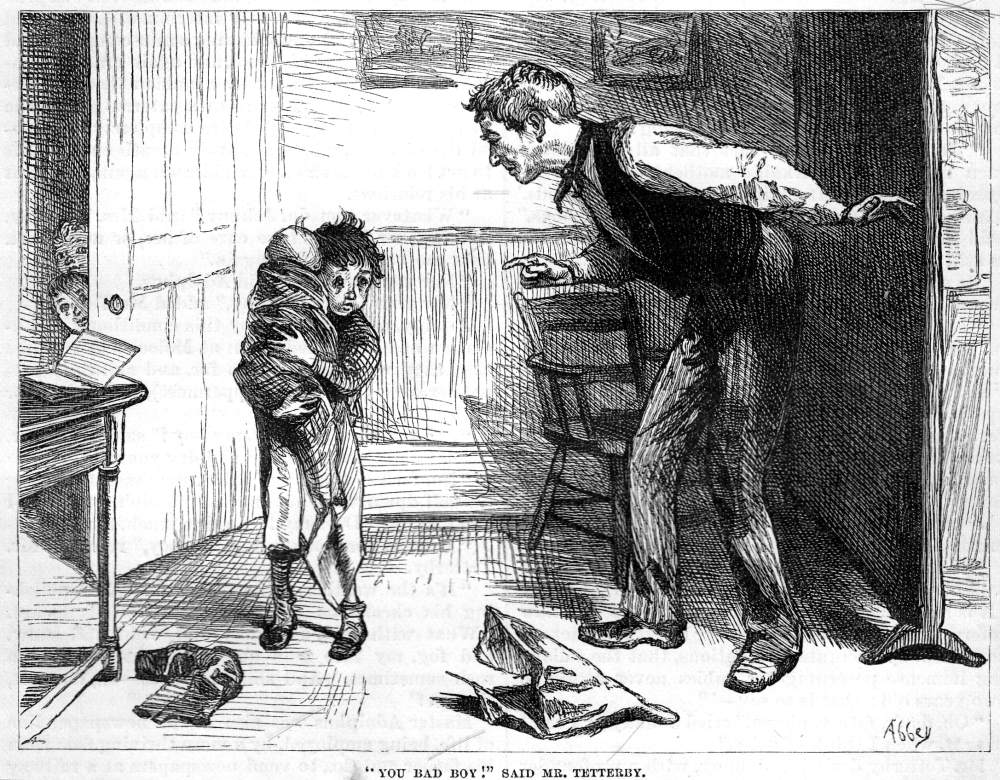

"'You bad boy!' said Mr. Tetterby" by E. A. Abbey. 10.2 x 13.4 cm framed. From the Household Edition (1876) of Dickens's Christmas Stories, p. 153. Dickens's The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain was first published for Christmas 1848. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The Passage Illustrated about Johnny and "Moloch" Tetterby

Tetterby himself, however, in his little parlor, as already mentioned, having the presence of a young family impressed upon his mind in a manner too clamorous to be disregarded, or to comport with the quiet perusal of a newspaper, laid down his paper, wheeled, in his distraction, a few times round the parlour, like an undecided carrier-pigeon, made an ineffectual rush at one or two flying little figures in bed-gowns that skimmed past him, and then, bearing suddenly down upon the only unoffending member of the family, boxed the ears of little Moloch's nurse.

"You bad boy!" said Mr. Tetterby, "haven't you any feeling for your poor father after the fatigues and anxieties of a hard winter's day, since five o'clock in the morning, but must you wither his rest, and corrode his latest intelligence, with your wicious tricks? Isn't it enough, sir, that your brother 'Dolphus is toiling and moiling in the fog and cold, and you rolling in the lap of luxury with a — with a baby, and everything you can wish for," said Mr. Tetterby, heaping this up as a great climax of blessings, "but must you make a wilderness of home, and maniacs of your parents? Must you, Johnny? Hey?" At each interrogation, Mr. Tetterby made a feint of boxing his ears again, but thought better of it, and held his hand.

"Oh, father!" whimpered Johnny, "when I wasn't doing anything, I'm sure, but taking such care of Sally, and getting her to sleep. Oh, father!" ["Chapter Two: The Gift Diffused," American Household Edition, p. 153; British Household Edition, p. 170]

E. A. Abbey's illustration of Johnny and "Moloch" compared to those by John Leech and Fred Barnard

As Dickens's original illustrators — John Leech, Clarkson Stanfield, joined by John Tenniel, and Frank Stone, who replaced Richard Doyle and Daniel Maclise — realised, Dickens's last Christmas Book offered plenty of material for realising moments of character comedy, pathos, the supernatural, and the picturesque. Once again, however, the British and American Household Editions of The Christmas Books offer illustrations largely lacking in these respects, the realism of Barnard and Abbey being entirely the wrong mode for the weird cautionary tale. As a cartoon in the Leech manner, the congested parlour and clamouring Tetterby children look humorous enough, but the careful realism of the Sixties style fails to convey anything of Dickens's verbal comedy. In Barnard's illustration, we have a street full of children — a minor moment in the narrative. In the parallel American Household Edition scene, we cannot even discern Mr. Tetterby's facial expression fully as he admonishes second-eldest son, Johnny, for interrupting him as he attempts to escape into the great (adult) world reported in the daily paper. Johnny, the victim, utterly innocent of creating any such disturbance, does not attempt to defend himself against his father's accusations and mistreatment, even as the actual offenders (the younger Tetterby children) anxiously regard the scene through the partially open door. Exasperated, the news agent has thrown his paper on the floor, centre. Immediately behind him is the screen that divides the little parlour from the shop proper in the Jerusalem Buildings, near the Old College.

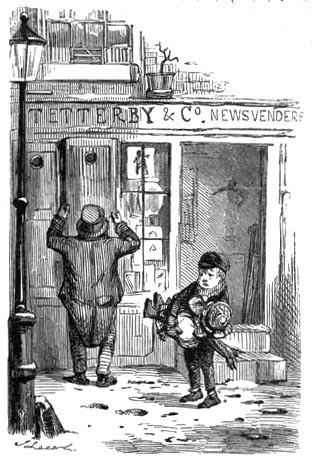

Fred Barnard's riotous street scene with Johnny (centre) carrying Moloch at least conveys a sense of the "surplus population" of working-class children in the London of the 1840s, so numerous a throng that they must bring themselves up, even as Johnny is given sole responsibility for his sister Sally. Neither Barnard's nor Abbey's illustration has the charm of Leech's "The Tetterbys," however, which also has the virtue of showing the entire family and their cramped quarters rather than merely the children, as in Barnard's illustration, or Johnny, Moloch, and their father in Abbey's.

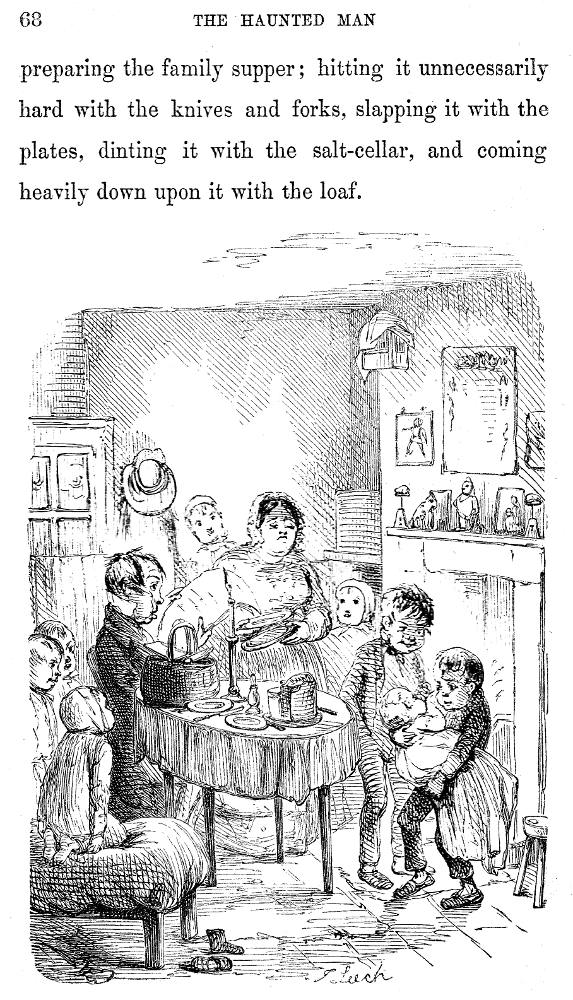

The original cartoon on p. 68 entitled "The Tetterbys" accomplishes a number of narrative-pictorial tasks that neither Barnard nor Abbey attempted to address. With his illustration sharing the page with the text realised, Leech has seamlessly integrated his illustration of Mrs. Tetterby's attempting to set the table for dinner while her husband and sons look on, the image below coinciding exactly with the line "slapping [the table] with the plates" (p. 68). Leech's interpretation of the lower-middle class family is that family life is relentlessly communal, and young children are omnipresent: there is non escape for either parent. Abbey, adding a combative element to lower-middle-class family life, more realistically dramatizes this point by showing Mr. Tetterby turn on the hapless Johnny, the only child who is in fact not a disturber of his peace. Abbey, however, replaces the boxing of the ears (domestic abuser being hardly the impression he wished to convey of the put-upon father) with the accusatory finger. As Mr. Tetterby (a far more slender fellow than Leech's original comic parent) swings around on Johnny, the actual culprits watch through the partially open door (left). At least Abbey's illustration, lacking in Leech's comedy, energy, and detail though it may be, advances the reader's understanding of the secondary characters, whereas Barnard's merely establishes the fact that the area around the Jerusalem Buildings is overrun with children.

Leech's exuberant cartoon versus Barnard's modelled group portrait and Abbey's more prosaic treatment: left: Leech's "The Tetterbys"; centre, Leech's "Johnny and Moloch"; and, right, Barnard's "It roved from door-step to door-step, in the arms of little Johnny Tetterby, and lagged heavily at the rear of juveniles who followed the tumblers, etc.".

The original John Leech cartoon of 1848 depicts the boisterous chaos of the Tetterbys' domestic establishment, without conventional Victorian sentimentality, despite idealised pictures of the royal family's parade of infants and toddlers that occasionally appeared in the illustrated press of the period, notably The Illustrated London News. The Punch cartoonist captures the essence of Dickens's exuberant domestic comedy and the text's gross exaggeration of the imposition of the massive infant on the responsible Johnny, a scene surely drawn from Dickens's own childhood in the cramped quarters of the many homes rented by John Dickens for what must have seemed to young Charles, the second-oldest, as an ever-expanding brood. Leech, shortly to be joined on the staff of Punch by fellow Haunted Man illustrator John Tenniel after Richard Doyle's resignation in 1850 over the journal's anti-Catholic stance, naturally falls into the mode of caricature and lampoon here. Whereas the Punch-like illustration "The Tetterbys" indicates that the struggling newsagent and his incompetent wife have seven children, the author at the point of writing (October-30 November 1848) had a growing brood of six children — and Catherine was very pregnant that autumn with their seventh child, who would be Christened "Henry Fielding Dickens" (born January 1849); but it may well have seemed to Dickens, struggling to find time for sustained writing and having had to put off the latest Christmas Book by a year, that he and Catherine, married twelve years, already had a brood of Tetterby dimensions, there being four sons and two daughters ranging in age that fall from eleven to one. In contrast to the Dickenses, the Tetterbys have only one daughter (the infant Sally, dubbed in the Dickens family manner "Moloch," after the Philistine devourer of children, and therefore by extension, childhood),the perpetual burden of the second-oldest son, Johnny, seen struggling under his charge in the centre of Leech's wood engraving) but six sons. The cartoon-like style and cramped parlour are both well-suited to Leech's subject, the "downside" (as we might say today) of the strained domestic circumstances depicted far more optimistically in the Cratchit family of the first Christmas Book. "The very looseness of Leech's lines in his pictures of Johnny coping with baby Moloch at home (II, 422) and abroad (III, 361) reinforces the good humour" (Cohen 149). In contrast to Leech's rough exuberance, Barnard offers a crowded street scene of modelled figures in vigorous motion, as if the children constitute a mob.

American illustrator E. A. Abbey has combined a visual introduction of Mr. Tetterby in his shop with John Leech's "Johnny and Moloch" in his second illustration for the novella, "'You bad boy!' said Mr. Tetterby" (p. 153), but fails to capture either Johnny's frustration or the sheer size of "Moloch," who in the American Household edition illustration does not seem so very large for a bavy. Abbey's lacks the detailism of Leech's densely-packed parlour scene, with its diminutive dining table and bric-a-brac effectively communicating the text's sense of the inadvertent tyranny of the Tetterby children and their father's feeling of being oppressed, and unable to concentrate on reading his paper. Significantly, Dickens has identified the young father with the publishing trade, although the hapless news vendor merely has to market and not actually generate printed matter; perhaps Dickens saw Tetterby as an extension of himself, surrounded by numerous progeny and unable to find a moment's peace. An only child, Leech must have wondered how his friend Charles Dickens could have grown up in such a chaotic domestic situation. The novelist, the second of seven siblings, lost a brother and a sister in childhood, and might well as a child have been made the "baby-minder" for Letitia, four years his junior, and even Harriet, born in 1819. The domestic life of the urban family enduring trying economic circumstances may reflect that of John and Elizabeth Dickens in Camden Town, London, in the early 1820s, prior to John's incarceration in the Marshalsea Prison for debt in 1824.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting, color correction, and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Brereton, D. N. "Introduction." Charles Dickens's Christmas Books. London and Glasgow: Collins Clear-Type Press, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Il. John Leech, John Tenniel, Frank Stone and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

James, Henry. Picture and Text. New York: Harper and Bros, 1893. Pp. 44-60.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 2 January 2013