eorgina Bowers (1835–1912) is a little-known contributor to the discourse of Victorian illustration. The only modern consideration of her art and life is by Mark Bryant, who establishes the outlines of her career as a Punch cartoonist and as the author of a number of plate-books about fox-hunting. This was her main interest, as an accomplished horsewoman, and the principal subject of her amusing social satire.

Despite her relative obscurity in the twenty-first century, Bowers was a popular figure in her own time. Her books were widely publicised in publishers’ advertisements and sold well; the Art Journal praised her ‘clever sketches’ and ‘broad humour’ (‘Society’ 88) and M. H. Spielmann described her as ‘by far the most important lady artist who ever worked for Punch (529). Her accomplishments were always noted in these terms, and her position as a woman working in a male-dominated profession endowed her with the status of novelty: like other female practitioners such as Mary Ellen Edwards, Helen Allingham and Kate Greenaway, she stood out in what was essentially a patriarchal artistic culture.

She was especially noted for being a female humourist. Writing in her study of 1876, Ellen Clayton noted how women’s participation in comic art was unusual because it involved a certain coarseness that was (supposedly) a male domain:

… it may be urged that Humour is a quality scarcely coveted by the ladies. They like to be admired for wit, archness, piquancy, even sarcasm, or any similar attribute that may be slightly tinged with a soupçon of the comic – but Humour, as a rule, they willingly relegate to those who care to claim it. Wit is fine and elegant: wit shines and scintillates in drawing-rooms and boudoirs, but Humour may run the risk of stepping over the boundary lines of vulgarity. Thus, it may be, arises the otherwise singular fact that so few women have come forward as humorists, though many have been famous for wit or sarcasm. [319 –320]

Bowers’s comedy was viewed, in other words, as a sort of gender-testing activity, placing her next to other female satirists such as Lady Dufferin and Florence Claxton as a woman who managed to create a professional and artistic space for herself. The character of her work is outlined here, along with some biographical details.

Background and Career

Georgina Harriet Bowers was from a staunchly middle-class and respectable background. Her father was the rector of St Paul’s, London, later to become the Dean of Manchester, and had connections with the Duke of Bedford. The family were comfortably well-off and Georgina enjoyed the benefits of privilege. Her mother died when she an infant, and she was educated in a private school in Ashbourne, Derbyshire (Bryant 22), later living with her father in Salford. In 1864 she moved to Hertfordshire, where she could enjoy riding (23).

Bowers’s training as an artist is obscure. Bryant notes that she studied at the Manchester School of Art (23) which had been set up as the School of Design in 1838; however, female students were not admitted until 1880, so she must have undergone some other form of training, or, likelier, was self-taught. Working in a period when ‘amateur sketching’ was a ‘respectable practice … for a lady’ (Cherry 83), she probably initiated her artistic career as a hobbyist, and there is no doubt that her formal skills were limited and perhaps amateurish. As the Art Journal remarked of her drawings, her artistic ‘intention is better than [her] execution’ (89). Like M. E. Edwards, who was largely self-taught (Cooke 95), Bowers had to overcome the professional limitations imposed on female artists, and was adept at exploiting her strengths to best effect.

Her talent as a draughtswoman was certainly recognized, as was her skill as someone who could ‘draw on wood’ and prepare her blocks for engraving. Aged around 30, she submitted her cartoons to Punch, and was immediately encouraged to become a regular contributor by the editor, Mark Lemon, the magazine’s engraver, Joseph Swain, and, most tellingly, by the lead artist, John Leech (Bryant 23). As Spielmann explains, her ‘long career began in 1866’; ‘working with undiminished energy’ for the next years, she ‘executed hundreds of initials and vignettes as well as “socials,” devoting herself in chief part to hunting and flirting subjects’ (529). Bryant notes that she did full and part-page designs in addition to the small pieces, contributing in all around 100 cartoons; she discontinued her contributions in 1874, feeling that Lemon’s successor, Tom Taylor, was uninterested in sporting themes, although her final design appeared in Punch in 1878 (Bryant 23).

Bowers also worked as a contributor to other periodicals, notably Once a Week and London Society, as an illustrator for children’s books such as The Little Child’s Fable Book (1868) and Barbara Hutton’s Castles and their Heroes (1868), and as a visual interpreter of an edition of Mrs Craik’s Olive (1875) and other minor fictions. Her strongest work, however, was in the form of her series of comic-equestrian picture books in which she did the images (reproduced in chromolithography from her watercolours), and captions, as well as designing the covers; these included A Month in the Midlands (1868) and Hunting in Hard Times (1889). Always a keen hunter, who was apparently one of the first women to ride rather than follow the hunt in a carriage (Bryant 27), her fascination with horses was supported by her marriage (in 1871) to the vet Henry Edwards. Edwards specialized in the equestrian, and Bowers was able to apply her knowledge of the animals to her visual, comedic representations of the culture of hunting.

Bowers later worked in fine art as opposed to illustration, although there was no clear distinction between the two sets of images. She was a member of the Society of Female Artists and 1910 exhibited 40 watercolours at the Modern Gallery, London (Bryant 27). Throughout her life Bowers lived in Hertfordshire, firstly in St Albans and later, following the death of her husband, in Common Wood, near Langley. She passed away in 1912.

Equestrian Picture-Books

Horses were a prime constituent of nineteenth century culture. Despite the rise of a steam-based technology, for most of Victoria’s reign horses were still the prime means of motive power: agriculture largely depended on the working plough-horse, the moving of goods still relied to a large degree on workhorses, and horses, notwithstanding the impact of the train, remained a central mode of transport. Used to shift a plough, to pull a carriage or cart, or simply to relay a single rider, horses were ubiquitous; they were also used by the upper classes as symbols of wealth and status, the emblems of class as much as the living motors of utility.

Equestrian art flourished in this context as a genre that extended from painting to cartoons and illustrations. Bowers worked within this cultural frame; in particular, her work reflected the contemporary fascination with fox hunting, which, according to Jeremy Maas, was not only the preserve of the privileged and the old county elites, but was characterized by a ‘growing classlessness’ (70). Indeed, Bowers was one of several artists who celebrated the democratization of the hunt as a sort of comedic space where riders of all social backgrounds could be allowed to make fools of themselves as they struggled with various forms of obstacles and difficulties.

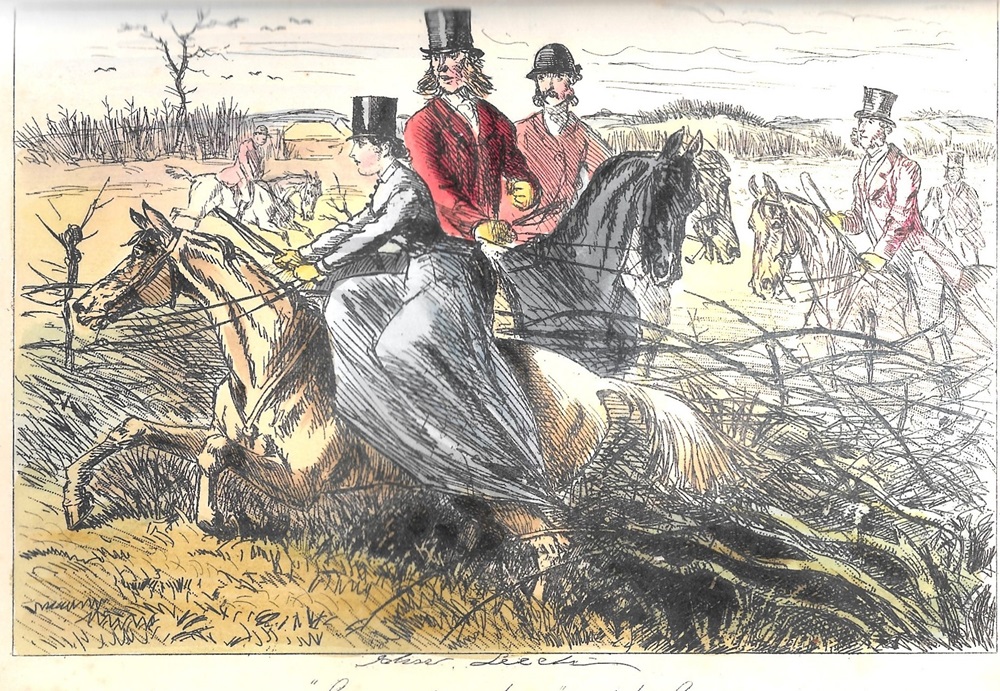

In formulating this approach she was heavily influenced by John Leech, one of her champions at Punch. Leech provided Bowers were a visual template in the form of his equestrian cartoons for the Jorrocks books by Robert Surtees. Leech focused on the absurdities of the hunt-obsessed Jorrocks, and Bowers echoes the many moments of incompetence; as the Art Journal noted, her cartoons were very much in the manner of Leech’s situational ‘broad humour’ and comic ‘burlesques’ (89). Following Leech, Bowers offer a series of comedic situations as her comic figures have a hard time trying to enjoy themselves.

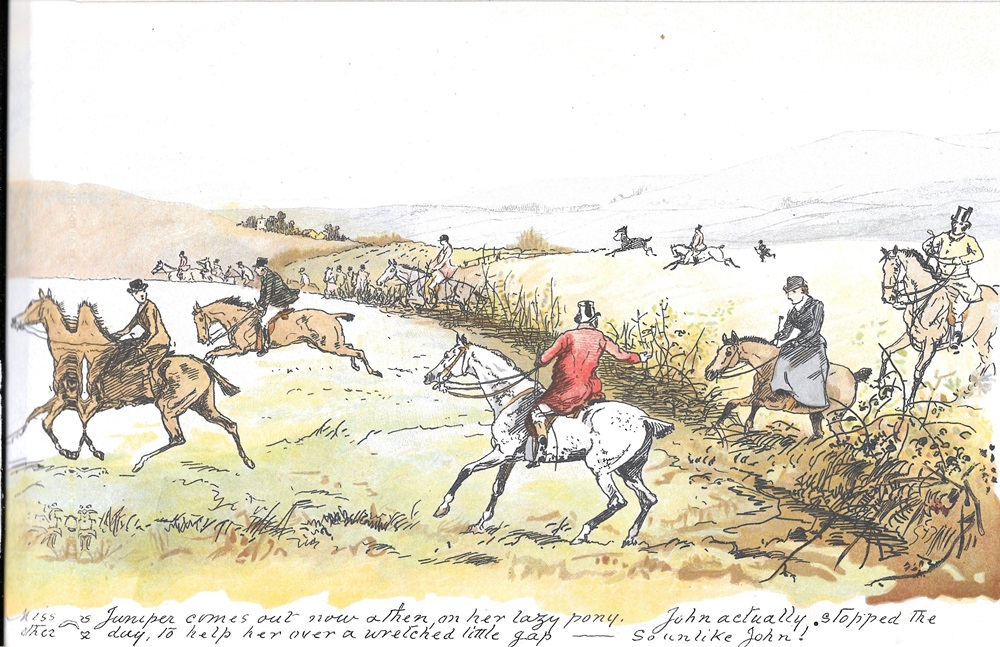

Leech’s influence on Bowers. Left: Leech’s ‘Let me try them,’ said Lucy; and Right, by Bowers: Miss Juniper comes out now and then on her lazy pony.

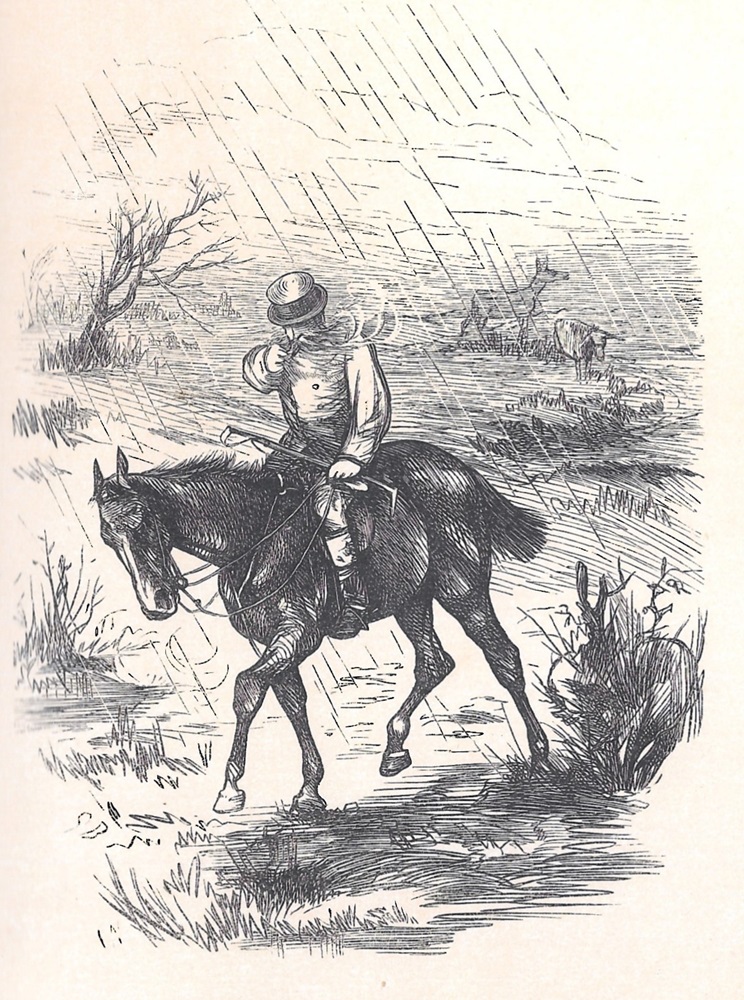

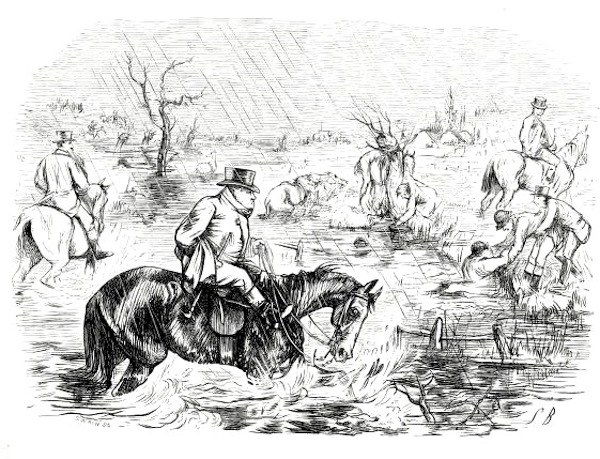

Two of Bowers’s characteristic images of bad weather and obstacles Left: A wet ride home; and Right: Farmer Gripper begins to wish he could swim home.

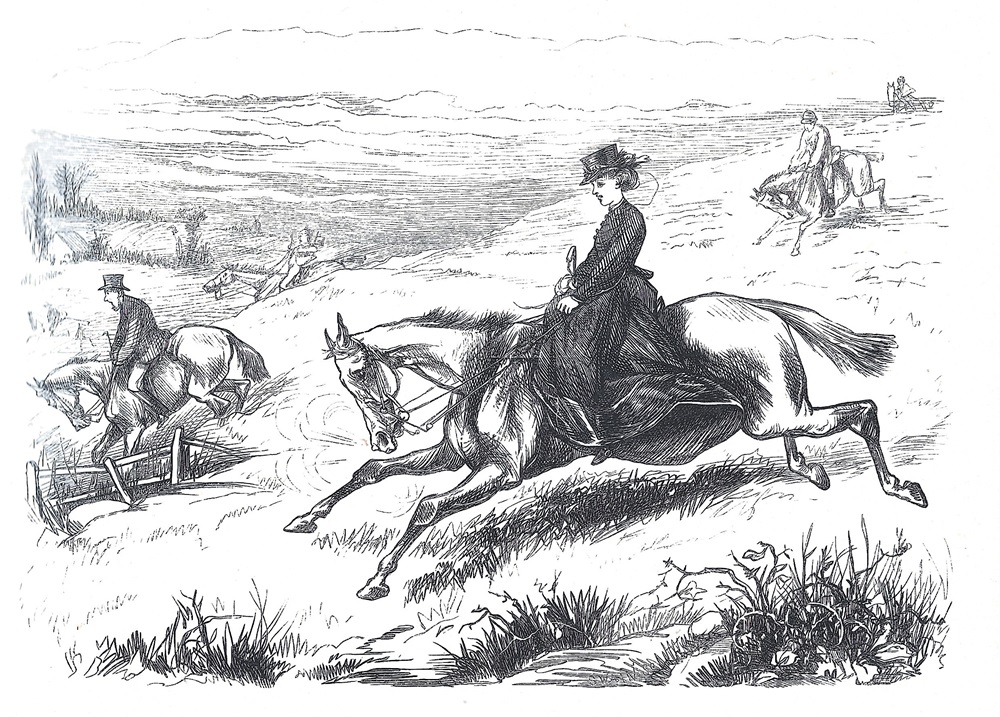

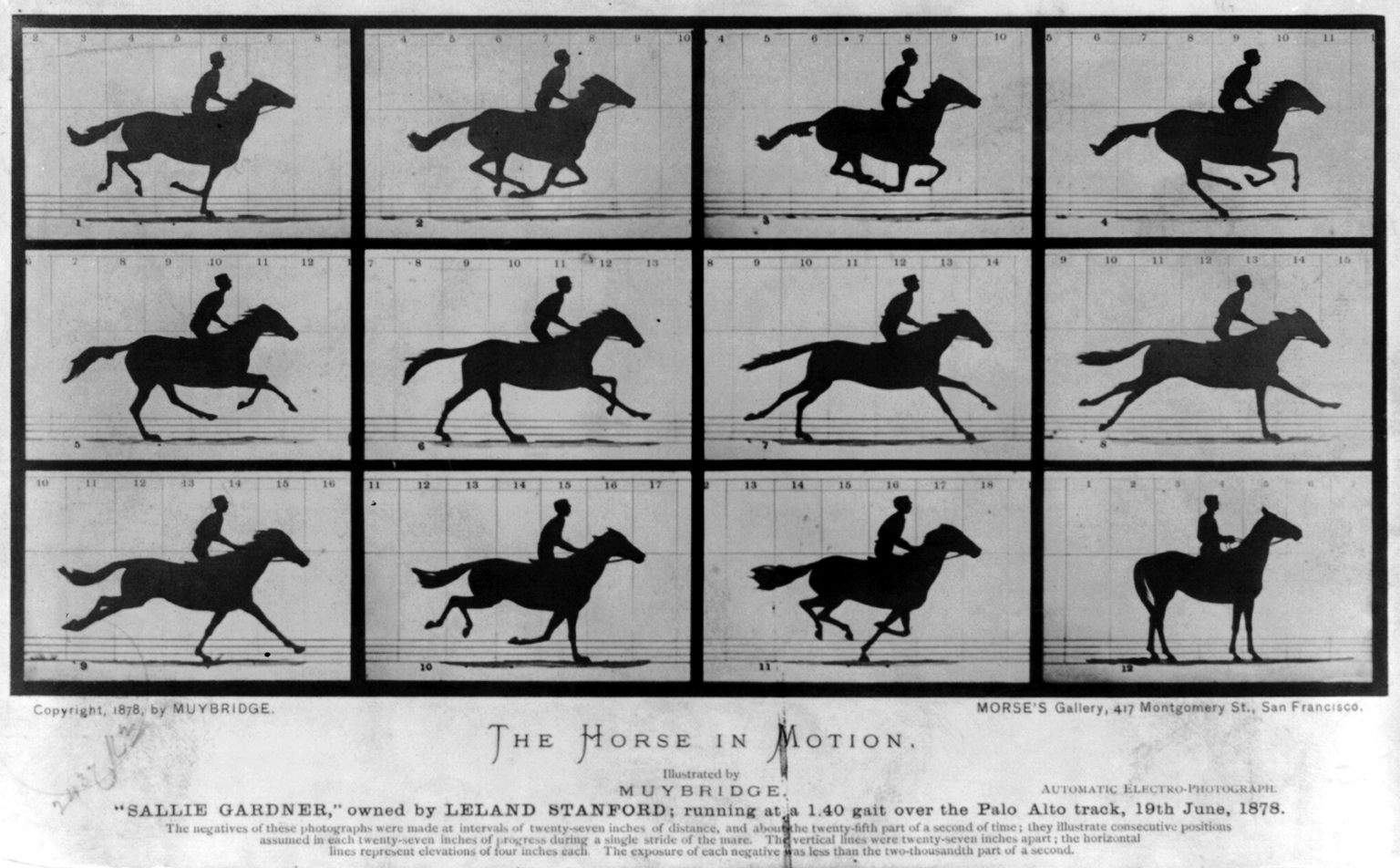

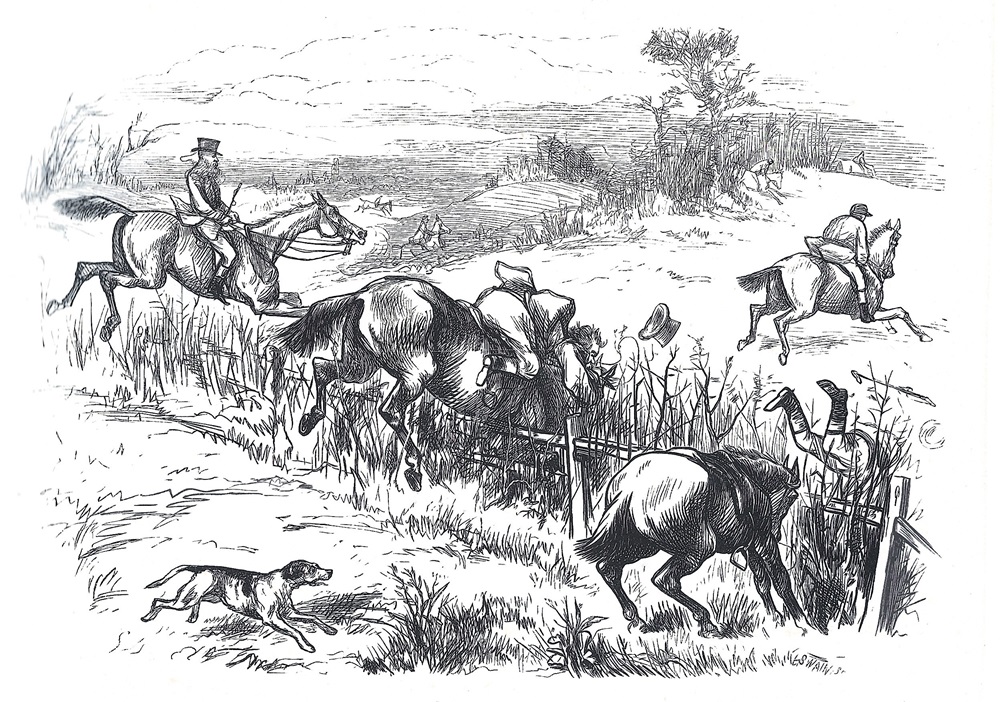

The weather is a constant problem as riders cope with pouring rain and muddy surfaces; even when all seems well, there is always a hurdle or a ditch that seems about to unhorse the hunter. One cartoon, A fast thing across country in Month in the Midlands (1868), shows a lady rider, presumably based on Bowers’s own experience, as her mount gallops confidently forward; but another rider to the left is stumbling, with the implication that she too will suffer a fall. In every case, Bowers stresses the vitality of the chase: produced before Edweard Muybridge’s photographic experiments in the late 1870s, which conclusively proved the movements in a horse’s gallop, her images show horses bounding forward with both front and rear legs extended as if they were rocking-horses.

One of the artist’s rocking-horses at full tilt. Left: A fast thing across country; and Right: one of the frames by Muybridge (1878) showing animal locomotion and the real sequence of movements.

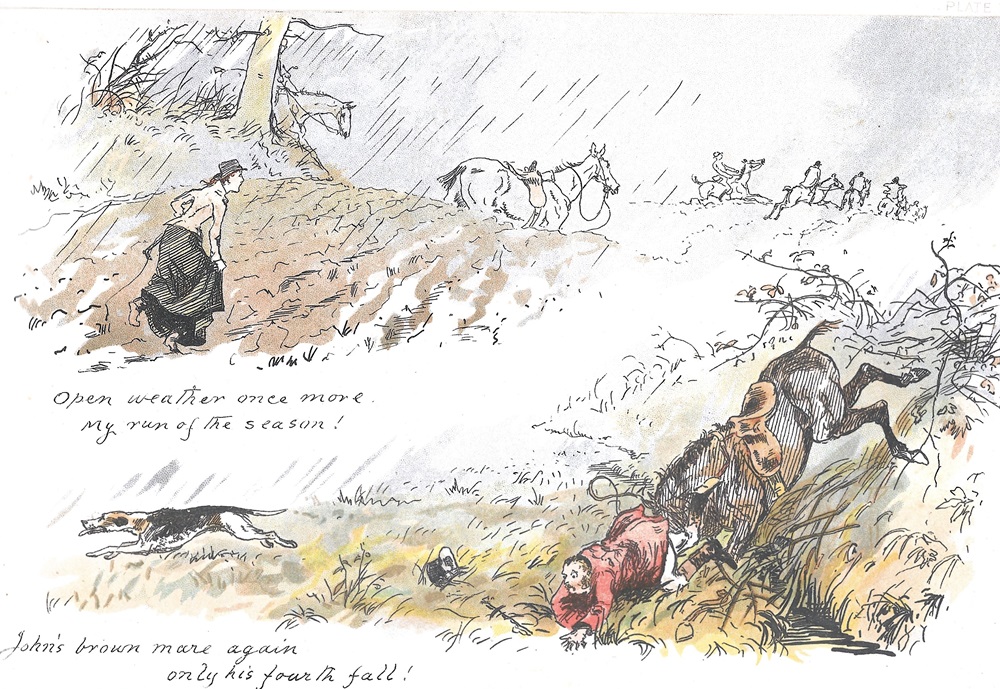

Of course, hunting offers relatively few opportunities for comedy, but Bowers emphasises the farcical and the haplessly unexpected. These images reflect an intimate knowledge of the sport and are based on close observation which informs her manipulation of Leech’s comedic conventions; as Clayton reports, she always rode with ‘a sketch-book which fits into a saddle-pocket’ (323), using it to draw backgrounds and, no doubt, the hunt’s accidents and incidents. The effect is always ludicrous, mocking the ritualism of the chase by reducing it to the level of pantomime travesty; nevertheless, the satire is essentially benign and self-indulgent, a view of hunting from the perspective of an enthusiastic insider. Noticeably, she completely avoids the cruelty of such events; though foxes are represented they are never shown being killed and pulled to pieces, nor does she show any of her characters being blooded. Good taste, as in the art of Leech, is always preserved, even if the evasiveness of Bowers’s art might seem difficult to accept by some observers of our own, ‘modern’ age.

Left to right: two illustrations showing the sheer, farcical difficulty of riding across open ground made difficult by the enclosure of farm land and unrelenting rain.

Bowers is not confined to the seemingly chaotic progress of the hunt, however. She also satirizes the bourgeois culture enclosing it, focusing especially on the characters of those who participate in the sport. These larger narratives are brought out in Hunting in Hard Times (1889), a chromolithographic montage of her watercolours which reproduces the artist’s handwritten captions and descriptions.

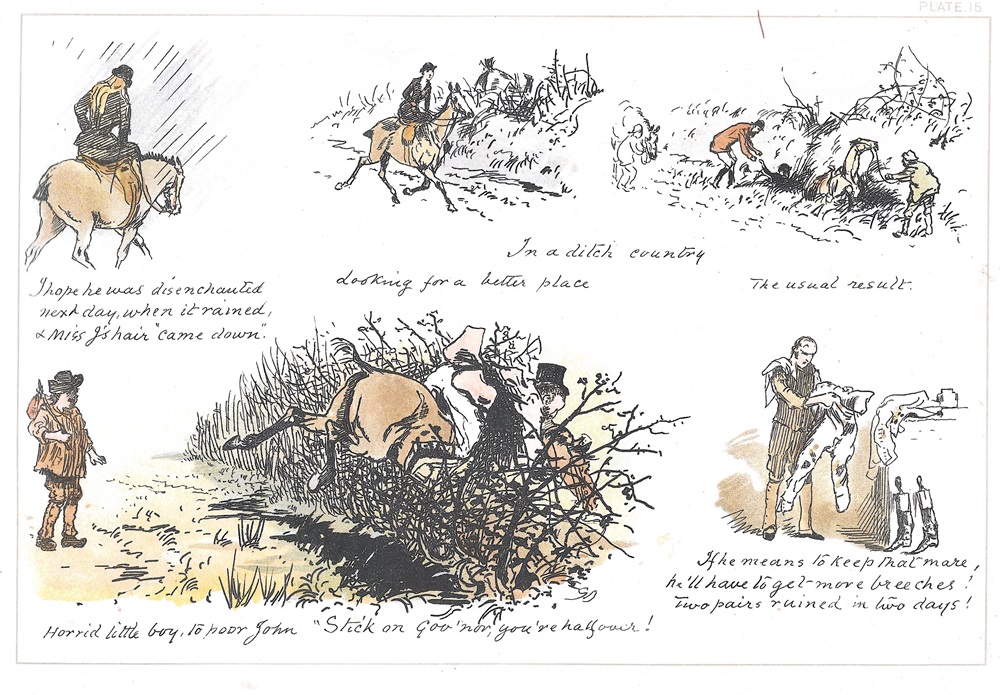

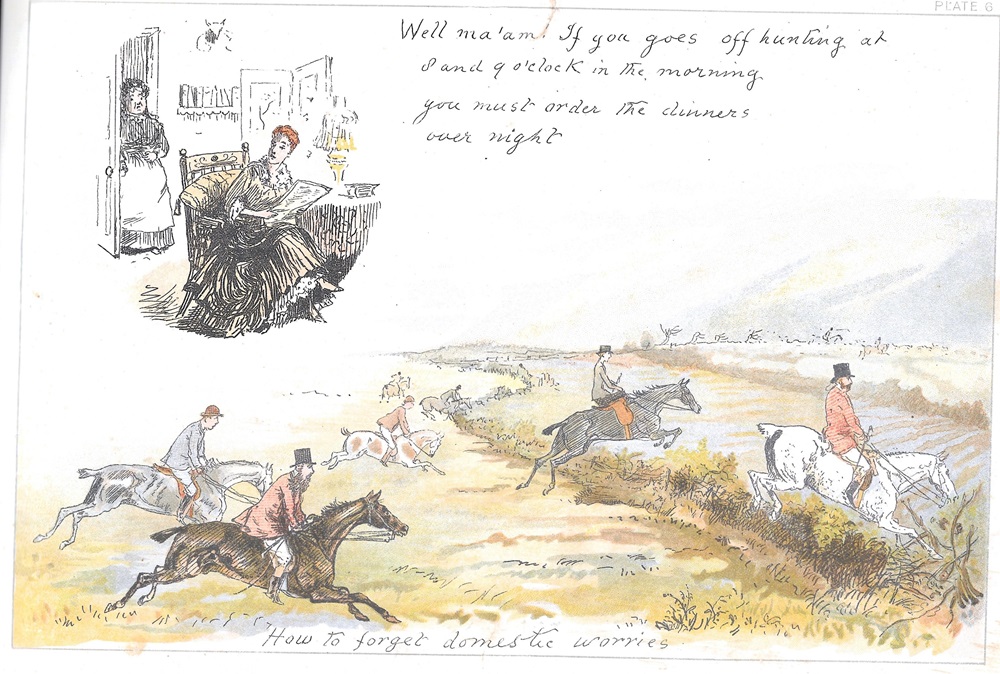

In Hunting, Bowers mocks the interconnectedness of the chase and its wider implications by juxtaposing a scene in the field with social or domestic events. In one montage, she combines a vignetter of a horse being grounded in a ditch and another with John, one of the riders, trying to ride through a hedge; to the right of this is the consequence of the attempted jump, as the character contemplates his wrecked breeches with the caption, ‘Two pairs ruined in two days!’ A life of hunting is therein framed by the prosaic domesticity of the everyday, a comic resonance which is further amplified in a plate depicting the hunt and an image of the artist’s cook declaring, with the grammatical incorrectness traditionally associated with the servant class, that ‘if you goes off’ at 8 am ‘you must order the dinners overnight.’ The comment is countered by the elegant jumping in the scene below and the caption, ‘How to forget domestic worries’; nothing is allowed to get in the way of the pursuit of pleasure for those who do not have to work.

Two scenes showing the interconnectedness of everyday life and the travails of hunting. Left: John and his wrecked breeches; and Right: Cook asserts the need to book dinner if her mistress must ride so early in the morning.

This combination of the everyday and the exhilaration of the sports runs throughout Bowers’s pictorial satire, offering a portrait of the middle-classes at play and in their domestic milieu. In this respect she works in another well-established tradition, this time partaking of the conventions of the picture-book album, popular through the nineteenth century, which ridiculed, bourgeois mores. Richard Doyle’s Manners and Customs of the Englyshe (1849), Bird’s Eye Views of Society (1864), H. K. Browne’s (Phiz’s) Sketches of the Seaside and Country (1886), and Dufferin’s travelogue, Lispings from Low Latitudes (1865) contribute to this convention, and the albums by Bowers take their place next to them.

Taken as a whole, Bowers was an underrated humourist who effectively works within and extends the genial idiom of Leech’s comedy. Her touch is light, her humour droll in the refined manner of the time and her entertainment value, as a comic artist and writer, considerable; unlike some purveyors of Victorian comedy, Bowers is still amusing, and it is not surprising to find that her picture-books are treasured and command high prices in the antiquarian book trade. Interesting, too, is the books’ general condition; usually well-thumbed, they have clearly been favourites among their readers.

Bibliography

Primary

Bowers, Georgina. Hunting in Hard Times. London: Chapman & Hall, 1889.

Bowers, Georgina. A Month in the Midlands. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1868.

Craik, Mrs [Dinah Mulock]. Olive . London: Macmillan, 1875.

Hutton, Barbara. Castles and Their Heroes. London: Griffith & Farran, 1868.

The Little Child’s Fable Book. London: Griffith & Farran, 1868.

London Society (1866 –74).

Once a Week (1866–71).

Punch (1866–1878).

Secondary

Bryant, Mark. ‘Pink Lady.’ Illustration 61 (Autumn 2019): 22–27.

Cherry, Deborah. Painting Women: Victorian Women Artists. London: Routledge, 1993.

Clayton, Ellen Creathorne. English Female Artists. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1876.

Cooke, Simon. ‘A Genuine Talent: Mary Ellen Edwards.’ Nineteenth-Century Women Illustrators and Cartoonists. Ed. Jo Devereux. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2023. 93–112.

Maas, Jeremy. Victorian Painters. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1969; new ed., 1978.

‘Society of Women Artists.’ The Art Journal 31 (1869): 89

Spielmann, Marion Harry. The History of Punch. London: Cassell, 1895.

Bibliography of Books and Magazines Illustrated by Bowers

Note: A comprehensive bibliography of works has not been established. The following list is a tentative catalogue; other imprints probably remain untraced.

Bowers, Georgina. Hollybush Hall, or, Open house in an Open Country. London: Bradbury, Evans, 1871.

Bowers, Georgina. Hunting in Hard Times. London: Chapman & Hall, 1889.

Bowers, Georgina. Hunting, Shooting and Fishing: A Sporting Miscellany. London: Sampson Low, 1877,

Bowers, Georgina. Idylls of the Rink. London: [no publisher given], 1877.

Bowers, Georgina. Leaves from a Hunting Journal. London: Chapman & Hall, 1880.

Bowers, Georgina. A Month in the Midlands. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1868.

Bowers, Georgina. Mr Crop’s Harriers. London: Day & Son, 1889.

Bowers, Georgina. Notes from a Hunting Box (Not) in the Shires . London: Bradbury & Agnew, 1873.

Bowers, Georgina. Rough Riding. London: Jarrold & Sons, 1895.

Craik, Mrs [Dinah Mulock]. Olive. London: Macmillan, 1875.

D'Avigdor, Elim Henry. Fair Diana. London: Bradbury, Agnew, 1884.

D'Avigdor, Elim Henry. A Loose Rein. London: Bradbury, Agnew, 1887.

’Dragon’ [pseudonym of unknown writer]. Moosoo’s Run of the Season. London: 1880 (listed in Bryant, 26; book untraced).

’Dragon’ [pseudonym of unknown writer]. Tales for Sportsmen . London: Simpkin Marshall1880.

The Graphic (1874).

Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (1874).

Hutton, Barbara. Castles and Their Heroes. London: Griffith & Farran, 1868.

Roberts, Randal Howland. High-Flyer Hall: Joshua Blewitt’s Sporting Experiences. London: Blackett, 1893.

The Little Child’s Fable Book. London: Griffith & Farran, 1868.

London Society (1866 –74).

Once a Week (1866–71).

Punch (1866–1878).

Rooper, George. Flood, Field and Forest. London: Isbister,1874. Co-illustrated with John Carlisle.

Rooper, George. The Fox at Home and Other Tales. London: Hardwicke & Bogue, 1877

Wheelwright, Horace W. Sporting Sketches at Home and Abroad. London: Warne & Co., 1866

Created 19 March 2024