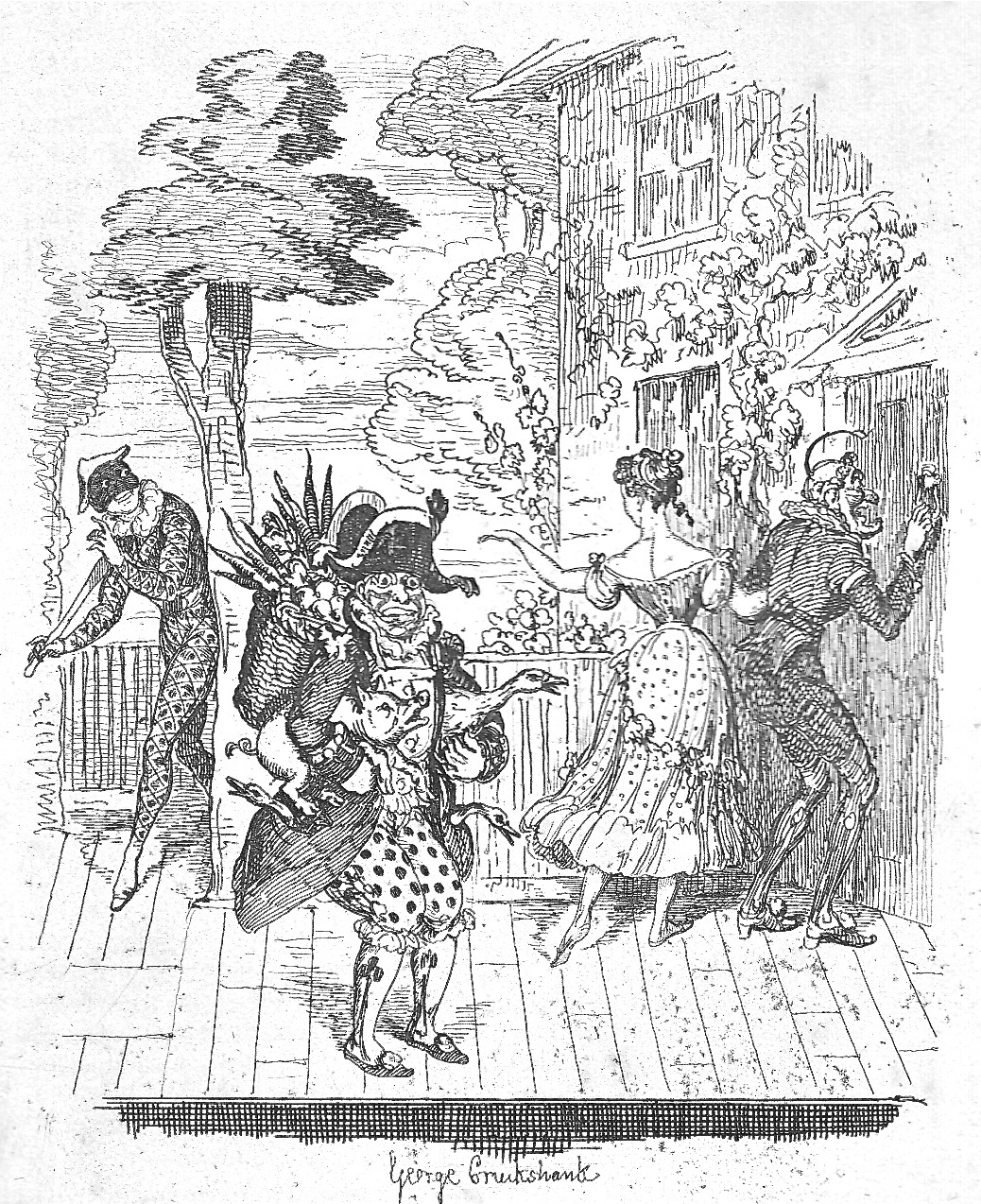

The last Song

George Cruikshank, 1792-1878

1838

Etching on copper

10.6 x 7.9 cm, vignetted

Facing page 245 in Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Edited by "Boz." With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

The last Song

George Cruikshank, 1792-1878

1838

Etching on copper

10.6 x 7.9 cm, vignetted

Facing page 245 in Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Edited by "Boz." With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

It was greatly in favour of the benefit, that Covent Garden had closed the night before; the pit and galleries were completely filled in less than half an hour after opening the doors, the boxes were very good from the first, and at half-price were as crowded as the other parts of the house. In the last piece Grimaldi acted one scene, but being wholly unable to stand, went through it seated upon a chair. Even in this distressing condition he retained enough of his old humour to succeed in calling down repeated shouts of merriment and laughter. The song, too, in theatrical language, "went" as well as ever; and at length, when the pantomime approached its termination, he made his appearance before the audience in his private dress, amidst thunders of applause. As soon as silence could be obtained, and he could muster up sufficient courage to speak, he advanced to the foot-lights, and delivered, as well as his emotions would permit, the following Farewell Address. —

"Ladies and Gentlemen: — In putting off the clown's garment, allow me to drop also the clown's taciturnity, and address you in a few parting sentences. I entered early on this course of life, and leave it prematurely. Eight-and-forty years only have passed over my head — but I am going as fast down the hill of life as that older Joe — John Anderson. Like vaulting ambition, I have overleaped myself, and pay the penalty in an advanced old age. If I have now any aptitude for tumbling, it is through bodily infirmity, for I am worse on my feet than I used to be on my head. It is four years since I jumped my last jump — filched my last oyster — boiled my last sausage — and set in for retirement. Not quite so well provided for, I must acknowledge, as in the days of my clownship, for then, I dare say, some of you remember, I used to have a fowl in one pocket and sauce for it in the other.

"To-night has seen me assume the motley for a short time — it clung to my skin as I took it off, and the old cap and bells rang mournfully as I quitted them for ever.

"With the same respectful feelings as ever do I find myself in your presence — in the presence of my last audience — this kindly assemblage so happily contradicting the adage that a favourite has no friends. For the benevolence that brought you hither — accept, ladies and gentlemen, my warmest and most grateful thanks, and believe, that of one and all, Joseph Grimaldi takes a double leave, with a farewell on his lips, and a tear in his eyes.

"Farewell! That you and yours may ever enjoy that greatest earthly good — health, is the sincere wish of your faithful and obliged servant. God bless you all!"— Chapter XXV. "1828 to 1836, The farewell benefit at Drury Lane, — Grimaldi's last appearance and parting address — The Drury Lane Theatrical Fund, and its prompt reply to his communication — Miserable career and death of his son — His wife dies, and he returns from Woolwich (whither he had previously removed) to London— His retirement," pp. 244-45.

Grimaldi spent the last years of his life living alone in Southampton Street, Islington, before he was found dead in his bed by his housekeeper on 1st June, 1837. He was buried in St. James's churchyard, Pentonville, on 5th June, 1837 — the area is now Joseph Grimaldi Park and features, as well as his grave, a coffin-shaped memorial . . . that plays musical notes when danced upon (it's apparently possible to play his signature song, "Hot Codlins" when "dancing upon his grave"). — Exploring London.

A little old woman a living she got, By selling hot codlins, hot! hot! hot! And this little old woman who codlins sold, Though her codlins were hot, thought she felt herself cold, So to keep herself warm, she thought it no sin, To fetch for herself a quartern of — Ri, tol, lol, &c.

This little old woman set off in a trot, To fetch her a quartern of hot! hot! hot! She swallowed one glass, and it was so nice, She tipp'd off another in a trice; The glass she fill'd till the bottle shrunk, And this little woman they say got — Ri, tol, lol, &c.

This little old woman, while muzzy she got, Some boys stole her codlins, hot! hot! hot! Powder under her pan put, and in it some stones, [usually: "round stones"] Says the little old woman, "these apples have bones!" The powder the pan in her face did send, Which sent the old woman on her latter — Ri, tol, lol, &c.

The little old woman then up she got, All in a fury, hot! hot! hot! Says she, "Such boys, sure, never were known, They never will let an old woman alone." Now here is my moral, around let it buz — If you wish to sell codlins, never get [muzzed] — Ri, tol, lol, &c. — "Tune Req: Hot Codlings" http://www.mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=139901

Although the song caught on late in Joey Grimaldi's career, when he performed it in the Dibdin pantomime entitled The Talking Bird, he probably first performed it at Christmas 1806 in Harlequin Mother Goose, a panto written by Charles Dibdin. It enjoyed a revival under music hall comic Tony Pastor in the 1860s. The song has always been an exercise in audience participation:

Joey invited his audience to complete the last line, inviting a dialogue in which the knowing spectators would subvert the performance by calling out "Gin," cueing him to adopt a tone of soulful disappointment, declaring "Oh for shame!" in complicit response. — The Gentle Author.

Seated before the footlights because he was unable to stand any length of time, and obviously on intimate terms with members of the orchestra immediately before him, Grimaldi performed briefly in the benefit which the management of Drury Lane had arranged for him on 27 June 1828, having already made his farewell appearance at Sadler's Wells on 17 March. As a treat for his devoted followers, he assailed one final time the comic song that had won him a place in the hearts of all Londoners, "Hot Codlins," the cry of an old, gin-addicted woman hawking roasted apples in the streets of Pentonville: "A little old woman, her living she got by selling codlins, hot, hot, hot." In the Cruikshank illustration, Grimaldi in his regular clown's costume and makeup is apparently reading from a small book and he points out into the audience. The men in the orchestra are laughing heartily at whatever witticism or anecdote the great clown is retailing. In the boxes (upper left) fashionably-dressed men and women with at least one child are smiling, and backstage, behind the practicable door (centre) actors and actresses look on admiringly.

In the end, Joey's success led to his self-destruction through a relentless performance schedule, often playing two theatres on the same night and enacting demanding physical stunts. By the age of forty-eight, he was unable to continue, and his departure from the stage and farewell to his adoring audience must rank as one of the most emotional in British theatre history. — The Gentle Author.

He subsequently received a pension of £100 a year from the Drury Lane Theatrical Fund; this he collected for nine years. Severely disabled, Grimaldi spent his last years beside the fireplace of 'The Marquis of Cornwallis' tavern, in Pentonville, from which each night the landlord, George Cook, would carry the old clown home on his back.

On Monday, 17 March 1828, he took a benefit at Sadler's Wells, and made his last appearance in public. On 27 June of the same year, at Drury Lane, he took a second benefit, and made his last appearance in public. On this occasion he played a scene as Harlequin Hoax, seated through weakness on a chair, sang a song, and delivered a short speech.His second wife died in 1835, and on 31 May 1837 he died in Southampton Street, Pentonville. — Sir Leslie Stephen and Peter Lee (1890), p. 215.

"Grimaldi is dead and hath left no peer" said the London Illustrated News. It continued "We fear with him the spirit of pantomime has disappeared". "The Garrick of Clowns" was buried in the courtyard of St. James's Chapel, Pentonville.

Charles Dickens, who put Grimaldi's memoirs in order said "the clown left the stage with Grimaldi, and though often heard of, has never since been seen." — Roadshows: The Magic of Theatre; The Magic of Pantomime

His tombstone, now in Grimaldi Park, Pentonville, reads:

Sacred To the Memory of Mr. Joseph Grimaldi, Who departed this life, May 31st, 1837, Aged fifty-eight years — "Concluding Chapter," p. 254.

However, the last word should go to the great Grimaldi himself. On the 18 December 1836 he penned the following elegy:

Life is a game we are bound to play — The wise enjoy it, fools grow sick of it;Losers, we find, have the stakes to pay, That winners may laugh, for that's the trick of it. "J. Grimaldi." — Chapter 25, 1828 to 1836, p. 252.

Left: George Cruikshank's depiction of a childhood scare, as Joey's father throws the lad (dressed as a monkey) towards the audience and the tether breaks, in Joe's debut into the Pit at Sadler's Wells in Chapter 1. Centre: Cruikshank's depiction of Joey working with animals, always a tricky practice on stage: Live Properties, Chapter 15. Right: Joey's recollection of John Philip Kemble's chastising Davis as the gravedigger in Hamlet, in A Startling Effect (Chapter 7, 1798 to 1801). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Artful Dodger. "Tune Req: Hot Codlings." 26 Aug 11 2016 http://www.mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=139901.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxfiord: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Dickens, Charles. Sketches by Boz; Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890.

"Famous Londoners — Joey Grimaldi." Exploring London. 8 February 2016. https://exploring-london.com/2016/02/08/famous-londoners-joseph-grimaldi/

The Gentle Author, "Joseph Grimaldi, Clown."Spitalfield's Life. 5 February 2012. http://spitalfieldslife.com/2012/02/05/joseph-grimaldi-clown/

Grimaldi, Joseph, and Charles Dickens. Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi, Edited By 'Boz'. With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank. London: George Routledge and Sons. The Broadway, Ludgate. New York: 416, Broome Street, 1869.

"Joseph Grimaldi." Roadshows: The Magic of Theatre; The Magic of Pantomime. http://www.its-behind-you.com/grimaldi.html

Hartnoll, Phyllis (ed.). The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1972; rpt., 1987.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kitton, Frederic G. The Minor Writings of Charles Dickens: A Bibliography and a Sketch. London: Elliot Stock, 1900.

Knight, John Joseph. Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900. Volume 23; https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Grimaldi,_Joseph_(DNB00)

Schlicke, Paul. "Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. P. 374.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Stephen, Leslie, and Peter Lee. "Grimaldi, Joseph (1779-1837)." Dictionary of National Biography. 1890. P. 250-251.

Thornbury, Walter. Chapter 35, "Pentonville." Old and New London. Vol. 2. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878. British History Online. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol2

Last modified 12 June 2017