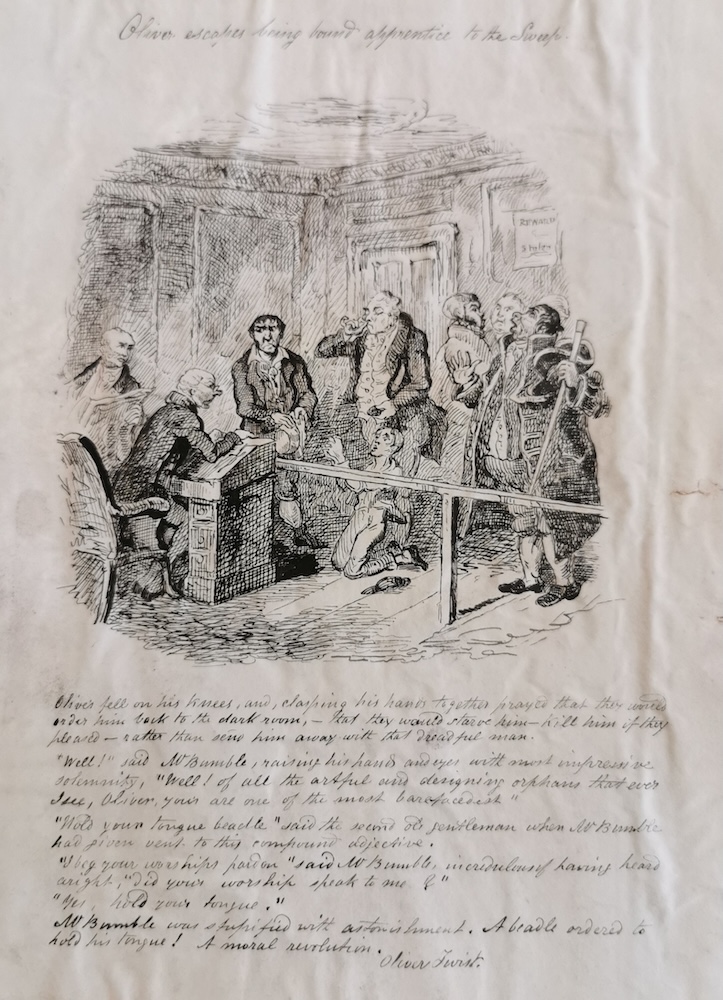

Oliver escapes being made apprentice to the Sweep [Link].

Oliver Twist's complicated publication history makes it hard to determine the exact background to seven illustrations that appear in an album/scrapbook of the early Victorian period, alongside hundreds of other assorted illustrations.

What we do know is that, towards the end of 1836, a promising young author, Charles Dickens, made a new career move. His first novel, The Pickwick Papers, was still coming out in shilling parts from the publishers Chapman and Hall. Now, under the pseudonymn of Boz, which he had used for his early journalistic sketches, he took up the editorship of a literary journal, Bentley’s Miscellany. Its first number appeared in the January of 1837. In the next issue, hoping to build on his success with his first effort of this kind, Dickens launched a new one, entitled Oliver Twist. George Cruikshank, who had previously illustrated those journalistic Sketches by Boz, and who was to a certain (disputed) extent involved in the genesis of this new project, would provide illustrations. Oliver's adventures duly appeared in serial form in the Miscellany, monthly from February 1837 to April 1839, enlivened by Cruikshank's artistry. The chapters ran in the first three bound volumes of the publication, before being issued in revised form as a triple-decker novel.

Cruikshank's earliest attempts at realising the characters were quick sketches. Here, for example, are his first ideas about Bill Sikes, Nancy, and the Artful Dodger (Kitton, Plate XI, facing p. 20):

Cruikshank then prepared detailed etchings for woodcuts.

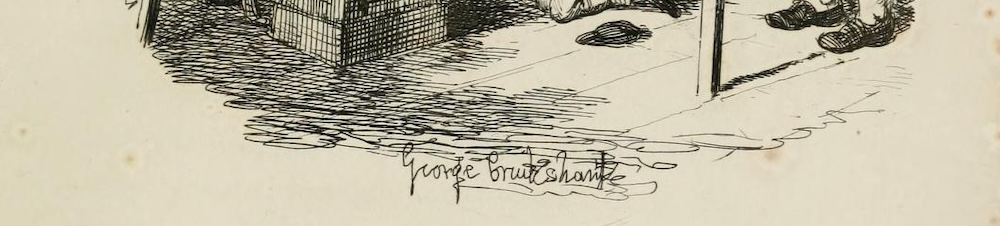

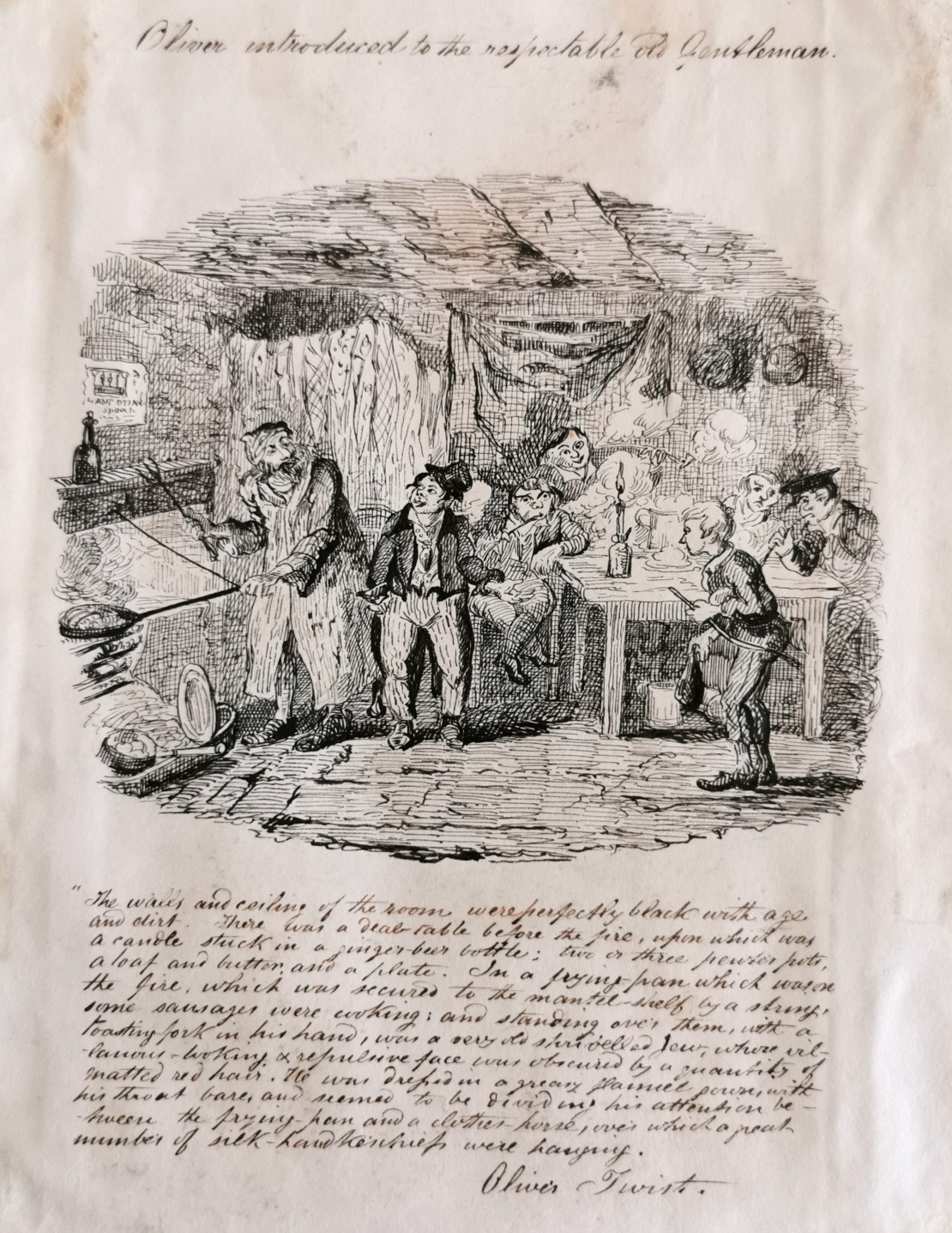

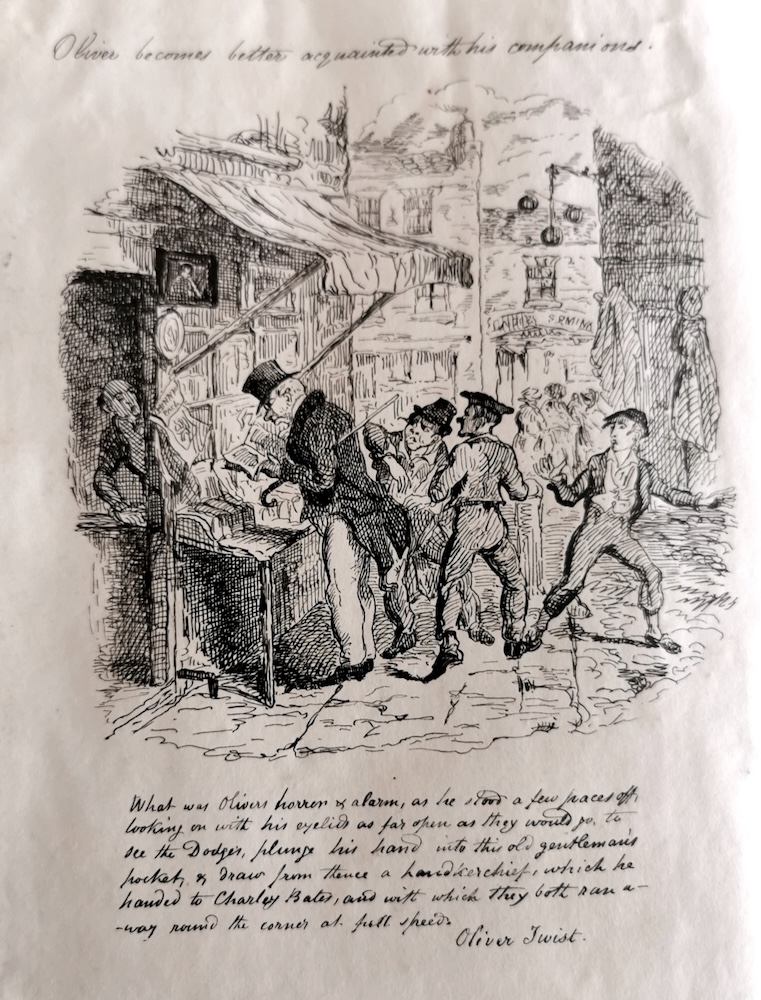

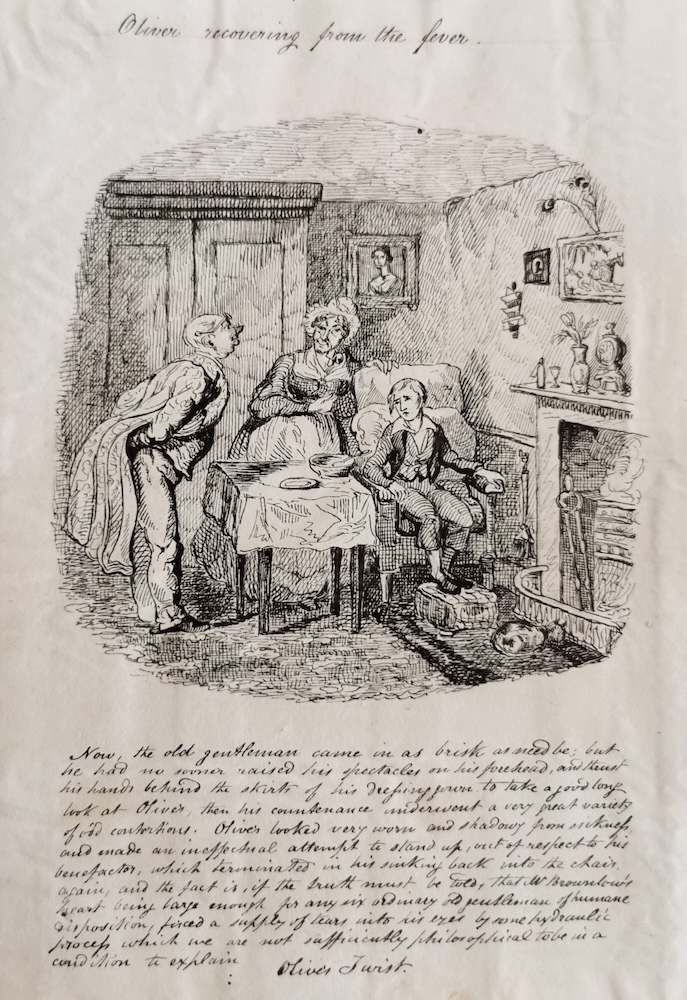

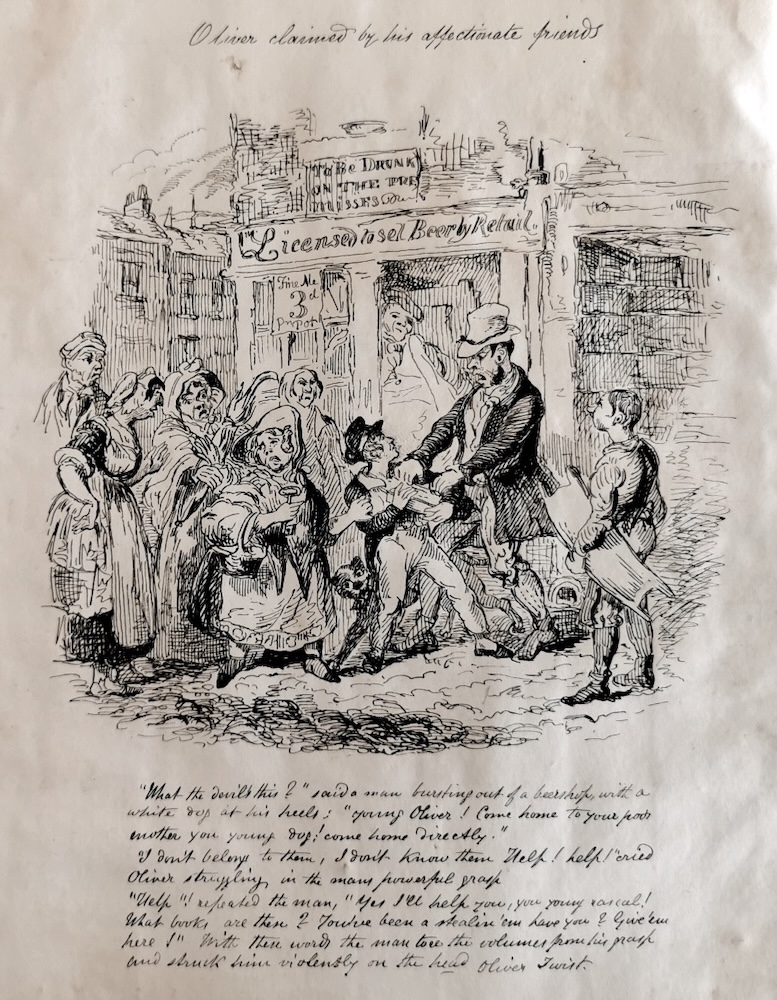

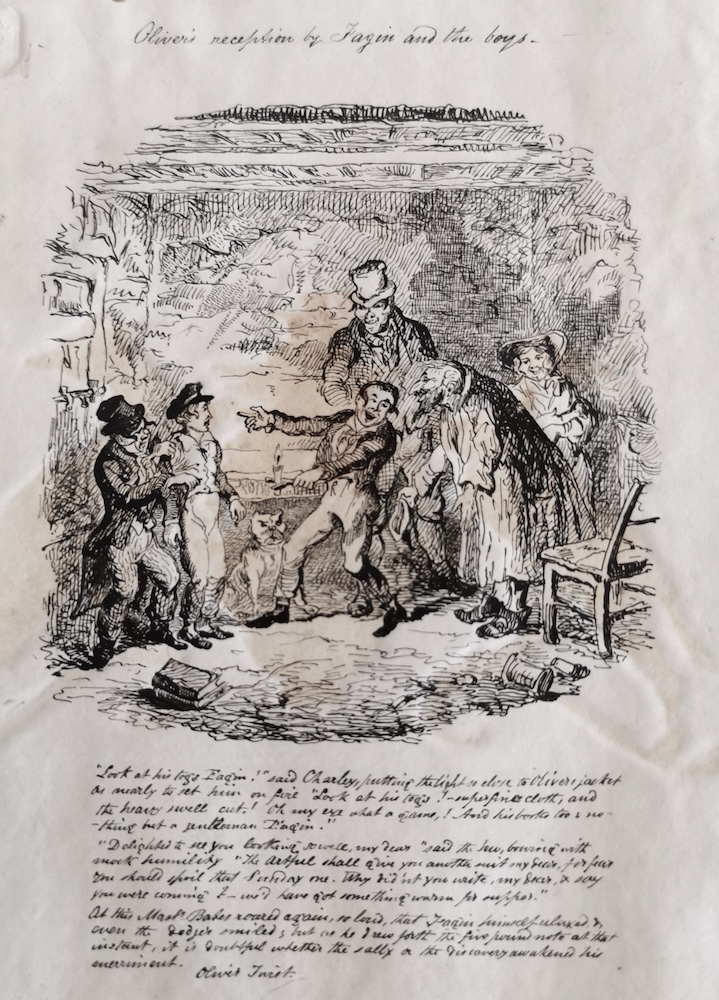

The set of seven illustrations found in the album tallies with those in the Miscellany's early instalments, and the first edition of the book. The scenes are not pasted into the album on their own, but within page sheets, on which there is handwriting rather than printed matter. Nor do they carry Cruikshank's signature, which in the published works sometimes segues into the lowest lines of the drawing:

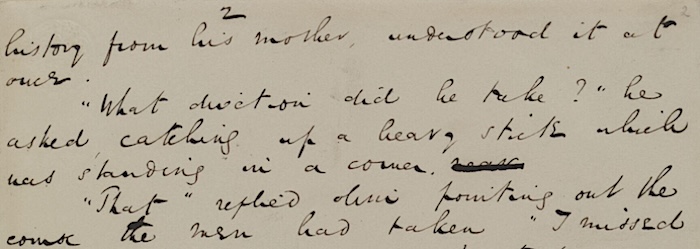

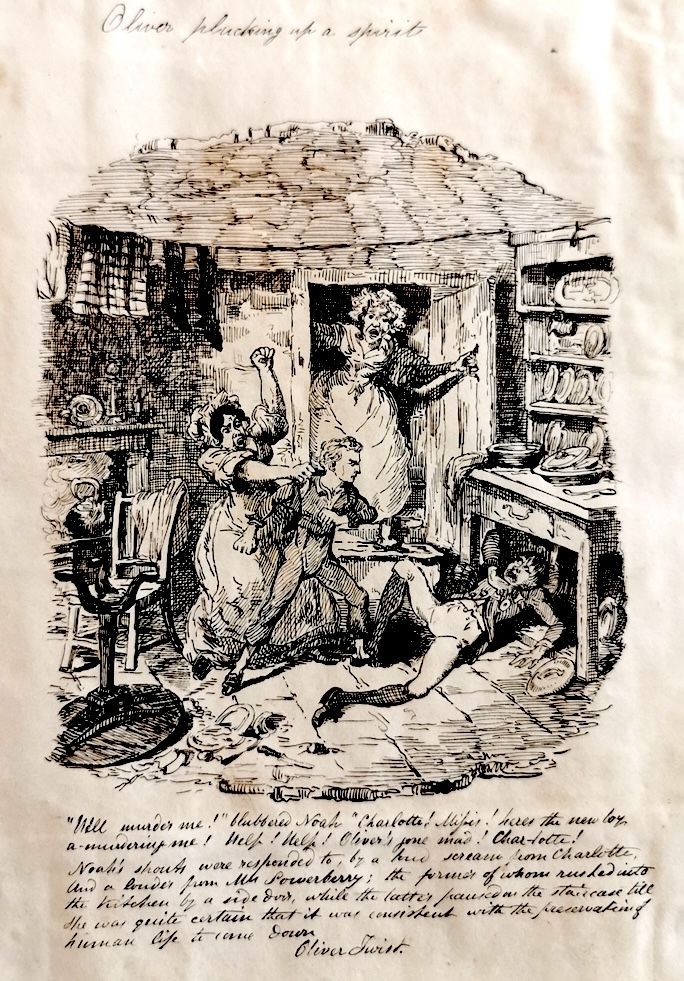

Instead, each of the unattributed illustrations shown in the album, measuring 23 x 19 cm., is accompanied by written text, added directly beneath the image. These inscriptions correspond correctly to the illustrated scenes and vary from 7 to thirteen lines long. The illustrations also have headings in the same handwriting, not always precisely the same as the printed captions. For example, "Oliver plucks up a spirit" becomes "Oliver plucking up a spirit." It is tempting to speculate that these written additions might have come from Dickens's own pen: a brief excerpt from the manuscript of Oliver Twist, sourced from the Victoria and Albert Museum's site (and downloaded, as permitted, for educational use), shows an untidy and impatient hand when the novel was in full flow, but in its clearer passages Dickens's handwriting does bear some similarities to the neat text on the album's pages:

What was the purpose, then, of these copies? The album series certainly indicates that a contemporary was following along with interest, carefully identifying the pictorial accompaniment to the letterpress. This reinforces the idea that the illustrations were a great attraction. The critic Janet Cohen has rounded up some of the praise heaped on them at the time. Interestingly, she also quotes one journalist who went so far as to suggest that it was Cruikshank's work that inspired Dickens's, rather than the other way around — that "the letterpress was written 'to match, as per order' the artist's wishes" (qtd. p. 32). Might it even that these carefully preserved copies reflect the author's own active involvement in relating the text and its visual interpretation during the Bentley period — perhaps while the triple-decker book was in preparation? This rather depends on whether the album could, in fact, have originated in or been connected with the Bentley offices, itself a matter of speculation.

Such speculation aside, note that the illustrations, as they appeared in book form, are all fully discussed elsewhere on this website. Click on the images to enlarge them, and click on the links for the discussions.

Left: Oliver plucking up a Spirit [Link]. Right: Oliver introduced to a respectable old gentleman [Link].

Left: Oliver becomes better acquainted with his companions [Link]. Right: Oliver recovering from the fever [Link].

Left: Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends [Link]. Right: Oliver's reception by Fagin and the Boys [Link].

Related Material

- Album/Scrapbook (c.1838-1855): A Rich Source of Early Victorian Illustrations

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

- Oliver Twist as a Triple-Decker

- Oliver untainted by evil

- Like Martin Chuzzlewit, the novel agitates for social reform

Image scans by Randall Wallace and text by Jacqueline Banerjee. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Memoir of Middle Age. London: Vintage, 2012.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980.

Dickens, Charles ("Boz"). The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, Vol. I. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: R. Bentley, 1838. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Web. 7 February 2026.

Kitton, Frederic George. >Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Coyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fields. With twenty-two portraits and facsimiles of seventy original drawings now reproduced for the first time. London: G. Redway, 1899. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Getty Research Institute. Web. 7 February 2026.

The Original Manuscript of Oliver Twist. V&A. Web. 9 February 2026.

Created 9 February 2026

Last modified 21 February 2026