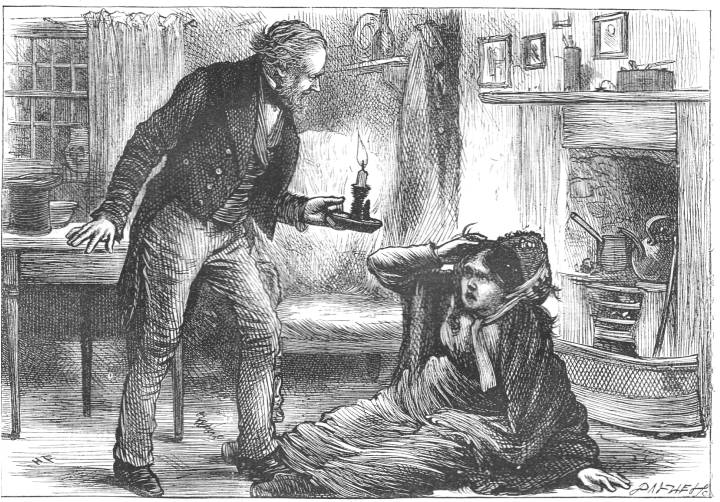

"'Heaven's Mercy, Woman!' He Cried, Falling Farther Off From The Figure. 'Has Thou Come Back Agen?'" by Harry French. Wood engraving. 1870s. 13.8 cm wide x 9.5 cm high. Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition. p. 32. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The high factory chimneys fed by the industrial furnaces of Dickens's Coketown cast no shadows throughout Harry French's programme of twenty illustrations for the British Household Edition of Hard Times. Even Stephen Blackpool's "disabled, drunken" wife seems to have been filtered by French's essentially middle-class pictorial imagination, so that her hair is scarcely "tangled" and her dress hardly the "tatters" that Dickens specifies in his description of a woman reduced to level of a "creature" through substance abuse and addiction. However, Stephen's beard, top hat, and tail-coat are plausible, given the historical context in which the artist drew them. Even the working class attempted to maintain a respectable appearance by shopping in second-hand clothing shops, acquiring what had been some seasons previous fashionable and what still had considerable wear left; we note that Stephen's coat (plates 6, 7, 8, and 11) seems somewhat out-of-date compared to the fuller frock-coats worn by Gradgrind (plates 1, 3, 4, and 16), Bounderby and Harthouse (plates 9 and 10), and Harthouse's stylish sports-jacket (plate 12).

Stephen's beard (purely the artist's invention) may reflect the style that came in after the Crimean War, when non-military gentlemen of fashion attempted to emulate the military beard: "As to whiskers, men were usually clean-shaven until the 1850s, when the soldiers returned from the Crimean War with beards. . . . . Soon, however, every respectable man sprouted one" (Pool 217). With respect to both beards and clothing, the lower classes usually attempted to follow the fashions set by the upper and then the upper-middle classes.

In The Industrial Refortmation of English Fiction: Social Discourse and Narrative Form 1832-1867 (1985), Catherine Gallagher makes the following observation about the origins of Stephen's wife:

In "'Divorce and Matrimonial Causes': An Aspect of Hard Times," Victorian Studies (Summer 1977): 401-12, John D. Baird argues persuasively for Dickens's use of actualcases in his portrait of Stephen Blackpool, whoser wife, Baird suggests, is not only alcoholic but adulterous and syphilitic as well. Nevertheless, under then-current divorce laws, Stephen's only remedy lies in the procedure Bounderby outlines -- three separate lawsuits and a private act of Parliament, at an estimated cost of two thousand pounds -- in order to be free to marry Rachael. So, with his fellow "average Englishmern," Stephen is, as Baird points out, "more likely to be struck by lightning than to be divorced." [288]

Last modified 21 April 2002