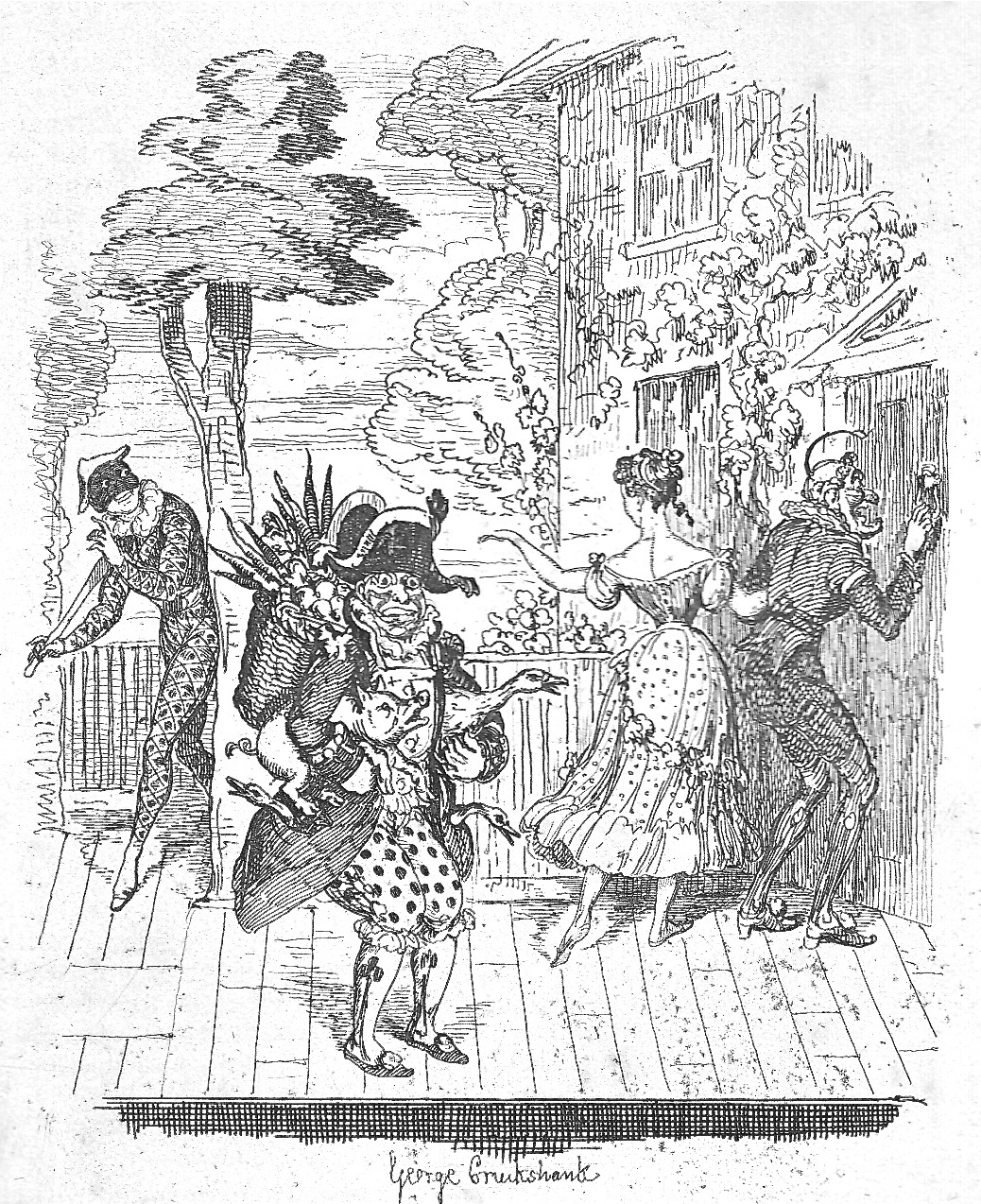

Live Properties

George Cruikshank, 1792-1878

1838

Etching on copper

10.4 x 8.3 cm

Facing page 156 in Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Edited by "Boz." With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> George Cruikshank —> Next]

Live Properties

George Cruikshank, 1792-1878

1838

Etching on copper

10.4 x 8.3 cm

Facing page 156 in Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Edited by "Boz." With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

On the 14th [in March 1808, Joey Grimaldi] received permission from Mr. Kemble [i. e., John Philip Kemble, manager of Covent Garden] to play for his sister-in-law's benefit at the Birmingham theatre, which was then under the management of Mr. Macready, the father of the great tragedian. Immediately upon his arrival, Grimaldi repaired to his hotel, and was welcomed by Mr. Macready with much cordiality and politeness, proposing that he should remain in Birmingham two, or, if possible, three nights after the benefit at which he was announced to perform, and offering terms of the most liberal description. Anticipating a proposal of this nature, Grimaldi had, before he left town inquired what the performances were likely to be at Covent Garden for some days to come. Finding that if the existing arrangements were adhered to, he could not be wanted for at least a week, he had resolved to accept any good offer that might be made to him at Birmingham, and therefore closed with Mr. Macready, without hesitation. After breakfast they walked together to the theatre to rehearse; and here Grimaldi discovered a great lack of those adjuncts of stage effect technically known as "properties:" there were no tricks, nor indeed was there anything requisite for pantomimic business. After vainly endeavouring to devise some means by which the requisite articles could be dispensed with, he mentioned his embarrassment to the manager.

"What! properties?" exclaimed that gentleman — "wonderful! you London stars require a hundred things, where we country people are content with one: however, whatever you want you shall have." — Here, Will, go down to the market and buy a small pig, a goose, and two ducks. Mr. Grimaldi wants some properties, and must have them."

The man grinned, took the money, and went away. After some reflection Grimaldi decided in his own mind that the manager's directions had been couched in some peculiar phrases common to the theatre, and at once went about arranging six pantomime scenes, with which the evening's entertainments were to conclude. While he was thus engaged, a violent uproar and loud shouts of laughter hailed the return of the messenger, who, having fulfilled his commission to the very letter, presented him with a small pig, a goose, and two ducks, all alive, and furthermore, with Mr. Macready's compliments, and he deeply regretted to say that those were all the properties in the house.

He accepted them with many thanks, and arranged a little business accordingly. He caused the old man in the pantomime and his daughter to enter, immediately after the rising of the curtain, as though they had just come back from market, while he himself, as clown and their servant, followed, carrying their purchases. He dressed himself in an old livery coat with immense pockets, and a huge cocked hat; both were, of course, over his clown's costume. At his back, he carried a basket laden with carrots and turnips; stuffed a duck into each pocket, leaving their heads hanging out; carried the pig under one arm, and the goose under the other. Thus fitted and attired, he presented himself to the audience, and was received with roars of laughter. — Chapter XIV, "1807 to 1808. Bradbury, the Clown — His voluntary confinement in a Madhouse, to screen an "Honourable" Thief — His release, strange conduct, subsequent career, and death — Dreadful Accident at Sadler's Wells — The Night-drives to Finchley — Trip to Birmingham — Mr. Macready, the Manager, and his curious Stage-properties — Sudden recall to Town," pp. 155-56.

Small Properties are generally hand-held items ranging from a sword to a briefcase which actors carry onto or around the stage. Also used loosely for "set dressing." Although now customarily abbreviated to "props," the term "property" was in use well into the nineteenth century. One may distinguish between "hand props" (used by actors to help tell the story during the performance, and easily picked up and put down by an actor), "personal props" (actually carried by an actor in his costume during a performance), and "properties" generally, everything on stage that is neither an element of scenery nor a part of a costume. In practical terms, a theatrical property is anything movable or portable on a stage or in a set, as distinct from actors, scenery, costumes, and lighting equipment, so that even food shown or consumed on stage (such as the goose in stage productions of A Christmas Carol) is technically "a property." Grimaldi extends the concept to include animals that are handled by actors. The Oxford English Dictionary identifies the first use of the abbreviation "props" in 1841. The term "property" in a theatrical context denotes any physical object owned by a theatre company that is neither an aspect of the set or the costuming.

It is and old maximum of the theatre that working with animals and children is dangerous because the cast can never be sure what such "properties" will do. Therefore, Grimaldi's undertaking a pantomime sketch featuring four farm animals was daring indeed, although the choice of the creatures who should be "live properties" was not his but Mr. Macready's. What we now regard the standard clown's costume and makeup are evident here beneath Grimaldi's servant's costume, so that the audience can see, as it were, two characters in one, or possibly three in one: the servant returned from marketing, the Clown, and the celebrated Joey Grimaldi himself — the most popular entertainer of the Regency period.

He was a great clown, a wonderful comedian and a superb dancer and acrobat. He made the Clown King — but he also preserved tradition. The costume he wore was the direct descendant of that worn by Arlecchino. For Grimaldi always had a white face — and the dirty marks were replaced by crescents and circles of blue and red. He had a kind of jerkin which was also white, but had patches of blue and red all over it. He had quite baggy "trunks" (they were almost breeches in his case) with a succession of little frills, one below the other, and had capacious pockets in which he stowed the goods he pilfered — you could see the string of sausages hanging out — which were the direct descendants of the baggy pants of Arlecchino.

He adapted the splay-footed walk when he needed it, and although he used no staff — he had his red hot poker instead, with which to "touch up" the policeman in later years, the watchman in HIS day — and anyone else who gave him trouble, to say nothing of poor old Pantaloon. So there was the tradition of the clown of Arlecchino still enshrined by Grimaldi, the supreme Clown. — W. Macqueen-Pope.

As Grimaldi added to the repertoire of the Clown, Harlequin became a more romantic and stylised figure. Grimaldi also created the traditional whiteface make-up design for the Clown. Originally the rustic or awkward booby designated as "Clown" on the English stage was a bumbling countryman or bumpkin whose buffoonery served as physical comic relief. As a lower-class rustic he usually wore tattered servants' garb. Parodying the dandy's clothing of the era, Grimaldi invented the more colourful, patterned costumes now associated with clowns, using breeches rather than trousers, the recent innovation of Beau Brummel. The distinctive red-and-white costume he wore on stage between 1801 and 1823 is now in the Museum of London. In Charles Dibdin's pantomime Peter Wilkins: or Harlequin in the Flying World (1800) at Sadler's Wells, Grimaldi reinvented the character of the Clown, transforming him into the central figure of the harlequinade. (The titles of the Christmas and Easter pantomimes of the nineteenth century continued the eighteenth-century theatrical convention of employing the word "Harlequin" first, even after the first decade of the 1800s, when Grimaldi's Clown came to dominate London pantomime, making his stage character, the colourful embodiment of chaos, as important as Harlequin himself.) Growing up in the poorer suburbs of Holborn and Clerkenwell, Joey was fascinated by the street life of the city so vividly recorded by Charles Dickens in Sketches by Boz (1836). His signature song, "Hot Codlings," which premiered in Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, The Golden Egg in 1806, dramatises the character of a street hawker selling baked apples. The song, which became his signature, was the last thing he did on the London stage. Grimaldi's subsequent popularity in London led to a demand for him to appear in provincial theatres throughout the British Isles, where he commanded large fees.

There are three other characters on stage worthy of comment: the old man (Pantalone) is a blocking figure, getting in the way of the romance between the young woman of the harlequinade, Columbine, and the tricky servant, Harlequin himself (left). These figures in the Birmingham production depicted by Cruikshank are consistent with the stock characters of the Commedia dell'Arte: a clown or Pierrot; the bumbling old father, Pantalone or Pantaloon; the naughty servant Arlecchino or Harlequin; a lover and his lady; and her servant girl (Columbine) who is in love with Arlecchino. What Grimaldi in the Cruikshank illustration is staging is apparently a variation on the setting up of the traditional "chase" scene in the Harlequinade in which the two lovers, Harlequin and Columbine, are being kept apart by Pantaloon, whose servants continually play tricks on him. In the chase the two lovers are pursued by her father and his servant, Clown. However, Grimaldi made a further innovation in the chase to emphasize the craziness of the harlequinade, the most exciting part of the "panto", because it is fast-paced and includes spectacular scenes, transformative magic, slapstick comedy, dancing, and acrobatics — he made Clown and Harlequin the principal antagonists. In his pursuit of the lovers, Columbine's foolish father is continually slowed down by his servant, Clown, and by a bumbling watchman or policeman. However, under Grimaldi, Clown became the principal schemer trying to thwart the lovers, and Pantaloon was relegated to being his assistant. In the Cruikshank illustration, the focal character for both the artist and the audience is the Clown, laden with produce and live poultry, and Columbine (waving to her lover, stage right), Harlequin, hiding behind a stage tree (left), and Pantaloon, entering his stage mansion (right) are merely supporting characters.

Left: George Cruikshank's depiction of a childhood scare, as Joey's father throws the lad (dressed as a monkey) towards the audience and the tether breaks, in Joe's debut into the Pit at Sadler's Wells in Chapter 1. Centre: Cruikshank's depiction of John Philip Kemble reprimanding Davis in the grave-digger scene, A Startling Effect, Chapter 7. Right: Joey's final rendition of "Hot Codlins" as his farewell to the stage, in The last Song (Chapter 25, 1828-1836). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Frow, Gerald. Oh Yes it is!: History of Pantomime. London: BBC, 1985.

Grimaldi, Joseph, and Charles Dickens. Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi, Edited By 'Boz'. With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank. London: George Routledge and Sons. The Broadway, Ludgate. New York: 416, Broome Street, 1869.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kitton, Frederic G. The Minor Writings of Charles Dickens: A Bibliography and a Sketch. London: Elliot Stock, 1900.

Macqueen-Pope, W. "The Rise and Fall of the Pantomime Harlequinade." It's Behind You. Illustrated by Illingworth. Daily Mail Annual for Boys and Girls, ed. Susan French. Christmas edition, 1954. http://www.its-behind-you.com/dailymail.html

Schlicke, Paul. "Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi." Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. P. 374.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Last modified 11 June 2017