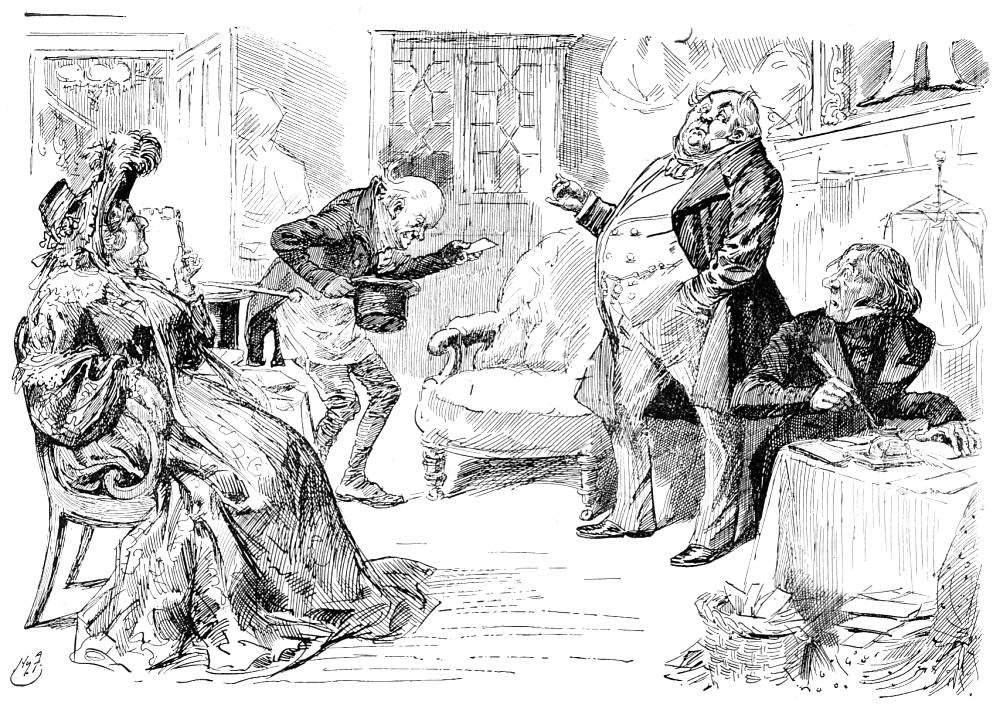

Trotty before Sir Joseph by Harry Furniss. 1910. 10 cm high x 14.4 cm wide. The Chimes in The Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing VIII, 97. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Toby wiped his feet (which were quite dry already) with great care, and took the way pointed out to him; observing as he went that it was an awfully grand house, but hushed and covered up, as if the family were in the country. Knocking at the room-door, he was told to enter from within; and doing so found himself in a spacious library, where, at a table strewn with files and papers, were a stately lady in a bonnet; and a not very stately gentleman in black who wrote from her dictation; while another, and an older, and a much statelier gentleman, whose hat and cane were on the table, walked up and down, with one hand in his breast, and looked complacently from time to time at his own picture — a full length; a very full length — hanging over the fireplace. ["Second Quarter," 103]

Commentary

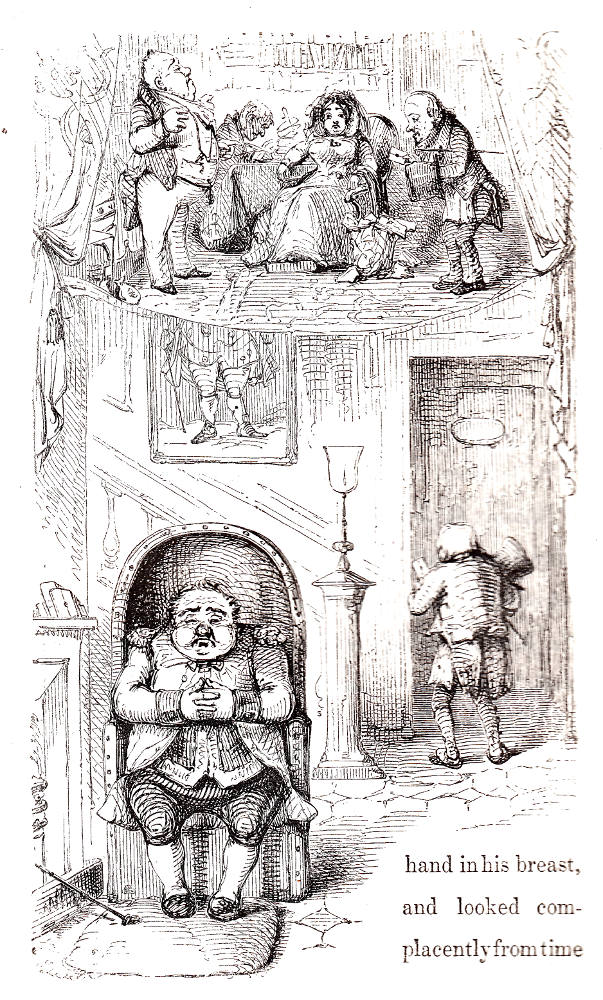

Furniss provides a relatively straightforward rendering of the self-important Member of Parliament, Sir Joseph Bowley, and does not attempt to match the temporal complexity of the original edition's wood engraving Sir Joseph Bowley's (see below, dropped into the letterpress. The "illogical movement of time associated with the fairy tale" (Solberg 103) is well exemplified by Leech's dual scene in which, bending the dimension of time, the 1844 illustrator has shown two related scenes to convey the protagonist's experiences at the Tory MP's townhouse. Furniss suggests the Bowleys' conspicuous consumption by their clothing and sheer bulk. Trotty, overawed by the great man, does not even look at him directly as he presents Alderman Cute's note. The lithograph corresponds to the situation in the extended caption (in fact, an abbreviated quotation) beneath the plate's title, although all we see of the MP's full-length portrait above the mantlepiece is his feet and trouser-cuffs: “Toby found himself in a spacious library, where, at a table strewn with files and papers, were a stately lady in a bonnet; and a not very stately gentleman in black. ‘What is this?” said the gentleman. ‘Mr. Fish, will you have the goodness to attend?’ ( 103).

In contrast to Leech's cartoon-like rendering of the scene, Furniss has dealt with it in a far less caricatural mode, emulating Fred Barnard's treatment in The Poor Man's Friend in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition. Furniss is a little less realistic than Barnard, although he disposes the figures in the scene in a somewhat theatrical manner and provides little depth of field. In these respects, Furniss's treatment assimilates the theatricality of Leech's plate and the somewhat exaggerated, bombastic characters of Sir Joseph and Lady Bowley while modelling the four figures in the realistic manner of Barnard.

However, Furniss departs from his visual precedents by reversing the positions of the four figures, so that, whereas tLeech and Barnard have the pompous Sir Joseph to the left, the secretary (Mr. Fish) rear of right-centre, and Lady Bowley and Trotty (a study in contrasting fashions) to the right, Furniss in the lithograph has a less-than-attractive and much overdressed Lady Bowley to the right, Trotty centre (the open door of the library indicating that he has just entered upper right), a stuffed chair echoing Sir Joseph's portly bulk as he dictates a letter (right of centre), and the secretary, Mr. Fish, who is identified by his quill pen and wastebasket full of papers (lower right). Whereas the 1844 illustration had only a few books to suggest the setting, Furniss includes a glass-doored book cabinet, a fireplace and screen, and even the feet of the portrait hanging over the fireplace, as in Dickens's text. While Lady Bowley seems "stately" and richly dressed in Furniss's illustration, she is hardly the young (albeit, aloof) beauty of Fred Barnard's version, in which Trotty looks directly at the aristocrats, rather than down, as in Leech's, in humility before such grand folk. Bowley's considerable paunch, covered by a double-breated white waistcoat, might remind the reader of the userer in Furniss's earlier Phantoms in the Street and the same corpulent banker in Leech's Christmas Carol illustration Ghosts of Departed Usurers. A telling detail in Furniss's revision is Lady Bowley's lorgnette, which implies her inability to see such insignificant street persons as the humble ticket-porter. One may also note how each artist has dressed Sir Joseph in the latest upper-class fashion so that his early Victorian tailcoat, stirrup pants, and waistcoat morph into their late Victorian equivalents in Barnard and a fin de siecle mode in Furniss. Trotty is consistently dressed according to his occupation, but is rather balder in Furniss's illustration — as is Sir Joseph.

Whereas in the previous year's Christmas Book, A Christmas Carol, Dickens had focussed on an individual miser's attitudes as hostile to the welfare of the working class, in The Chimes he details particular members of the political establishment (urban Tory, Alderman Cute, landed aristocrat Sir Joseph, and the statistician Filer, for example) as conspiring against such upstarts of labour as Will Fern. Although the original book's illustrations delineate effectively all these pasteboard villains, the later illustrators drop either Sir Joseph (as is the case with Abbey) or Alderman Cute (as is the case with Barnard. They also reduce the 1844 text's social criticism by omitting the down-and-out Richard, and even (with the exception of Barnard) the "fallen" Lilian and the incendiary Fern, a poor Dorset labourer who by becoming a rick-burner and political agitator exemplifies in his behaviour and denunciation of the authorities the discontent of the period's Chartists.

Related Materials and Details

- The Christmas Books of Charles Dickens

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s single illustration for The Chimes (1867)

- A. E. Abbey's Household Edition illustrations for The Christmas Books (1876)

- Fred Barnard's Household Edition illustrations for The Christmas Books (1878)

- Charles Green's illustrations for Dickens's The Chimes (1912)

Related Illustrations from Earlier Editions

Left: John Leech's Trotty before Sir Joseph (1844); Right: Fred Barnard's The Poor Man's Friend (1878).

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. , 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844 [dated 1845].

__________. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910, VIII, 79-157.

__________. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

__________. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-18.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 4, "The Chord of the Christmas Season." Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982, 62-93.

Welsh, Alexander. "Time and the City in The Chimes." Dickensian 73, 1 (January 1977): 8-17.

Created 20 June 2013

Last modified 1 January 2020