Prisoners sentenced to transportation for life were read the following verdict: 'It is therefore ordered and adjudged by this court Court, that you be transported upon the seas, beyond the seas, to such a place as His Majesty, by the advice of His Privy Council, shall think fit to direct and appoint, for the term of your natural life’ — Robert Hughes quoted by David Paroissien

espite Dickens's use of a hulk in the opening chapters of his 1861 novel Great Expectations and his having convicted felon Abel Magwitch return from a life sentence, the British government ceased to employ hulks on the final expiry of the 1776 Act in 1857, fully four years before Dickens published the novel. The hulks were not, however, an anachronism when Cruikshank developed the sixth and seventh plates of The Drunkard's Children. Just the year previous, the state had attempted to distinguish between child criminals, young offenders, and hardened criminals by passing the Juvenile Offenders Act (10 & 11 Victoria, c. 82), so that a magistrate could, at his discretion, discharge an offender under the age of 14 if the charge were larceny without violence. Cruikshank does not specify the nature of the son's offence, which apparently involves "a Desperate Robbery" (Plate IV), but not necessarily murder. In the first series, The Bottle, Cruikshank describes the son as a mere child until the final illustration, in which he appears to be a teenager, so that, by the time he is indicted for larceny, he is beyond the magistrate's being allowed by the new statute to exercise summary disposition and discharge the boy without any punishment.

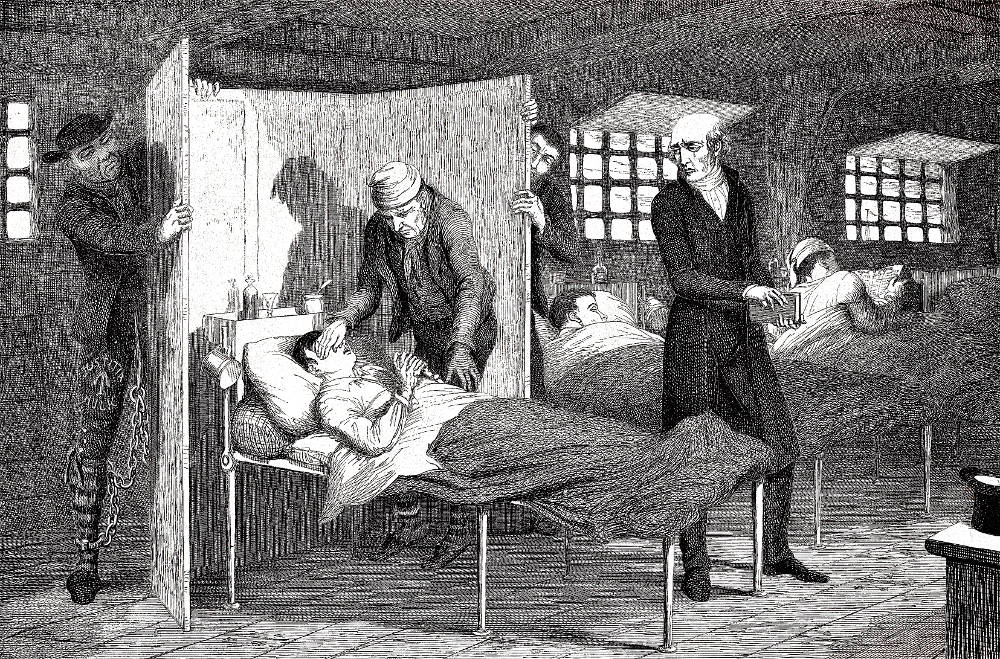

After all the lively crowd scenes suggestive of the young criminal's revelling in the proletarian culture of London to the point of self-destruction — the gin-palace, beer-shop, dance-hall, lodging-house, and Old Bailey criminal court trial, the boy's final appearances in George Cruikshank's The Drunkard's Children (1848) gain intensity from the small cast of characters and the spartan features of each of the rooms — the visiting room of the prison and the infirmary on the hulk where the young man, convicted of larceny, dies. The boy's death will be recorded in the surgeon's log, the girl's as yet another prostitute who committed suicide in the local papers.

In trying to understand how the Drunkard's son, although a first-time offender, can be sentenced to life transportation for a robbery, the viewer realizes that Cruikshank is struggling to have the viewer continue to sympathize with the Drunkard's children. Consequently, the artist mitigates the larceny that the boy has committed by not adding a murder charge, even though by this point in history the boy's crime would not have merited a life sentence unless it involved a capital offense such as murder. The final scenes in the 1848 sequence demonstrate the flimsiness of Cruikshank's contention that alcoholism causes parental neglect, and thereby turns an alcoholic's children into criminals. As Harry Stone remarks of this critical issue that divided Dickens and Cruikshank, “the origins of poverty and crime, the intricate gestation of neglectful or rejecting parents, the ravaging inception of ignorance, cruelty, and despair — all these and more, in the gospel of Cruikshank, were simply by-products of strong drinks” (p. 236).

By the time that Cruikshank composed The Drunkard's Children in the late 1840s, being a "returned transport" was no longer a capital crime: the last convicted felon to face the death penalty for returning "from Australia was hanged in 1810, and the offence had not been a capital one since 1835" (Tony Williams, p. 8). In every way, then, Cruikshank has made his young protagonist the subject of an inflexible inhumane, antiquated system: sentenced to life transportation for robbery, he dies (probably of typhus or cholera, but perhaps of cirrhosis of the liver) aboard a hulk, and never gets to see Australian shores.

Pertinent Cruikshank Illustrations from The Drunkard's Children (1848)

Left: Cruikshank's highly realistic description of the Criminal Court in the Old Bailey, From the Bar of the Gin Shop to the Bar of the Old Bailey It Is But One Step. Right: Cruikshank's sympathetic portrayal of the convicted felon's bidding the sole surviving member of his family farewell, The Drunkard's Son is Sentenced to Transportation for Life; The Daughter, Suspected of Participation in the Robbery, Is Acquitted. — The Brother and Sister Part For Ever in This World. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Cruikshank's pathetic realisation of the young convict's dying of fever aboard a temporary holding facility, Early Dissipation Has Destroyed the Neglected Boy. — The Wretched Convict Droops and Dies. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Related Material

- Transportation as Judicial Punishment in Nineteenth-Century Britain

- The Parliamentary Report on Transportation (1838)

- The Cornhill, Great Expectations, and The Convict System in Nineteenth-Century England

- Great Expectations. Magwitch, and Australia: A Bibliography

- Crime in Victorian England

- A Pickpocket in Custody (1839)

- "What is this?" inquired one of the magistrates. — "A pick-pocketing case, Your Worship."

- The Old Bailey

- The Punishment of Convicts in Nineteenth-Century England

- Life in Nineteenth-Century Prisons as a Context for Great Expectations

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

Bibliography

Cruikshank, George. The Drunkard's Children. A Sequel to "The Bottle." London: David Bogue, 1848.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. London: Chapman and Hall, 1861.

"Introduction — Nineteenth-Century Prison Ships." The National Archives. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/19th-century-prison-ships/#introduction

Paroissien, David. The Companion to 'Great Expectations'. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2000.

Richardson, Betty. "Prisons and Prison Reform." Victorian Britain, An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Pp. 638-41.

"Sentencing to Departure - Prison Hulks & Convict Gaols." Victorian Crime and Punishment. http://vcp.e2bn.org/justice/page11382-sentencing-to-departure-prison-hulks-convict-gaols.html

Stone, Harry. "Dickens, Cruikshank, and Fairy Tales." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 213-48.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Williams, Tony. "Over the Seas and Far Away, or the English Gulag — Transportation and the Hulks." The Dickens Magazine. 1, No. 1 (2000): 8-9.

Last modified 26 August 2017