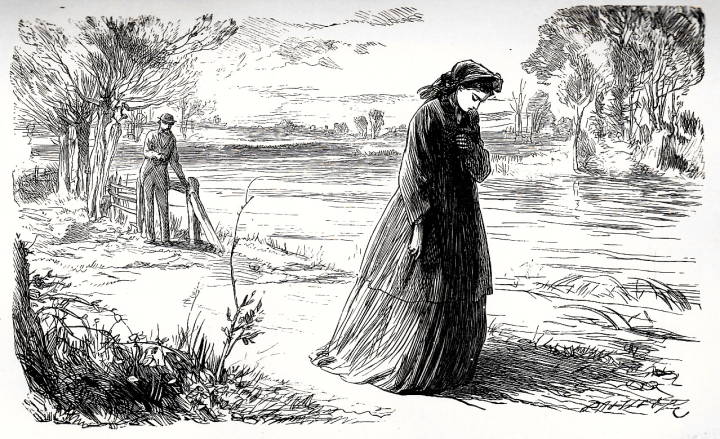

Lizzie Hexam to the Rescue by Harry Furniss. 9 cm by 13.6 cm, or 3 ½ by 5 ½ inches, framed. Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, facing XV, 737, in Book IV, “A Turning,” Chapter VI, “A Cry for Help,” in The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

A sure touch of her old practised hand, a sure step of her old practised foot, a sure light balance of her body, and she was in the boat. Another moment, and she had cast off, and the boat had shot out into the moonlight. — Our Mutual Friend, p. 729.

Passage Illustrated: Lizzie Displays a Cool Head and Command of Her Craft

It was thought, fervently thought, but not for a moment did the prayer check her. She was away before it welled up in her mind, away, swift and true, yet steady above all — for without steadiness it could never be done — to the landing-place under the willow-tree, where she also had seen the boat lying moored among the stakes.

A sure touch of her old practised hand, a sure step of her old practised foot, a sure light balance of her body, and she was in the boat. A quick glance of her practised eye showed her, even through the deep dark shadow, the sculls in a rack against the red-brick garden-wall. Another moment, and she had cast off (taking the line with her), and the boat had shot out into the moonlight, and she was rowing down the stream as never other woman rowed on English water. [Book IV, “A Turning,” Chapter VI, “A Cry for Help,” 729]

Commentary: Climactic Action on the River

In “A Cry for Help” the daughter of Thames waterman Gaffer Hexam turns her practised skill with oars and skiff to good account as she comes to the rescue of her admirer, Eugene Wrayburn, who has just been assaulted by the envious and mentally unstable Bradley Headstone. Furniss's vigorous, impressionistic style is well suited to this dynamic scene in which Lizzie snatches her lover (whom she just rejected at the river-bank) from drowning near Plashwater Weir, where shortly Bradley Headstone himself will drown, according to Victorian conventions of poetic justice. Although perhaps mere coincidence, it was a sign of the times that in the year that the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910), illustrated by Harry Furniss, was published, suffragette spokesperson Emily Davies wrote Thoughts on Some Questions Relating to Women and in the House of Commons a bill was introduced to give voting rights to single and widowed females of a household, an initiative that would have granted young women such as Lizzie the right to vote.

The other nineteenth-century illustrators focussed on the romantic aspect of Lizzie's farewell scene (as in Marcus Stone's The Parting by the River, — see below) or the impending violence of the scene in the Household Edition. Furniss, however, working at the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, dares to realise an atypical aspect of the story, as one of the romantic heroines, the emotionally-conflicted girl of the working class, uses her workaday skills learned from her father to rescue the privileged young attorney. F. O. C. Darley in the fourth American "Household" Edition volume of 1866 had focussed in the frontispiece on Riderhood's surveillance of Headstone as he attempts to destroy the evidence of his involvement in what he believes to be the murder of the young lawyer in On the Track, that is, on the crime-and-detection aspect of the novel. But Furniss has seized upon one of the most suspenseful sequences in the final movement of the story which reverses the reader's conventional expectations about the hero's rescuing the heroine, an expectation reinforced by the new medium of motion pictures in an era when women were demanding political and social emancipation — and recognition of their potentialities beyond the hearth and home. Although Dickens's novel appeared just a decade after Coventry Patmore's idealisation of the woman's domestic function, The Angel in the House (1854-55), Lizzie is in many ways a much more complex, multi-faceted figure than Dickens's previous heroines — indeed, she strikes us today as the most modern, as Furniss points out by his selection of this scene of the dynamic Lizzie fearlessly acting in the male domain.

Although series editor J. A. Hammerton describes Lizzie in patriarchal terms in "Characters in the Story" — "daughter of Jesse Hexam; marries Eugene Wrayburn" [viii] — she appears a total of four times in twenty-eight Furniss illustrations, and occupies a prominent position (upper right) in the ornamental title-page Characters in the Story. She is one of two focal characters in the frontispiece, "Keep her out, Lizzie," and makes two solo appearances, in Lizzie Hexam's Vigil and Lizzie Hexam to the Rescue, in a narrative-pictorial sequence that involves only a very few individual studies other than Lizzie: Silas Wegg on his way to the Bower, and Bella's Baby. Thus, in a novel in which male characters predominate, Furniss accords a special prominence to Lizzie, who in so many ways violates the norms of the Victorian heroine, but by her courage, strength of character, and intelligence is worthy of development and concludes the story by crossing the class barrier. Furniss uses her as a foil to the more conventional female protagonist, Bella Wilfer, who is shown as feted, beautifully dressed, and mingling with upper-middle class society. Since chance plays a significant role in Lizzie's rescuing Wrayburn in that it is mere coincidence that she remembers seeing a boat at a convenient distance from the scene of the assault, Furniss sees her as a force, an agent of Providence.

Related Materials: Background, Setting, Theme, Characterization, and Illustration

- Imagination and Fragmentation of Human Bodies/Bodies Politic in Our Mutual Friend

- Understanding Jenny Wren: The Parent of an Alcoholic Father

- The debate over character and education

- The Story of Dickens's Last Complete Novel — a review of Sean Grass's Charles Dickens's "Our Mutual Friend": A Publishing History (2014)

- The Evening the Veneerings gave a banquet

- Sol Eytinge's illustrations for the novel (with commentaries)

- Marcus Stone's original illustrations for the novel (with commentaries)

- Illustrations by James Mahoney (1875)

- Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1866)

- Illustration by Harold Copping (1923)

Comparable Chapter Illustrations in the Original and Household Edition, 1865 and 1875

Left: Stone's sentimental interpretation of the scene in which Lizzie dismisses Wrayburn by the river, The Parting by the River (Part 17, September 1865). Right: Mahoney's suspenseful interpretation of the scene in which Headstone attacks the unsuspecting Eugene Wrayburn by the river, He had sauntered far enough. Before turning to retrace his steps, he stopped upon the margin to look down at the reflected night (Book IV, Ch. 6).

Related Materials

- Illustrations by Marcus Stone (40 plates from the Chapman and Hall edition of May 1864 through November 1865)

- Frontispieces by Octavius Carr Darley (4 photogravures from the Hurd and Houghton Household Edition of 1866)

- Illustrations by Sol Eytinge, Jr. (16 plates from the Ticknor and Fields' Diamond Edition of 1867)

- James Mahoney (58 plates from the Chapman and Hall Household Edition of 1875)

- Harry Furniss (28 lithographs from the Charles Dickens Library Edition, Vol. XV, 1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke (two studies from his designs for the Player's Cigarette Cards, 1910)

Scanned images, captions, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Brigden, C. A. T. "No. 17. Silas Wegg." The Characters from Charles Dickens as depicted by Kyd. Rochester, Kent: John Hallewell, 1978.

The Characters of Charles Dickens Pourtrayed in a Series of Original Water Colour Sketches by “Kyd.” London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, 1898[?].

Cordery, Gareth, and Joseph S. Meisel, eds. The Humours of Parliament: Harry Furniss's View of Late-Victorian Culture. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2014. [Review by Françoise Baillet]

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. The Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. 21 vols. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865]. Vol. XIV.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. VIII.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. Volume IX.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. XV.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. XVII. 441-442.

Vann, J. Don. "Our Mutual Friend, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, May 1864—November 1865." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 74.

Created 3 January 2016

Last modified 7 August 2025