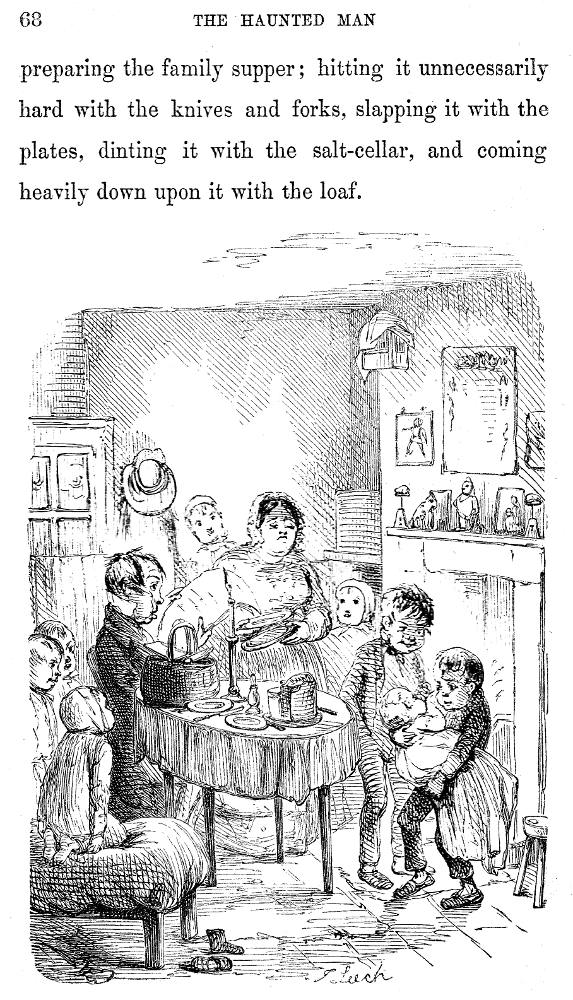

The Tetterby's Temper by Harry Furniss. 1910. 9 cm high x 14 cm wide, vignetted. The Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition, VIII, facing 353. Original caption: Mrs. Tetterby laid the cloth, but rather as if she were punishing the table than preparing the family supper; hitting it unnecessarily hard with the knives and forks, slapping it with the plates, dinting it with the salt-cellar, and coming heavily down upon it with the loaf. — Haunted Man, 355. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

"Ah, dear me, dear me, dear me!" said Mrs. Tetterby. "That's the way the world goes!"

"Which is the way the world goes, my dear?" asked Mr. Tetterby, looking round.

"Oh, nothing," said Mrs. Tetterby.

Mr. Tetterby elevated his eyebrows, folded his newspaper afresh, and carried his eyes up it, and down it, and across it, but was wandering in his attention, and not reading it.

Commentary

Furniss had a rich tradition on which to draw for his realisations of the scenes of domestic comedy involving the lower-middle class Tetterbys, whom Dickens seems to have intended to mine the sentimental strain represented by the Cratchits in the initial Christmas Book. That the comedy is a bit forced becomes evident when one studies the original illustrations of John Leech. In fact, Dickens had specifically designed the Tetterby family scenes with Punch illustrator Leech in mind. In consequence, given the very different proclivities of the other illustrators that Dickens had recruited for The Haunted Man in the autumn of 1848, the first edition of the novella still seems "a baffling mixture of intensity and eccentricity" (Cohen 148), with the domestic comedy of the news agent's family and the Swidgers sharply contrasting the eerie melodrama of the haunted chemistry professor in the accompanying illustrations. Leech's illustrations to a certain extent control the tone of the narrative-pictorial program because he contributed more composite woodblock engravings than any other artist commission for the project.

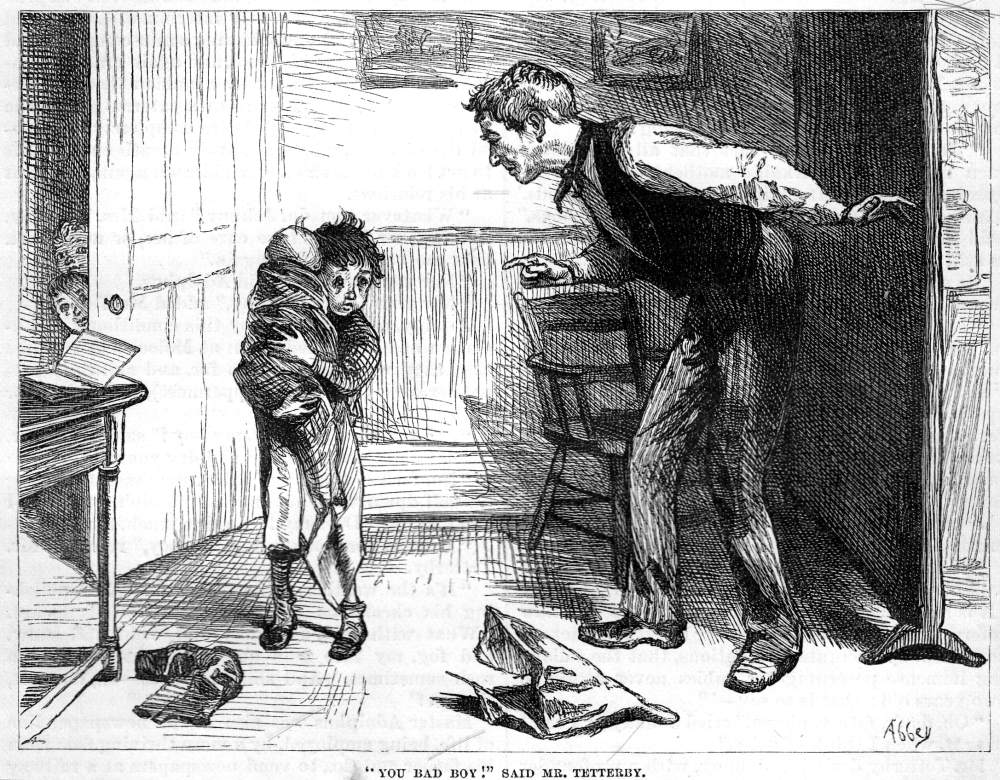

Providing five of the book's original seventeen illustrations for the 1848 volume, caricaturist Leech deals with all three sets of characters, but seems most comfortable with mining the vein of domestic comedy. Thus, although Leech could easily be surpassed by later illustrators in his handling of Redlaw and the boy, his Tetterby illustrations were a challenge for the Diamond Edition illustrator (Sol Eytinge, Jr.), the Household Edition illustrators E. A. Abbey and Fred Barnard, as well as for Harry Furniss over thirty years later, when artistic styles for book illustration had become more impressionistic. Although Furniss probably had not have seen the 1867 Diamond Edition illustration entitled The Tetterbys, Eytinge's version, like Furniss's, is especially successful at capturing the single-minded concentration of the usually genial Adolphus Tetterby as he attempts read, oblivious to the antics his various offspring in the overcrowded parlour. Abbey's Tetterby, in contrast, is anything but benevolent in his confrontation with Johnny. Furniss provides a dynamic tension between the mildly interrogative husband, constantly interrupted in his newspaper reading, and his very substantial wife, who dominates the composition by standing at the table, giving her physically slight husband a sour look.

Furniss in making the scene acceptable to early twentieth-century tastes has radically adjusted the composition; comparing his composition to Leech's, we can see that he has moved Tetterby from left to right and Mrs. Tetterby from centre to far left; and modelled the three chief figures far more effectively: the substantial Mrs. Tetterby (left), Johnny carrying the weighty Sally (centre, instead of far right in Leech's composition), and Adolphus Tetterby, Sr. (far right), swinging around in his chair as he attempts to read the large newspaper sheet, folded in half. Gone entirely is the familial hearth and mantelpiece, from the vantage point of which we witness the scene; accordingly, Furniss offers readers none of the homey bric-a-brac from Leech's version. More significantly, whereas Leech's 1848 figures remain amusing caricatures verging on the principals of a cartoon, these 1910 Tetterbys — two adults and nine children — coexist in a larger space, despite the small dining table. Furniss has also taken pains to incorporate Mr. Tetterby's newspaper screen (upper right). He manages all his characters and properties with compositional aplomb, but unfortunately fails to communicate as Leech does the essential humour in the scene. However, Furniss's version is not nearly so chaotic as that of the 1848 original, and is much closer in spirit to Abbey's realistic treatment in the 1876 American Household Edition. Like Abbey, Furniss gives us a respectably clad, thoroughly middle-class Tetterby, rather than Leech's frowsy, harassed, ill-kempt news agent trying to read a news sheet in the midst of domestic turmoil. Furniss's altering the configuration of the illustration from the vertical to the horizontal lends a much freer sense of space to the full-page composition, permitting him to accommodate all elements of the Tetterbys' parlour without the overwhelming sense in Leech's small-scale illustration of the figures being hemmed in by properties. Furniss comfortably incorporates such textual elements as Mrs. Tetterby's bonnet, the newsagent's screen, the open cupboard, and the anxious children watching their parents from the rear of the extended space.

Related Materials and Details

- The Christmas Books of Charles Dickens

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s second illustration for The Haunted Man (1867)

- Felix O. C. Darley's frontispiece for the second volume of Christmas Stories, a character study of the brooding protagonist and his double, As he leaned his arm upon the elbow of his chair, ruminating before the fire (1861)

- A. E. Abbey's Household Edition illustrations for The Christmas Books (1876)

- Fred Barnard's Household Edition illustrations for The Christmas Books (1878)

Pertinent Illustrations in Earlier Editions: 1848, 1867, 1876, and 1878

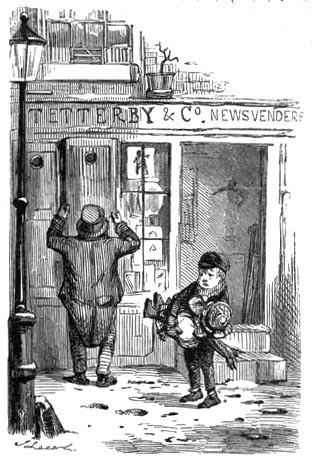

Left: Leech's The Tetterbys (1848); centre, Leech's Johnny and Moloch (1848); right: Barnard's British Household Edition cut with the lengthy caption: It roved from door-step to door-step, in the arms of little Johnny Tetterby, and lagged heavily at the rear of troops of juveniles who followed the Tumblers (1878).

Eytinge's Diamond Edition cut The Tetterbys (1867).

Abbey's American Household Edition cut "You bad boy!" said Mr. Tetterby (1876).

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "John Leech." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. , 1980, 141-51.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910, VIII, 79-157.

__________. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

__________. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

__________. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Illustrated by John Leech, John Tenniel, Frank Stone, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture Book. Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 4, "The Chord of the Christmas Season." Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982, 62-93.

Created 30 July 2013

Last modified 5 January 2020