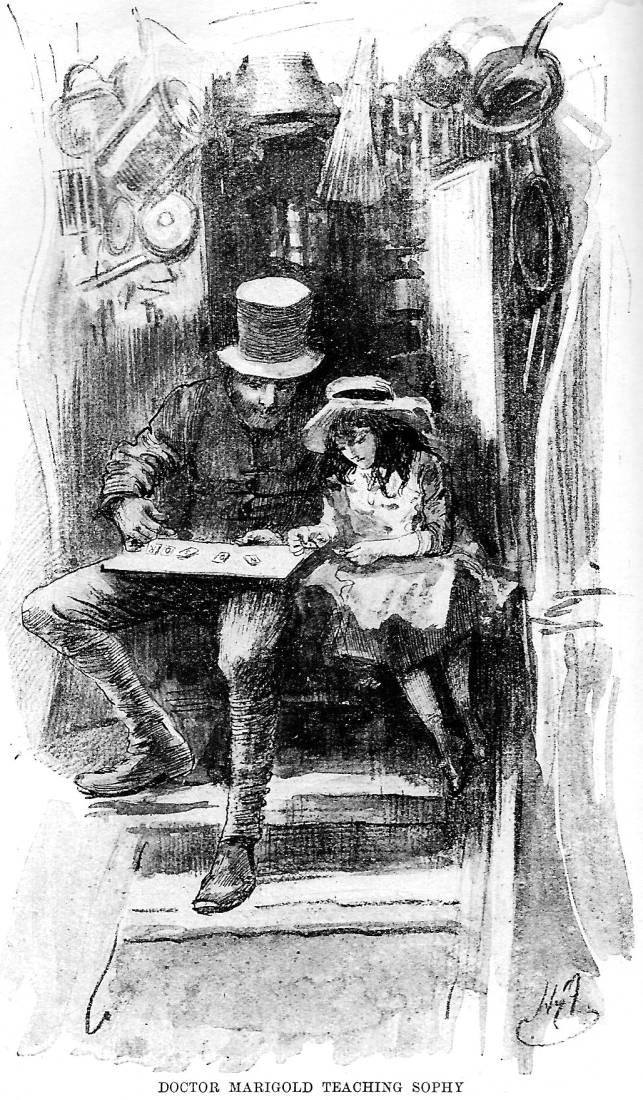

Doctor Marigold teaching Sophy

Harry Furniss

1910

14.5 x 8.5 cm vignetted

Dickens's Christmas Stories, Vol. XVI of The Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing page 481.

The 1865 Christmas framed tale Doctor Marigold's Prescriptions contained the introduction and conclusion by Dickens himself, as well as one of the inset stories, "To Be Taken with a Grain of Salt" (since reprinted in Two Ghost Stories as "The Trial for Murder" — and further extraneous material by his staff-writers at All the Year Round as the stories that her adoptive father writes for the deaf-and-dumb child. [Commentary continued below.]

[Click on image to enlarge it, and mouse over to find links.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

It was happy days for both of us when Sophy and me began to travel in the cart. I at once give her the name of Sophy, to put her ever towards me in the attitude of my own daughter. We soon made out to begin to understand one another, through the goodness of the Heavens, when she knowed that I meant true and kind by her. In a very little time she was wonderful fond of me. You have no idea what it is to have anybody wonderful fond of you, unless you have been got down and rolled upon by the lonely feelings that I have mentioned as having once got the better of me.

You'd have laughed — or the rewerse — it's according to your disposition — if you could have seen me trying to teach Sophy. At first I was helped--you'd never guess by what — milestones. I got some large alphabets in a box, all the letters separate on bits of bone, and saying we was going to WINDSOR, I give her those letters in that order, and then at every milestone I showed her those same letters in that same order again, and pointed towards the abode of royalty. Another time I give her CART, and then chalked the same upon the cart. Another time I give her DOCTOR MARIGOLD, and hung a corresponding inscription outside my waistcoat. People that met us might stare a bit and laugh, but what did I care, if she caught the idea? She caught it after long patience and trouble, and then we did begin to get on swimmingly, I believe you! At first she was a little given to consider me the cart, and the cart the abode of royalty, but that soon wore off. [Chapter 1, "To Be Taken Immediately," pp. 483-484]

Commentary

Thus, the multi-part story as it originally appeared on 12 December 1865 was a collaborative effort by his staffers. The staff-writers who produced five of Doctor Marigold's "prescriptions" or stories that he provides for the second Sophy are among the least known of the writers associated with Dickens's weekly journals. Irish writer Rosa Mulholland (1841-1921) contributed "Not To Be Taken at Bed-Time"; Dickens's son-in-law, painter and writer Charles Allston Collins, "To Be Taken at the Dinner-Table"; children's writer Hesba Stretton (the nom de plume of Sarah Smith, 1832-1911), "Not To Be Taken Lightly"; novelist and journalist Walter Thornbury (1828-1876), "To Be Taken in Water"; and Mrs. Gascoyne (probably the obscure novelist Caroline Leigh Smith, 1813-1883), "To Be Taken and Tried." Furniss seems to have felt that the Doctor Marigold framed story was among the more significant in the two decades of seasonal offerings, for whereas he did not even illustrate “The Perils of Certain English Prisoners” (1857, Household Words), he provided three illustrations for the Marigold framed-tales, yet only one, for example, for the "two-season" Lirriper stories.

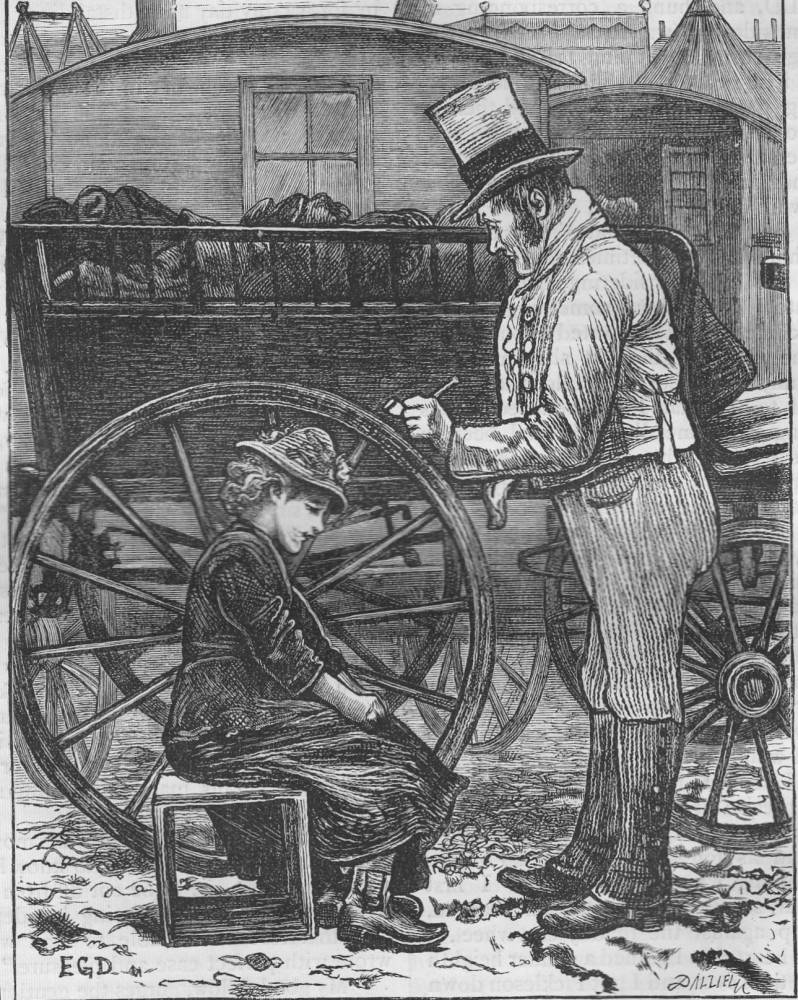

The Illustrated Library Edition "anthologized" version of the 1865 novella contained Edward Dalziel's Doctor Marigold. The 1876 American Household Edition of Christmas Stories contained E. A. Abbey's sixties style illustrations for The Christmas Books and plates for a few of the periodical stories, including the charming realisation of the visit by Sophy's daughter, "Grandfather!". Edward Dalziel was Chapman and Hall's choice of illustrator for its own Household Edition volume the following year; his execution of the illustration And at last, sitting dozing against a muddy cart-wheel, I come upon the poor girl who was deaf and dumb for this chapter, although hardly as dynamic as Furniss's pencil-and-ink sketch of Doctor Marigold teaching his adopted daughter how to read, does at least (if somewhat unemotionally and statically) explore the physical dimensions of cheap jack and the child, and effectively presents the wagon. Furniss seems to have felt that the two Doctor Marigold stories were among the more significant in the two decades of seasonal offerings, for whereas he did not even illustrate The Perils of Certain English Prisoners (1857, Household Words), he provided three illustrations for the two Marigold stories, yet only one, for example, for the Lirriper stories.

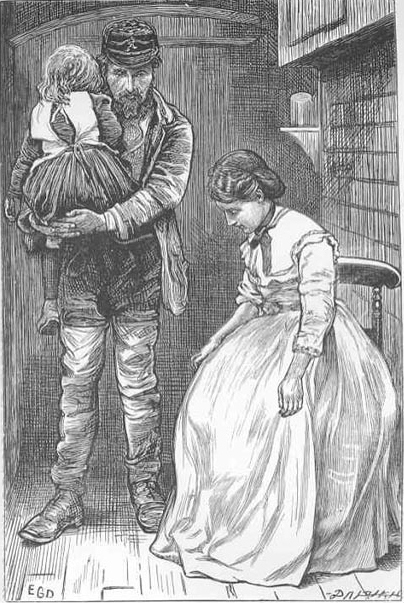

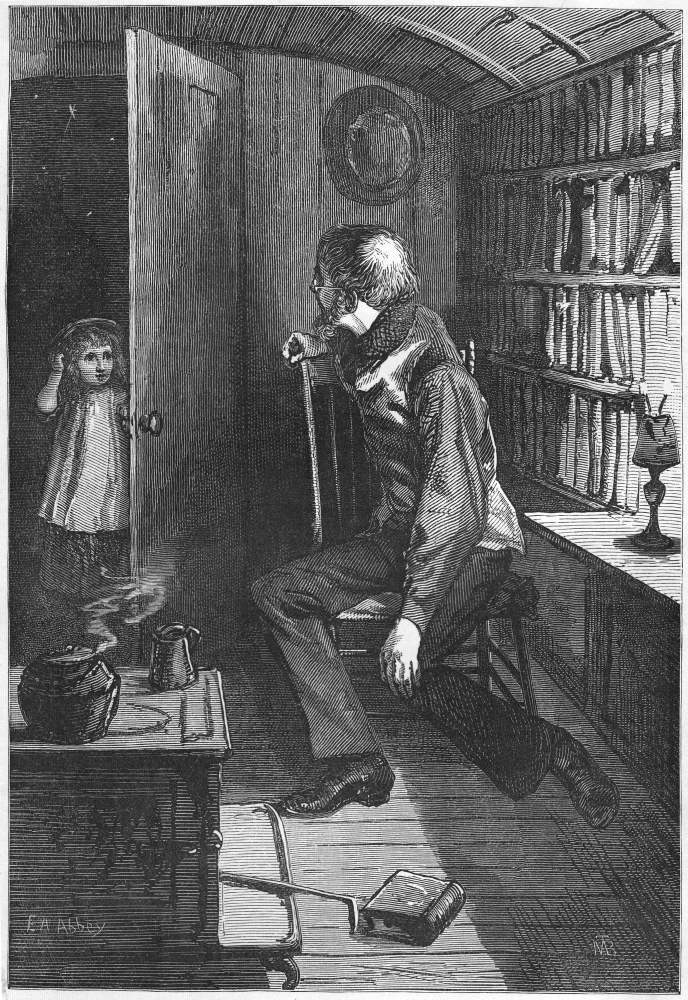

Dalziel's illustration entitled Doctor Marigold in the 1868 Illustrated Library Edition realizes the moment at which protagonist first meets the deaf-and-dumb child whom Providence provides in place of his own daughter, victim of prolonged abuse at the hands of his demented wife, whereas E. A. Abbey's realizes the touching passage in which Dickens describes through the persona of the aged cheap jack the return from China of the second Sophy, now a wife and mother, and her daughter.

Relevant Illustrated Library Edition (1868) and Household Edition (1876-77) Illustrations

Left: E. G. Dalziel's 1868 plate Doctor Marigold. Centre: E. A. Abbey's "Grandfather!" Right: Edward Dalziel's 1877 illustration "And at last, sitting dozing against a muddy cart-wheel, I come upon the poor girl who was deaf and dumb." [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

From its position in the text, the 1868 Dalziel illustration would appear to concern Doctor Marigold, the first Sophy (clinging to him for protection), and his young Suffolk wife; closer examination of the reflective and tranquil scene reveals the book-lined walls, which in turn suggest that this scene is comparable to Abbey's realisation of the return. (In fact, Furniss provides his own version of the reunion in Dr. Marigold's Little Visitor.) In contrast to the pensive stillness of this first Dalziel illustration and the delighted surprise of Marigold in his book-lined cart as his grand-daughter rushes in, Furniss realises a tranquil, undramatic scene in which, in a manner reminiscent of Arthur Hopkins in the monthly serialisation of Thomas Hardy's The Return of The Native (1878) in Belgravia, Furniss captures the satisfying reality of the masculine "portable house" that is the itinerant salesman's dwelling, place of business, and transportation combined, Diggory Venn's wagon in the scene The reddleman re-reads an old love letter (March 1878) from the Wessex novel being roughly equivalent. Furniss takes enjoyment in delineating such mundane objects as the cheap jack's pots and pans and other domestic utensils as he shows the father and daughter (in pinafore and staw hat) concentrating on sorting the blocks into meaningful configurations and bonding through learning.

Dickens and Education

Furniss's choice of subject here underscores Dickens's life-long interest in social issues, including the ragged schools, Urania Cottage, and the education of those with such disabilities as hearing impairment and blindness. As early as Oliver Twist (1837-39) Dickens was advocating for disadvantaged children. For example, in February 1846 Dickens wrote a letter to the Daily News about the good work he saw accomplished in London's ragged schools, a sentiment that he reiterated in "A Sleep to Startle Us" (13 March 1852) in Household Words, although by the time that Our Mutual Friend appeared in May 1864, Dickens was disappointed with the ragged schools, as his satire of such an institution in that novel, Book Two, Chapter One, indicates.

Here, Doctor Marigold teaches the deaf-and-dumb Sophy her letters through what educators currently term "manipulatives," blocks on which he has drawn letters so that the child can construct her own words, complementing the adoptive parent's direct instructional strategy of placing signs on everyday objects — including himself — so that through a species of whole language learning the child will connect objects with their names. The soft hues of pencil shading embue the illustration with the tenderness of the persona's memory of those days on the road when he felt that Providence had mercifully restored his dead daughter and brought him the companionship he sorely lacked after the child's death, his wife's suicide, and the demise of his faithful dog died at York in convulsions.

Diana Archibald has noted the importance of such causes as the education of the poor and disabled to Dickens as a young man, and in particular how his visit to the Perkins School for the Blind (incorporated in 1829) in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1842 influenced his attitude towards education for the blind as he was impressed with the work of the school's director, Samuel Gridley Howe, and Laura Bridgman, a deaf-and-blind girl who began attending the school in 1837. Indeed, although she was already thirteen when Dickens met her on his first American Reading Tour, Laura may have served as his model for Sophy Marigold; certainly she appears in her own right in the Boston chapters of American Notes for General Circulation in 1842. How much of this would have been apparent to Furniss is unclear, although he was intimately familiar with Dickens's life through John Forster's biography of his favourite author, and would have recognised through his extensive reading of the Dickens canon that deafness is rare in Victorian fiction, and that Sophy breaks type in going away to school and herself becoming a parent, despite societal apprehensiveness that such a dysfunction could be genetic. Doctor Marigold credits Sophy with her ability to learn written language as being a result of her natural quickness rather than taking any credit for his skill in signing objects and his loving persistence, the dominant quality of the Furniss illustration.

Bibliography

Archibald, Diana. "Laura Bridgman and Marigold's Sophie: The Influence of the Perkins Visit on Dickens." Dickens Society of America Symposium. Victoria College, University of Toronto. 5 July 2013.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. 2 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All The Year Round". Illustrated by Fred Walker, F. A. Fraser, Harry French, E. G. Dalziel, J. Mahony [sic], Townley Green, and Charles Green. Centenary Edition. 36 vols. London: Chapman & Hall; New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911. Vol. II.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Edward Dalziel, Harry French, F. A. Fraser, James Mahoney, Townley Green, and Charles Green. The Oxford Illustrated Dickens. Oxford, New York, and Toronto: Oxford U. P., 1956, rpt. 1989.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 19 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876. Vol. III.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round." Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877. Rpt., 1892. Vol. XXI.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 16.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. "Christmas Stories." The Oxford Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 100-101.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustration

Harry

Furniss

Next

Last modified 26 September 2013