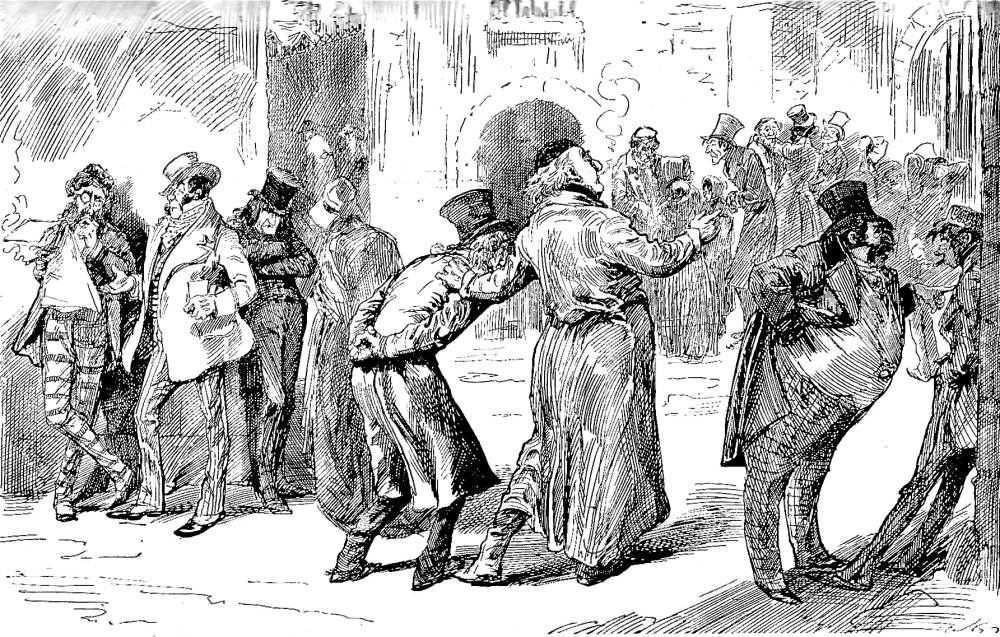

Through these spectators, the little procession, headed by the two brothers, moved slowly to the gate; — Page 217, in Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 36, "The Marshalsea Becomes an Orphan," which is also the title of Phiz's original steel engraving of the same momentous scene in which the brothers triumphantly exit The Marshalsea. This is Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's thirty-second illustration (and the final plate in the first book) for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, in the Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.4 cm high x 13.6 cm wide. The Chapman and Hall Household Edition woodcut is identical to that in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition, but the American caption is somewhat longer: Through these spectators, the little procession, headed by the two brothers, moved slowly to the gate. Mr. Dorrit, yielding to the vast speculation how the poor creatures were to get on without him, was great, and sad, but not absorbed — Book 1, chap. xxxvi..

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

In the yard, were the Collegians and turnkeys. In the yard, were Mr. Pancks and Mr. Rugg, come to see the last touch given to their work. In the yard, was Young John making a new epitaph for himself, on the occasion of his dying of a broken heart. In the yard, was the Patriarchal Casby, looking so tremendously benevolent that many enthusiastic Collegians grasped him fervently by the hand, and the wives and female relatives of many more Collegians kissed his hand, nothing doubting that he had done it all. In the yard, was the man with the shadowy grievance respecting the Fund which the Marshal embezzled, who had got up at five in the morning to complete the copying of a perfectly unintelligible history of that transaction, which he had committed to Mr. Dorrit's care, as a document of the last importance, calculated to stun the Government and effect the Marshal's downfall. In the yard, was the insolvent whose utmost energies were always set on getting into debt, who broke into prison with as much pains as other men have broken out of it, and who was always being cleared and complimented; while the insolvent at his elbow--a mere little, snivelling, striving tradesman, half dead of anxious efforts to keep out of debt--found it a hard matter, indeed, to get a Commissioner to release him with much reproof and reproach. In the yard, was the man of many children and many burdens, whose failure astonished everybody; in the yard, was the man of no children and large resources, whose failure astonished nobody. There, were the people who were always going out to-morrow, and always putting it off; there, were the people who had come in yesterday, and who were much more jealous and resentful of this freak of fortune than the seasoned birds. There, were some who, in pure meanness of spirit, cringed and bowed before the enriched Collegian and his family; there, were others who did so really because their eyes, accustomed to the gloom of their imprisonment and poverty, could not support the light of such bright sunshine. There, were many whose shillings had gone into his pocket to buy him meat and drink; but none who were now obtrusively Hail fellow well met! with him, on the strength of that assistance. It was rather to be remarked of the caged birds, that they were a little shy of the bird about to be so grandly free, and that they had a tendency to withdraw themselves towards the bars, and seem a little fluttered as he passed.

Through these spectators the little procession, headed by the two brothers, moved slowly to the gate. Mr. Dorrit, yielding to the vast speculation how the poor creatures were to get on without him, was great, and sad, but not absorbed. He patted children on the head like Sir Roger de Coverley going to church, he spoke to people in the background by their Christian names, he condescended to all present, and seemed for their consolation to walk encircled by the legend in golden characters, "Be comforted, my people! Bear it!"

At last three honest cheers announced that he had passed the gate, and that the Marshalsea was an orphan. Before they had ceased to ring in the echoes of the prison walls, the family had got into their carriage, and the attendant had the steps in his hand. — Book The First, "Poverty," conclusion of Chapter 36, "The Marshalsea becomes an Orphan," p. 219-220.

Commentary

Having received news of their good fortune, as in Darley's 1863 engraving Joyful Tidings, the Dorrits make a grand exit from the Marshalsea yard attended by a host of "collegians," incarcerated debtors. William Dorrit has decided to undertake an Italian tour, the nineteenth-century, bourgeois equivalent of the eighteenth-century, aristocratic Grand Tour. Phiz also shows the brothers making an earlier circuit of the exercise yard (for Frederick is not a prisoner of the Marshalsea, and is unfamiliar with its precincts) in The Brothers, so that, in essence, Mahoney had two models from which to work.

Whereas Phiz had treated the moment as a crowd scene, with all the Dorrits except Amy surrounded by the Collegians, Mahoney focuses on the distinguished, tailored figure of William Dorrit in stylish topcoat and beaver, deigning to pat upon the head ("like Sir Roger de Coverly going to church" in the celebrated Addison and Steele Spectator No. 2 essay) a pinafored child presented to him by her mother for a blessing, as if Mr. Dorrit were a visiting dignatary — or Christ in the leper colony. With his brother Frederick on his arm, apparently reluctant to be an active participant in the farewell procession, the Father of the Marshalsea at the hour of noon appointed for the family's departure by carriage leads the party composed of a monocled Edward ('Tip') and the vain Fanny. Again, as in Phiz's panoramic treatment, Amy is nowhere to be seen, for she has fainted in her room from all the excitement. In the Mahoney illustration one receives no impression of the scene's context (the prison yard), and Plornish and Maggy are absent. Although the dilapidated prison was closed in 1842 and subsequently demolished, Phiz and Dickens would have had little trouble reconstructing from memory the walled yard overlooked by barred windows, James Mahoney, although born in 1810, had moved to London only in 1859, and therefore had little sense of what the prison yard must have looked like in the period when John Dickens was incarcerated there. Thus, Mahoney concentrates on William Dorrit's apotheosis rather than on the crowd and the architectural setting.

The Dorrits in the original, American Household, and Diamond Editions, 1857-1867

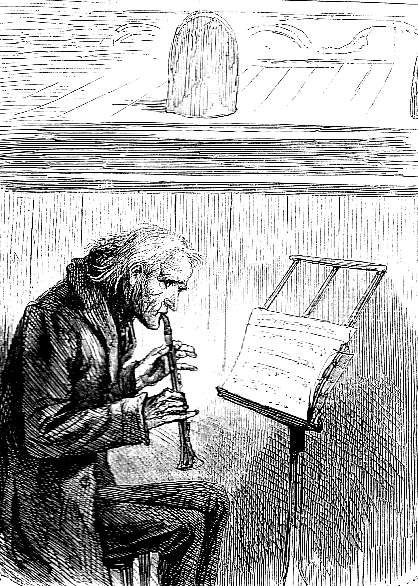

Left: F. O. C. Darley's 1863 frontispiece of the scene in which William Dorrit learns of his providential inheritance, Joyful Tidings (Volume 2). Centre: Hablot Knight Browne's first view of the prison's exercise yard, The Brothers (May 1856: Part 6). Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's interpretation of the musical younger brother, Amy's uncle, Frederick Dorrit (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's original serial illustration The Marshalsea becomes an orphan for Book 1, Ch. 36 (Part 10, September 1856), in which the Father of the Marshalsea triumphantly conducts his family through the central courtyard and off to freedom (stage right). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Furniss's revision of Phiz's steel engraving and of Mahoney's composite woodblock of William and Frederick in the "Old College" yard, The Dorrit Brothers in the Marshalsea, Book One, Ch. 19 (1910). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 19 March 2016