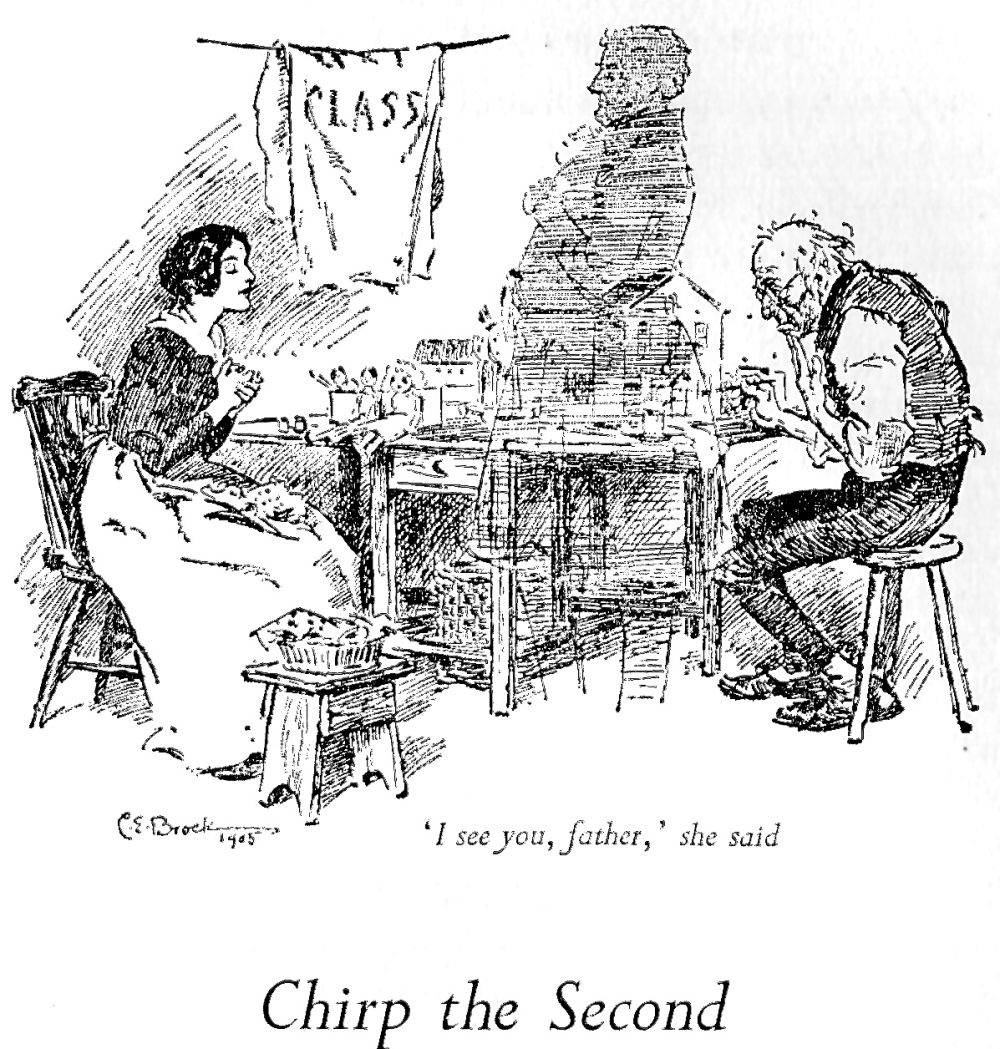

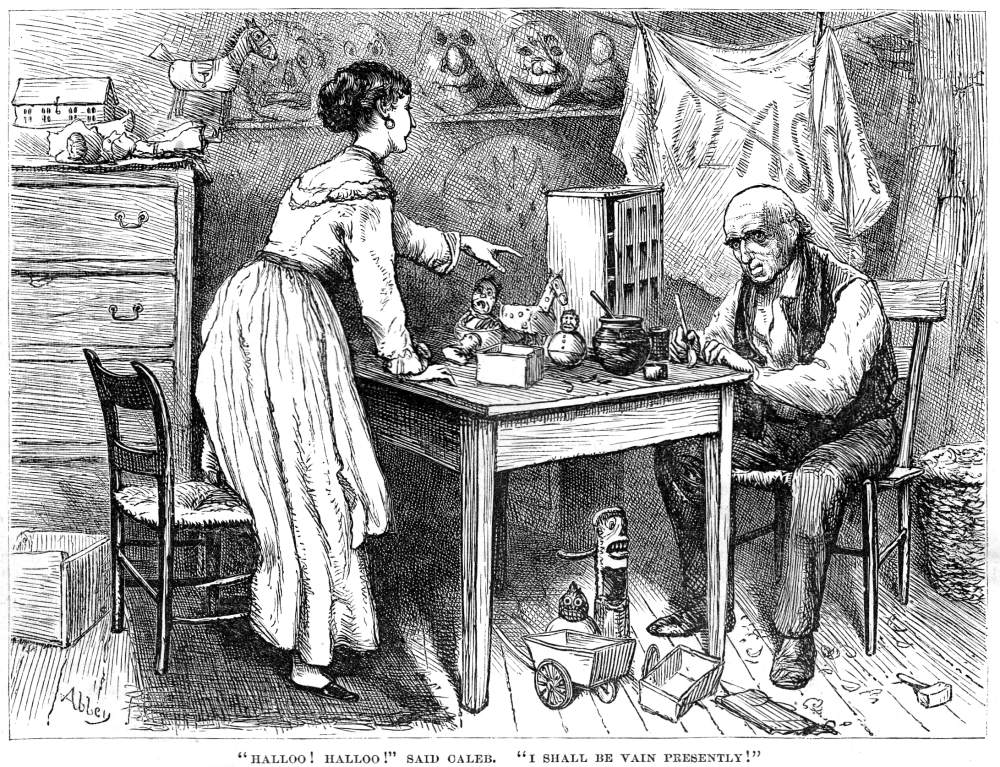

"I see you, father," she said (1905), a half-page illustration for "Chirp the Second," 7.7 cm by 10 cm, vignetted (137).

Context of the Illustration

"So you were out in the rain last night, father, in your beautiful new great-coat," said Caleb's daughter.

"In my beautiful new great-coat," answered Caleb, glancing towards a clothes-line in the room, on which the sack-cloth garment previously described, was carefully hung up to dry.

"How glad I am you bought it, father!"

"And of such a tailor, too," said Caleb. "Quite a fashionable tailor. It's too good for me."

The Blind Girl rested from her work, and laughed with delight.

"Too good, father! What can be too good for you?"

"I'm half-ashamed to wear it though," said Caleb, watching the effect of what he said, upon her brightening face; 'upon my word! When I hear the boys and people say behind me, 'Hal-loa! Here's a swell!' I don't know which way to look. And when the beggar wouldn't go away last night; and when I said I was a very common man, said 'No, your Honour! Bless your Honour, don't say that!' I was quite ashamed. I really felt as if I hadn't a right to wear it."

Happy Blind Girl! How merry she was, in her exultation!

"I see you, father," she said, clasping her hands, "as plainly, as if I had the eyes I never want when you are with me. A blue coat — "

Bright blue," said Caleb. [Chapter Two, "Chirp the Second," 142]

Commentary

Here Brock re-drafts John Leech's original toyshop scene (see below) in which Caleb Plummer tries to persuade his blind daughter, Bertha, that they are well off and that Tackleton, their employer, is kind and generous. In the program of illustration in the original, 1845 edition of The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Hearth and Home, Charles Edmund Brock would, in fact, have found two useful models, and the British Household Edition would have offered him a further example, Caleb, Bertha, and Tackleton (see below). The previous illustration closest in composition to Brock's (but which he may never have seen) is "Halloo! Halloo!" said Caleb. "I shall be vain presently!" (see below) by E. A. Abbey in the American Household Edition. Although the British Household Edition illustrator, Fred Barnard, had provided him with an image of Tackleton's visiting the workroom, Brock's innovation was to impose a transparent or ghostly profile of the employer to suggest the blind girl's figmentary understanding of the cynical capitalist. Her belief that he cares about her and her father is simply ill-conceived. Although the Brock drawing seems rushed and incomplete, its psychological dimension reveals more about the blind girl than the original and Household Edition versions of the same scene.

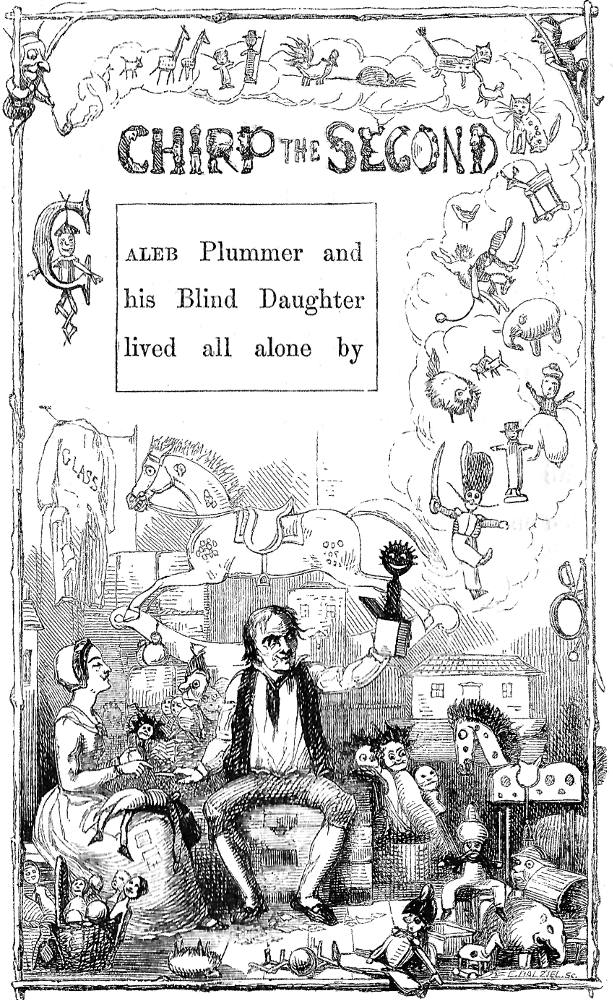

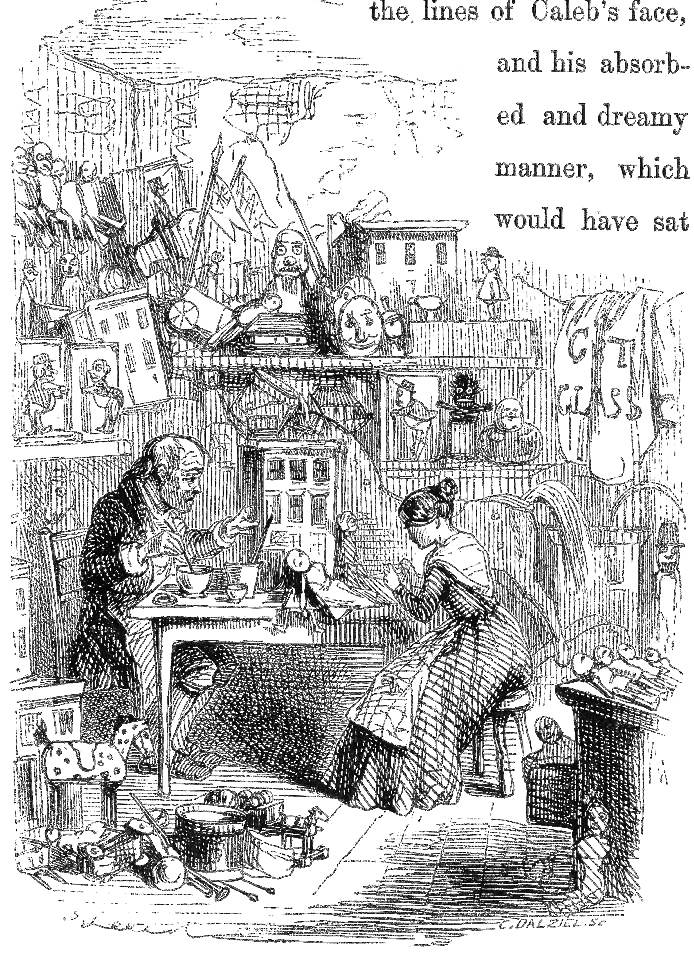

Relevant Illustrations from various editions, 1845-1878

Three illustrations of Caleb and Bertha Plummer in their parlour, which doubles as their workroom: Left: Richard Doyle's "Chirp the Second". Centre: John Leech's "Caleb at Work". Right: Fred Barnard's Caleb, Bertha, and Tackleton (1878).

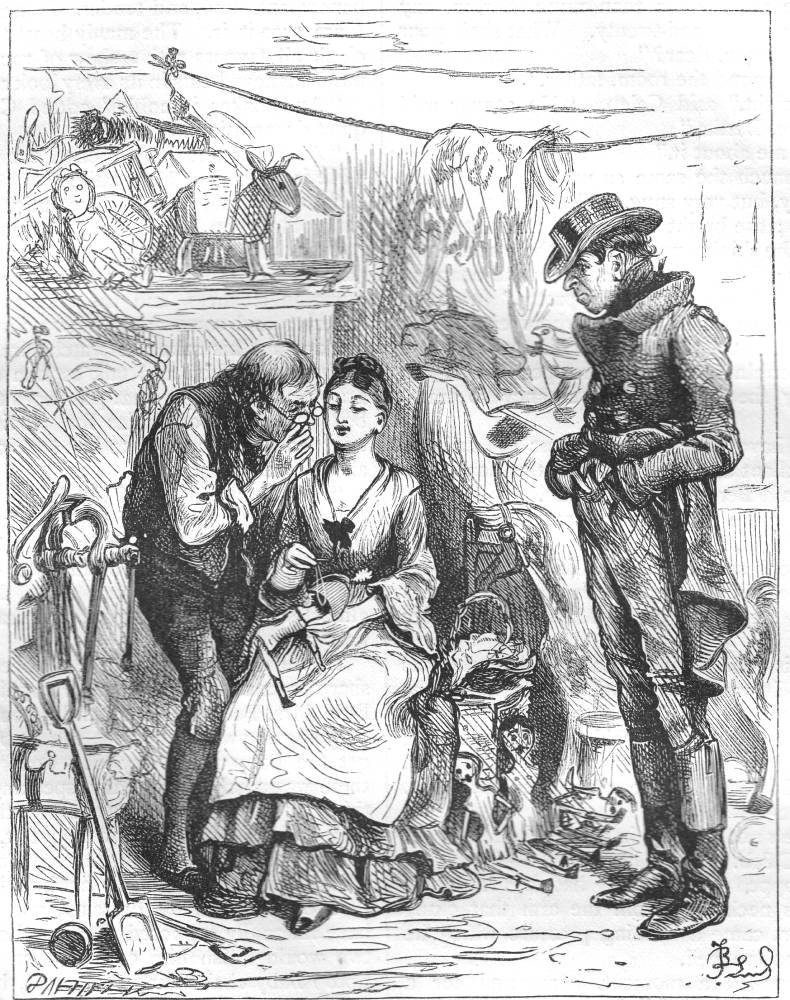

Above: E. A. Abbey's 1876 composite wood-engraving of the activity of the toy-makers in their hovel, "Halloo! Halloo!" said Caleb. "I shall be vain presently!"

Caleb's Threadbare Great-Coat

The various illustrators have included Caleb's wonderful great-coat — just a threadbare garment hanging on a clothesline, drying; the word "glass" indicates that it has been fashioned out of a sackcloth once used to pack fragile objects (upper left in Doyle, upper right in Leech; right of centre in Barnard; and upper left in Brock). In Leech's, Barnard's, and Abbey's versions of the same scene, the so-called "great-coat" hangs drying on a clothes-line strung across the cluttered workroom, as Dickens's text specifies, whereas Brock shows but a piece of the clothesline. While Caleb is painting a dolls-house, Bertha is busy as "a Doll's dressmaker" (141), like Jenny Wren in Our Mutual Friend. In Abbey's and Brock's compositions, a respectably clad and fashionably coiffed Bertha points across the worktable at the dolls' "desirable family mansion" (87, Household Edition) — barely discernible as such in Brock. The comic part of the accompanying text is that he has obviously described himself to his daughter as youthful and "handsome," whereas the readers, studying the illustrations, apprehend the irony immediately through Caleb's extreme homeliness — Brock's Caleb is especially decrepit. Using the convention of closed eyelids to suggest Bertha's blindness, Brock uses the illustration of father and daughter at work on a dolls-house as a headnote vignette, establishing a proleptic reading that only the next five pages of text can clarify; in particular, the enigmatic figure of their employer, apparently studying Bertha, will be explained in the forthcoming text.

Other Illustrations for The Cricket on the Hearth (1845-1915)

- John Leech et al.: original 1845 series of fourteen engravings for Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867 illustrations for the Diamond Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- E. A. Abbey's 1876 illustrations for The American Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Fred Barnard's 1878 illustrations for The Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A. A. Dixon's 1906 Collins Pocket Edition for Dickens's Christmas Books

- Luigi Rossi's 1912 A & F Pears Centenary Edition of Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth

- Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_______. Christmas Books, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_______. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_______. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_______. Christmas Books, illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_______. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth, illustrated by C. E. [Charles Edmund] Brock. London: J. M. Dent, 1905; New York: Dutton, rpt., 1963.

_______. Christmas Stories, illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

_______. The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edwin Landseer. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1845.

Created 20 October 2015

Last modified 8 July 2020