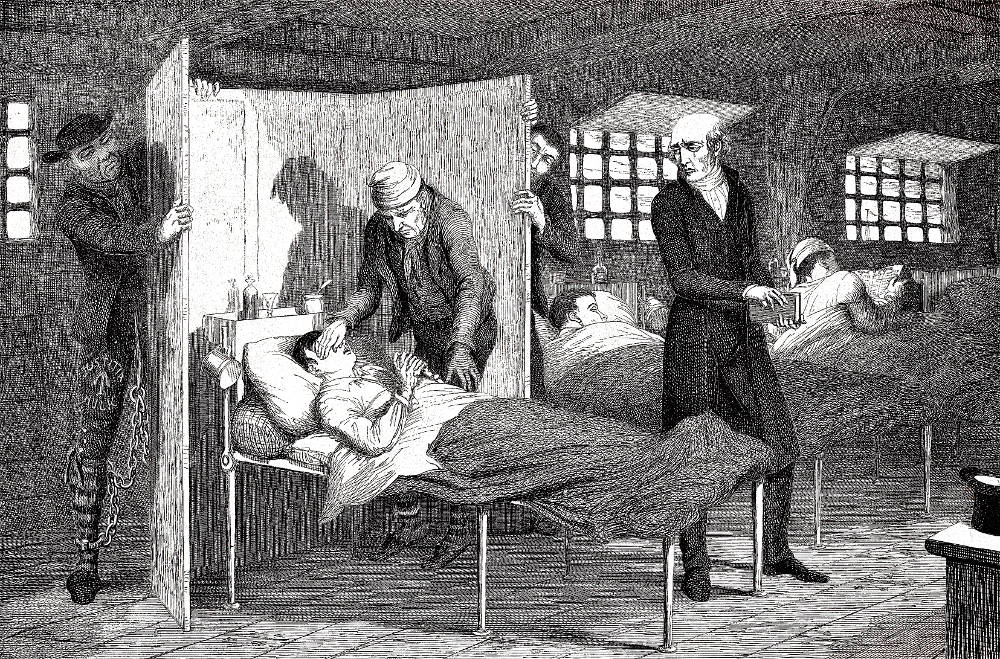

Early Dissipation Has Destroyed the Neglected Boy. — The Wretched Convict Droops and Dies. — George Cruikshank. 1848. Seventh illustration in The Drunkard's Children. Folio page: 46 x 36 cm (24 inches by 14.5 inches), framed. Cruikshank reproduced the etchings by glyphography, "enabling the publisher [David Bogue, London] to sell the entire series for one shilling" (Vogler, p. 159). "This suite appeared in similar size and editions to that of The Bottle, but it was never reissued in smaller format" (Vogler, p. 161), except that throughout this sequel the majority of the scenes bear no signature. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary for Plate VII: Death aboard a "Hulk"

Attended only by the infirmary physician, the institutional chaplain, and several convicts who are serving as medics, the Drunkard’s son dies of a fever aboard a prison hulk. The activity of the four figures around the boy's bed implies that the young thief has just passed away: The shipboard physician is just closing the boy’s eyes as the chaplain, having read the last rites, closes his Bible or Anglican Book of Common Prayer with an air of finality. Wilfred Hugh Chesson judged this illustration "a masterpiece" because "the shadow that the prison doctor casts on the screen which two convicts draw around the bed is, in effect, a creature to startle us" (p. 57). While the manacled infirmary attendant and his co-worker place a screen around the dead teenager's bed, the two other patients express no concern about the fact that one of their number has just died — one is asleep, and the other, with head bandaged, is attempting to read in the dim light. Richard A. Vogler curtly remarks of their apparent indifference, "As in Bruegel's painting The Fall of Icarus and W. H. Auden's famous poem interpreting it, human tragedy makes little impact on the way of the world" (p. 162). Cruikshank suggests that such deaths from fever were all too common, and that all too often convicted felons never arrived at the "place beyond the seas" to which the system had sentenced them. The illustrator offers no particular fatal malady, although the caption attributes the teenager's death to the consequences of "Early Dissipation," by which Cruikshank would have us understand "juvenile alcoholism." Since such temporary prison facilities had poor ventilation and sanitation, the Drunkard's son has likely just died of typhus or cholera.

In The Drunkard's Children provides a series of tableaux to narrate the son and daughter's initiation into the seamier side of London entertainments and their descent into crime and punishment. Cruikshank transports us from a scene of thirty or more drinkers crammed together in the gin-palace, twenty gamblers and roisters in the beer-shop, another twenty imbibers and dancers in the dance-hall, to a mere eight sleepers aroused in lodging-house. In the sixth plate, the artist isolates for examination the son and the daughter, arraigned for larceny in their Central Criminal Court trial at London's Old Bailey, in which thirty-four lawyers, jurymen, and spectators largely ignore the plight of the Drunkard's children. Continuing the visual progression from dubious companionship (crowded drinking scenes) towards pathetic alienation and death, in Plate VI (The Drunkard's Son is Sentenced to Transportation for Life; The Daughter, Suspected of Participation in the Robbery, Is Acquitted. — The Brother and Sister Part For Ever in This World), Cruikshank had provided a single, callous witness to their suffering. The boy's seventh and final appearance here derives intensity from his inertness as well as from the spartan features of the room and the limited cast of characters and — the convict serving as a medical assistant, the ship's doctor (closing the boy's eyes), a second assistant, the grim-faced chaplain, two disinterested patients, the simple, wrought-iron-framed beds, the bare planks, and the three barred portholes. The clergyman with the extensive forehead (suggestive of spirituality) mournfully regards this latest victim of the system who Cruikshank would convince us is another victim of gin. In the courtroom scene, nobody had regarded the brother and sister with compassion, but here and in the final illustration, in marked contrast, (albeit too late) sympathetic observers (the minister and the middle-class couple on the bridge) express concern over the fates of the Drunkard's children. The girl's death will perhaps figure in the local papers as the suicide of a prostitute; the boy's death will appear in the surgeon's log of the hulk Justitia.

The terms "prison hulk" and "convict ship" should therefore not be regarded as wholly synonymous since a "hulk" was incapable of going to sea, whereas the government could contract a seaworthy vessel to transport felons from their place of conviction to their place of banishment. The Cruikshank illustration in fact identifies a specific "hulk" as the setting, since "Justitia Hulk" on the medical attendant's penal uniform alludes to a particular vessel which was run by a government transportation contractor named Duncan Campbell in the County of Middlesex. "The first civilian prison hulk, was an ex-convict transport ship of Campbell's called the Justitia and soon after, a further 50 or more were brought into service until 1850" ("Nineteenth-Century Prison Ships"). Cruikshank may be exploiting thename of the vessel not merely as a topical allusion, but for its ironic value as the system that has placed the Drunkard's son aboard the disease-prone vessel is anything but just to young offenders.

In the year prior Cruikshank's publishing The Drunkard's Children, the state had attempted to distinguish between child criminals, young offenders, and hardened criminals by passing the Juvenile Offenders Act (10 & 11 Victoria, c. 82), so that a magistrate could, at his discretion, discharge an offender under the age of 14 if the charge were petty larceny. Cruikshank does not specify the nature of the son's offence, which apparently involves "a Desperate Robbery" (Plate IV), but not necessarily murder. In the first series, the son appears as a teenager or young adult in the final illustration, so that, by the time that the system indicts him, he is beyond the age at which a magistrate might under the terms of the new statute exercise summary disposition and discharge the accused without any punishment. Now, having received the sentence of "Transportation for Life," theson meets a pathetic end. All that remains for Cruikshank to do in order to fulfill thealmost-biblical curse on the Drunkard's family is to stage the daughter's suicide. In contrast to the son's passively awaiting death in the infirmary, Cruikshank depicts her in a kind of dance of death that balances her dancing the polka among a happy throng of young proletarians in the third illustration, From the Gin Shop to the Dancing Rooms, from the Dancing Rooms to the Gin Shop, the Poor Girl is Driven on in That Course Which Ends in Misery.

Cruikshank's final two illustrations reflect the concerns of vocal advocates of prison reform such as John Howard, Sir William Blackstone, and Hepworth Dixon, who had attacked sentences of transportation for relatively minor offences as essentially unjust since the system treated first-time offenders and career criminals in precisely the same way. Within five years of Cruikshank's consigning the Drunkard's son to Australian transportation, the British government had abolished the sentence for first-time offenders, although the last convict ship, the Hougoumont docked at Fremantle, Western Australia, on 9 January 1868, with sixty-two convicted Fenian political and military prisoners, transported for their part in the uprising of 1867.

Relevant illustrations of other deathbed scenes, 1841-1869

Left: The most famous child's death in Victorian literature, George Cattermole's engraving, which influenced later illustrators, At Rest (Nell dead) in The Old Curiosity Shop (30 January 1840). Centre: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's lacrimose family bid the drunkard-father farewell in Dickens's sketch The Drunkard's Death (1864). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s sentimental realisation of the imagined death of Bob Crachit's son, 'Poor Tiny Tim!' in the Ticknor-Fields' A Christmas Carol (1869). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Whereas Phiz makes light of the conventional deathbed scene in I find Mr. Barkis "going out with the tide" in the serialised David Copperfield (February 1850), Victorian illustrators tend to treat the deaths of innocents with grave seriousness. Although Barkis's is the second significant death in David's life, it is the first death that Dickens's narrator, David, experiences as an adult, and he responds according to conventional middle-class decorum. As is the case with the death of little Paul Dombey and Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop,nineteenth-century novelists often describe the deathbed scene with profound, overly sentimental religiosity, evident in such scenes as Darley's The Drunkard's Death (1864), which focuses on the heart-felt grief of the deceased's family. In The Drunkard's Children Cruikshank makes the boy's premature death pathetic by his sheer isolation from such grieving observers, for, unlike Darley, he treats the deathbed scene with rigorous and unemotional realism, in contrast to the usual Victorian sentimentality in such scenes.

Related Material

- "Transported for Life" in Cruikshank and Dickens (1848, 1861)

- Transportation as Judicial Punishment in Nineteenth-Century Britain

- The Cornhill, Great Expectations, and The Convict System in Nineteenth-Century England

- Great Expectations. Magwitch, and Australia: A Bibliography

- Crime in Victorian England

- A Pickpocket in Custody (1839)

- "What is this?" inquired one of the magistrates. — "A pick-pocketing case, Your Worship."

- The Old Bailey

- The Punishment of Convicts in Nineteenth-Century England

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

Bibliography

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. The Drunkard's Children. A Sequel to "The Bottle." London: David Bogue, 1848.

Harvey, John. "George Cruikshank: A Master of the Poetic Use of Line." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 129-156.

"Introduction — Nineteenth-Century Prison Ships." The National Archives. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/19th-century-prison-ships/#introduction

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Meisel, Martin. Chapter 7, "From Hogarth to Cruikshank." Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1989. Pp. 97-141.

Mellby, Julie L. "More than 100,000 copies sold in the first few days." Graphic Arts: Exhibitions, acquisitions, and other highlights from the Graphic Arts Collection, Princeton University Library. Web. 13 April 2011. https://blogs.princeton.edu/graphicarts/2011/04/the_bottle.html

Paroissien, David. The Companion to 'Great Expectations'. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2000.

Richardson, Betty. "Prisons and Prison Reform." Victorian Britain, An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Pp. 638-41.

"Sentencing to Departure - Prison Hulks & Convict Gaols." Victorian Crime and Punishment. http://vcp.e2bn.org/justice/page11382-sentencing-to-departure-prison-hulks-convict-gaols.html

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Williams, Tony. "Over the Seas and Far Away, or the English Gulag — Transportation and the Hulks." The Dickens Magazine. (2000) Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 8-9.

Last modified 9 September 2017