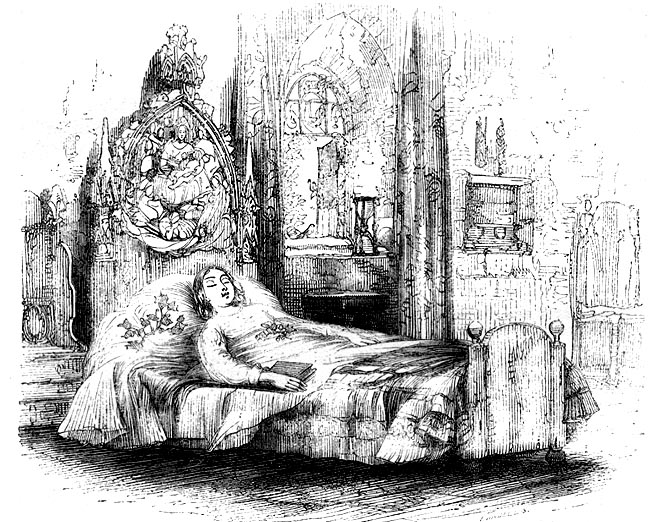

At Rest (Nell dead) by George Cattermole. 3 3/4 x 4 ½ inches (9.5 cm high by 11.8 cm wide). Wood-engraving. Chapter 71, The Old Curiosity Shop, Part 39. 30 January 1841 in serial publication (seventy-third plate in the series) in Master Humphrey's Clock, Part 42, 210. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Context of the Illustration

By little and little, the old man had drawn back towards the inner chamber, while these words were spoken. He pointed there, as he replied, with trembling lips.

"You plot among you to wean my heart from her. You never will do that — never while I have life. I have no relative or friend but her — I never had — I never will have. She is all in all to me. It is too late to part us now."

Waving them off with his hand, and calling softly to her as he went, he stole into the room. They who were left behind, drew close together, and after a few whispered words — not unbroken by emotion, or easily uttered — followed him. They moved so gently, that their footsteps made no noise; but there were sobs from among the group, and sounds of grief and mourning.

For she was dead. There, upon her little bed, she lay at rest. The solemn stillness was no marvel now.

She was dead. No sleep so beautiful and calm, so free from trace of pain, so fair to look upon. She seemed a creature fresh from the hand of God, and waiting for the breath of life; not one who had lived and suffered death.

Her couch was dressed with here and there some winter berries and green leaves, gathered in a spot she had been used to favour. "When I die, put near me something that has loved the light, and had the sky above it always." Those were her words.

She was dead. Dear, gentle, patient, noble Nell was dead. Her little bird — a poor slight thing the pressure of a finger would have crushed — was stirring nimbly in its cage; and the strong heart of its child mistress was mute and motionless for ever.

Where were the traces of her early cares, her sufferings, and fatigues? All gone. Sorrow was dead indeed in her, but peace and perfect happiness were born; imaged in her tranquil beauty and profound repose. [Chapter LXXI, 209-10]

Commentary

Cattermole's careful detailing connects the death of the virginal Nell with the Virgin and Holy Child of Catholic iconography in the ornate headboard in At Rest.

Like Henry Wallis's well-known painting The Death of Chatterton (1856) Cattermole's illustration relies on several obvious symbols to transform a picture of a dead person lying upon bed into a scene of secular martyrdom: the open window in both paintings represents the flight of the soul from the body while the emptied hourglass in the illustration, like the extinguished candle in the painting, emphasizes the end of a human life. Whereas Wallis's painting relies on Chatterton's pose to recall depositions and other examples of sacred history — a familiar device in both Northern and Italian Renaissance painting — Cattermole's illustration uses the Hogarthian (and Northern Renaissance) device of using an image of a standard religious scene within the picture space to transform it into a sacred space. The nativity scene — see detail, above — depicts Christ's entrance into human history and suggests that Little Nell has been reborn in heaven. [GPL]

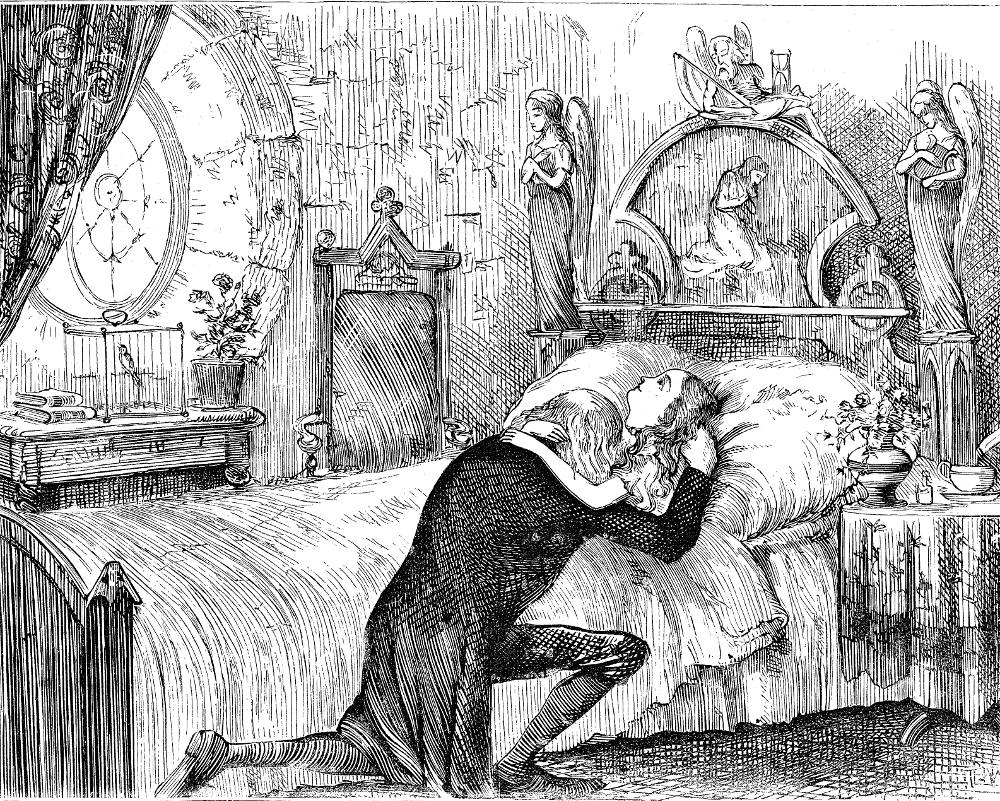

The ornate and stately The Ruin in the Snow effectively sets the mood for the climactic scene that ensues when Kit enters the ornate cottage. However, Cattermole overlooks the focal character, Kit, entirely, and focuses exclusively on the child, leaving us to guess whether she is merely sleeping, or dead, until we read the entire chapter. As Jane Rabb Cohen remarks,

Cattermole provided more effective settings than people. His first task was to portray Kit, Nell's birdcage in hand, arriving at the snow-covered parsonage (LXX, 568). According to Dickens's brief summary, a lighted window was to obscure the fact that the child lay dead inside; lacking the completed text, however, Cattermole forgot to draw the requisite curtain over the lower half of the window, though suspense is maintained because of the viewer's distance from it (fig. 121). The artist makes the parsonage the center of interest instead of Kit. Indeed, the young man, delineated from the back with parallel diagonal strokes, is visually insignificant compared to the elaborately vaulted dwelling in which Nell lies in sentimental state. But Dickens said nothing. [128]

Yet the modern viewer is unlikely to be moved even by the published print of the dead heroine with her broad, crudely delineated face, and her elaborate surroundings with their hackneyed symbols of immortality (LXXI, 575) (fig. 122). Dickens had requested the evergreens but Cattermole may have added on his own initiative the portrait of the Virgin and Child over Nell's head, the prayer book in her hand, and the open window for her departing soul with the hourglass and bird on the sill. Though the contrast between her fresh youth and her aged surroundings is stressed here as it was in Williams's picture of her first rest in the narrative [Alone in the midst of all this lumber and decay and ugly age, the beautiful child lay asleep, smiling through her light and sunny dreams], Nell herself is far less appealing in Cattermole's hands than in Williams's (I, 14).[129]

The Angelic Guides Beatrice and Nell: Two representations of The Death of Little Nell

Adina Ciugureanu points to the alternative illustration of the beatific passing of the heroine, At Rest, to show the influence of Dante on Dickens at the conclusion of The Old Curiosity Shop:

The sorrow produced by the death of Beatrice [in Dante's "Paradiso"] is similar, in its intensity, to the sorrow which Dickens's narrator described at the death of Nell and which Dickens himself felt at the death of Mary Hogarth. Both writers had visions of their ideal figures, both compared them with the Madonna, both saw them in Heaven with the angels, both imagined them as the incarnations of love. [Ciugureanu, 126]

Cattermole evokes "the spirit of Catholicism, with the crucifix on the nightstand, the image of the Virgin Mary above Nell's bed and the general impression that Nell is likened to the Virgin Mary" (127) in her sexual purity and her untrammelled innocence that has made even the itinerant thespians revere her. "Nell becomes the quintessence of purity and love through her transubstantiation from a human being to the idealistic embodiment of mother and child as one indestructible unity" (128). Nell offers her erring grandfather not only directional guidance throughout the narrative, but ultimately, after his temptation to rob Mrs. Jarley, spiritual guidance; she is, ultimately, too good for this mortal coil. She is rumoured to have consorted with angels before her death, and is now born aloft by the heavenly music of an angel's harp. "Nell's deserted place after death is obviously Heaven, where she is brought and comforted by angels. The oldest people in the village, who whispered that she had already been in communication with angels" (125) in Chapter LXXII, foretell her ascent to Heaven.

The Equivalent Illustrations from the Household Edition Volumes (1872 and 1876)

Left: Harry Furniss's final illustration focuses on Grandfather Trent's grief instead of Nell's beautiful corpse: The Death of Little Nell (1910). Right: Thomas Worth's emotional scene of parting between the grandfather and the dying Nell: She turned to the old man with a lovely smile upon her face (Chapter LXXII).

Left: Cattermole's valedictory tailpiece shows the saintly Nell born aloft by angels, with the cemetery below, in The Spirit's Flight (Chapter LXXIII). Right: Charles Green provides a re-interpretation the scene that focuses on the grief of the living, Kit Nubbles and Grandfather Trent: "Master!" he cried, stooping on one knee and catching at his hand. "Dear Master! Speak to me!" (1876).

Related Material Including Other Illustrated Editions of The Old Curiosity Shop

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Dickens (homepage)

- The Old Curiosity Shop Illustrated: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works."

- The Original Serial Illustrations for The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41)

- Felix O. C. Darley (4 photogravure plates, 1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (12 wood engravings, 1867)

- Thomas Worth (53 wood-engravings, 1872)

- Charles Green (39 wood-engravings, 1876)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by W. H. C. Groome in the Collins' Clear-Type Press Edition (nine lithographs, 1900)

- The Old Curiosity Shop (1910) by Harry Furniss in the British Charles Dickens Library Edition (31 lithographs plus engraved title)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (13 lithographs from watercolours)

- Harold Copping (2 chromolithographs selected)

Scanned image and editing by George P. Landow; caption and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ciugureanu, Adina. "Dantean Echoes in The Old Curiosity Shop." Dickens Quarterly, 52, 2 (June 2015), 116-28.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Chapter Five: George Cattermole." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980. 125-34.

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop in Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Phiz, George Cattermole, Samuel Williams, and Daniel Maclise. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury and Evans, 1849.

_______. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Thomas Worth. Nicholas Nickleby. Illustrated by C. S. Reinhart. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1872. I.

_______. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. XII.

_______. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. V.

Created 4 January 2006

Last modified 15 November 2020