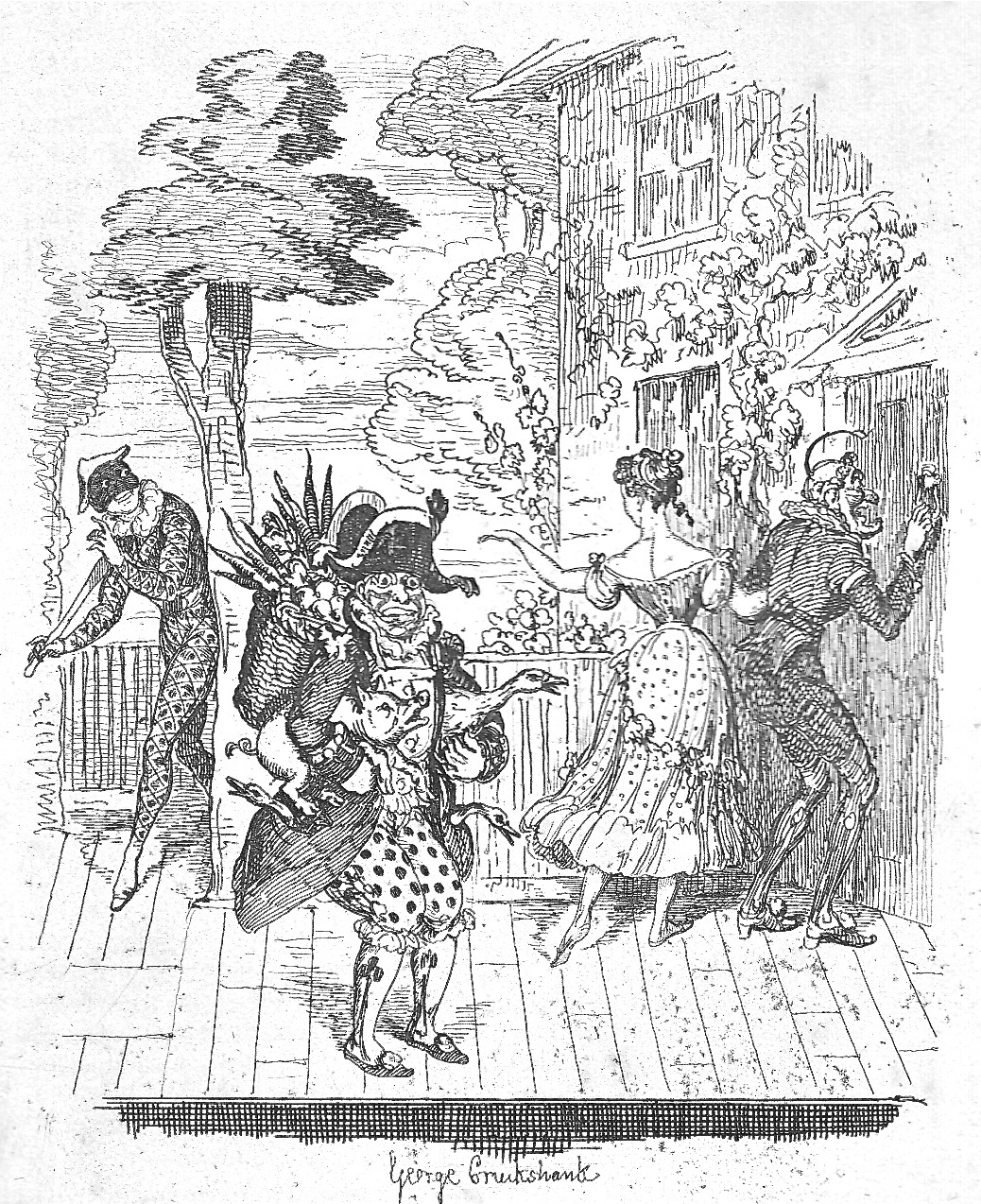

A Startling Effect.

George Cruikshank, 1792-1878

1838

Etching on copper

11 x 8.3 cm

Facing page 83 in Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Edited by "Boz." With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> George Cruikshank —> Next]

A Startling Effect.

George Cruikshank, 1792-1878

1838

Etching on copper

11 x 8.3 cm

Facing page 83 in Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Edited by "Boz." With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

As before, all went well till the grave-diggers' scene commenced; when Kemble, while waiting for his "cue" to go on, listened bodingly to the roars of laughter which greeted the colloquy of Davis and his companion. At length he entered, and at the same moment, Davis having manufactured a grotesque visage, was received with a shout of laughter, which greatly tended to excite the anger of "King John." His first words were spoken, but failed to make any impression: and upon turning towards Davis, he discovered that worthy standing in the grave, displaying a series of highly unsuitable although richly comic grimaces.

In an instant all Kemble's good temper vanished, and stamping furiously upon the stage, he expressed his anger and indignation in a muttered exclamation, closely resembling an oath. This ebullition of momentary excitement produced an odd and unexpected effect. No sooner did Davis hear the exclamation and the loud stamping of the angry actor, than he instantly raised his hands above his head in mock terror, and, clasping them together as if he were horrified by some dreadful spectacle, threw into his face an expression of intense terror, and uttered a frightful cry, half shout and half scream, which electrified his hearers. Having done this, he very coolly laid himself flat down in the grave, (of course disappearing from the view of the audience), nor could any entreaties prevail upon him to emerge from it, or to repeat one word more. The scene was done as well as it could be, without a grave-digger, and the audience, while it was proceeding, loudly expressed their apprehensions from time to time, "that some accident had happened to Mr. Davis." — Chapter VII. 1798 to 1801. "Partiality of George the Third for Theatrical Entertainments — Sheridan's kindness to Grimaldi — His domestic affliction and severe distress — The production of Harlequin Amulet a new era in Pantomime — Pigeon-fancying and Wagering — His first Provincial Excursion with Mrs. Baker, the eccentric Manageress — John Kemble and Jew Davis, with a new reading — Increased success at Maidstone and Canterbury — Polite interview with John Kemble," p. 82-83.

Once more, Cruikshank has realised a theatrical scene, but the picture is not of a pantomime, the Grimaldi specialty, but of a provincial production of The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark starring the early nineteenth-century Shakespearean actor-manager John Philip Kemble (1 February 1757 — 26 February 1823), whose company toured through northern England in 1780-81, although this chapter is set at the end of that decade. He débuted as Hamlet in Dublin on 2 November 1781, and in the same role on the stage of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, on 30 September 1783, although it was his performance there as Macbeth alongside his talented sister, Sarah Siddons, on 31 March 1785 that made him a popular favourite. Grimaldi's terming John Philip Kemble "King John" merely suggests that the reminiscence post-dates his playing that role when he and his sister had first appeared together at Drury Lane on 22 November 1783, as Beverley and Mrs. Beverley in Edward Moore's The Gamester and, in the same bill, and as King John and Constance in Shakespeare's tragedy.

The Gravedigger's Scene was popular in Victorian art, and its theatrical presentation satirized in Dickens's Great Expectations. One receives a sense from Cruikshank's illustration and Grimaldi's anecdote of the difficulties that legitimate actors encountered in presenting Shakespeare in the provinces, and of the tension between actors of licensed drama and those who worked in the minor theatres. John Philip Kemble was the greatest actor of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century British stage following the death of David Garrick in 1779. Coming from a theatrical family, for more twenty-five years "England's foremost theatrical dynasty" (Southern, 106) which included his sister, the sublime Sarah Siddons (1775-1831), in an era in which extensive rehearsal was uncommon,

Kemble made at least some effort to introduce greater discipline and precision in the conduct of rehearsals. Because he insisted on such essentials as promptness, he gained a reputation for 'uncommon asperity'. He objected strongly to the neglect of smaller parts, and secondary players were required to perform their roles exactly as rehearsed. — Richard Southern, p. 114.

Hence, Kemble is furious at Davis for introducing business not worked on in rehearsal, and in the process stealing the scene. Cruikshank captures effectively Kemble's stately, tall, and imposing figure, impressive countenance, and grave, solemn demeanour — and his indignation at Davis's tomfoolery as the gravedigger. The mixed-gender audience, a solidly middle-class group of half-a-dozen men, five women, and a number of children, seated in the stalls, appear to be laughing at Davis's over-the-top gestures and facial expression. The perspective is that of an audience member sitting well back in the middle of the seats in the house, and Cruikshank has as it were cropped the composition so that we do not see the side-curtains. The "effect," that is the contrast between the serious, black-cloaked Prince in his plumed hat and the long-faced comedian in white is as much highly amusing to the audience as "startling." The provincial audience sit on benches very close to the stage, immediately behind the limited orchestra (suggested by the cello to the right). The elaborate stage set with a gothic church, trees, a tomb in the middle ground, and tombstones in the distance is consistent with the picturesque practices of the Romantic era. The open trapdoor which serves as Ophelia's grave is well forward, and the skull of Yorick is by Hamlet's upstage leg. In modern film productions, two "clowns" (often with renowned comic backgrounds) play the parts of the first and second gravediggers, but Cruikshank implies that Kemble made do with one, placing heavier demands upon the single comedian playing the grave-digger.

One receives a sense from Cruikshank's illustration of the difficulties that legitimate actors had with presenting Shakespeare in the provinces. With a stately mien and gravely serious demeanour, Kemble brought something of his seminary training to such roles as Brutus and Coriolanus, but perhaps lacked the subtle sense of humour necessary for a convincing portrayal of Hamlet. Nevertheless, with his powers of declamation and attention to production details, he is associated along with his younger Charles in the nineteenth-century's Shakespeare revival. In 1800 Grimaldi took the role of the Second Gravedigger in Hamlet, alongside John Philip Kemble's Prince of Denmark, at Drury Lane. As Grimaldi implies, the relationship between Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the proprietor of the theatre, and the actor-manager was sufficiently tenuous that Kemble withdrew from his position of manager at Drury Lane. Although he resumed his duties at the beginning of the season 1800-1801, at the close of 1802 he finally resigned connection with it and became manager of Covent Garden, in which he had acquired a sixth share. Thus, it would appear that Grimaldi's dating the incident to the period of 1798-1801 is faulty, as the provincial tour was much earlier — in 1778, Kemble joined the York company of Tate Wilkinson. However, one may relate the anecdote to Sir Thomas Lawrence's exhibiting the gigantic canvas of Kemble as Hamlet in the gravedigger scene at the Academy in 1801, the most famous of four huge canvases which Lawrence painted showing Kemble in various dramatic roles (height: 61 cm estimate, width: 45.5 cm estimate), probably painted in 1798 or 1799. From the earlier period comes this review of Kemble in the role of Hamlet:

I went, as I promised, to see the new ‘Hamlet’, whose provincial fame had excited your curiosity as well as mine. There has not been such a first appearance since yours: yet Nature, though she has been bountiful to him in figure and feature, has denied him voice; of course he could not exemplify his own direction for the players to 'speak the speech trippingly on the tongue', and now and then he was as deliberate in his delivery as if he had been reading prayers, and had waited for the response. He is a very handsome man, almost tall and almost large, with features of a sensible but fixed and tragic cast; his action is graceful, though somewhat formal, which you will find it hard to believe, yet it is true. Very careful study appears in all he says and all he does; but there is more singularity and ingenuity, than simplicity and fire. Upon the whole he strikes me rather as a finished French performer, than as a varied and vigorous English actor, and it is plain he will succeed better in heroic, than in natural and passionate tragedy. Excepting in serious parts, I suppose he will never put on the sock. You have been so long without a 'brother near the throne' that it will perhaps be serviceable to you to be obliged to bestir yourself in Hamlet, Macbeth, Lord Townley and Maskwell; but in Lear, Richard, Falstaff and Benedict you have nothing to fear . . . . — Richard Sharp, 1785.

When the Covent Garden playhouse burned down on 20 September 1808, Kemble suffered financially. Challenged for theatrical supremacy by the rising tragedian Edmund Kean, he retired to the European continent after his last performance as Coriolanus on 23 June 1817, and died in Lausanne, Switzerland, six years later. The Kembles continued, however, to exert considerable influence over the stage afterward as Fanny Kemble, John's daughter, continued her illustrious career and John Kemble, the younger brother, retired from the stage to become the Examiner of Plays in the Office of the Lord Chamberlain in 1836, in which role he acted as theatrical censor.

Having achieved overnight celebrity status with his virtuoso comic performance in the original production of Mother Goose, a production that made record profits among nineteenth-century British pantomimes, Grimaldi won national recognition, earned henceforth enormous fees, and entered a social circle that included such early nineteenth-century luminaries as the great poet and playboy Lord Byron, the gifted tragic actress Sarah Siddons, stage giant Edmund Kean, popular Gothic novelist Matthew 'Monk' Lewis, and the entire Kemble family. However, in recalling this incident Grimaldi seems to side with the burlesque comedian, Davis, in terms of the comedian's upstaging "King John." Significantly, this is the only illustration in which Joey Grimaldi himself does not actually appear, but the anecdote illustrated demonstrates the writer's familiarity with the leading figures of the Regency stage, John Philip Kemble and Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

Left: George Cruikshank's depiction of a childhood scare, as Joey's father throws the lad (dressed as a monkey) towards the audience and the tether breaks, in Joe's debut into the Pit at Sadler's Wells in Chapter 1. Centre: Cruikshank's depiction of Joey working with animals, always a tricky practice on stage: Live Properties, Chapter 15. Right: Joey's final rendition of "Hot Codlins" as his farewell to the stage, in The last Song (Chapter 25, 1828-1836). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Ashton, Geoffrey. "John Philip Kemble as Hamlet in Hamlet by William Shakespeare," after Sir Thomas Lawrence, after 1798. Catalogue of Paintings at the Theatre Museum, London. Ed. James Fowler. London : Victoria and Albert Museum, 1992.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxfiord: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Grimaldi, Joseph, and Charles Dickens. Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi, Edited By 'Boz'. With ten illustrations by George Cruikshank. London: George Routledge and Sons. The Broadway, Ludgate. New York: 416, Broome Street, 1869.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kitton, Frederic G. The Minor Writings of Charles Dickens: A Bibliography and a Sketch. London: Elliot Stock, 1900.

"Obituary. Mr. Charles Kemble." The Gentleman's Magazine. January 1855. Vol. 197, pp. 94-96. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.79255359;view=1up;seq=102.

Schlicke, Paul. "Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi. Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. P. 374.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Sharp, Richard. Letters and Essays in Prose and Verse. London: Moxon: 1834.

Southern, Richard. "'The Kemble Religion': 1776-1812." The Revels History of Drama, Volume Six: 1750-1880. London: Methuen, 1975. pp. 106-121.

Last modified 8 June 2017