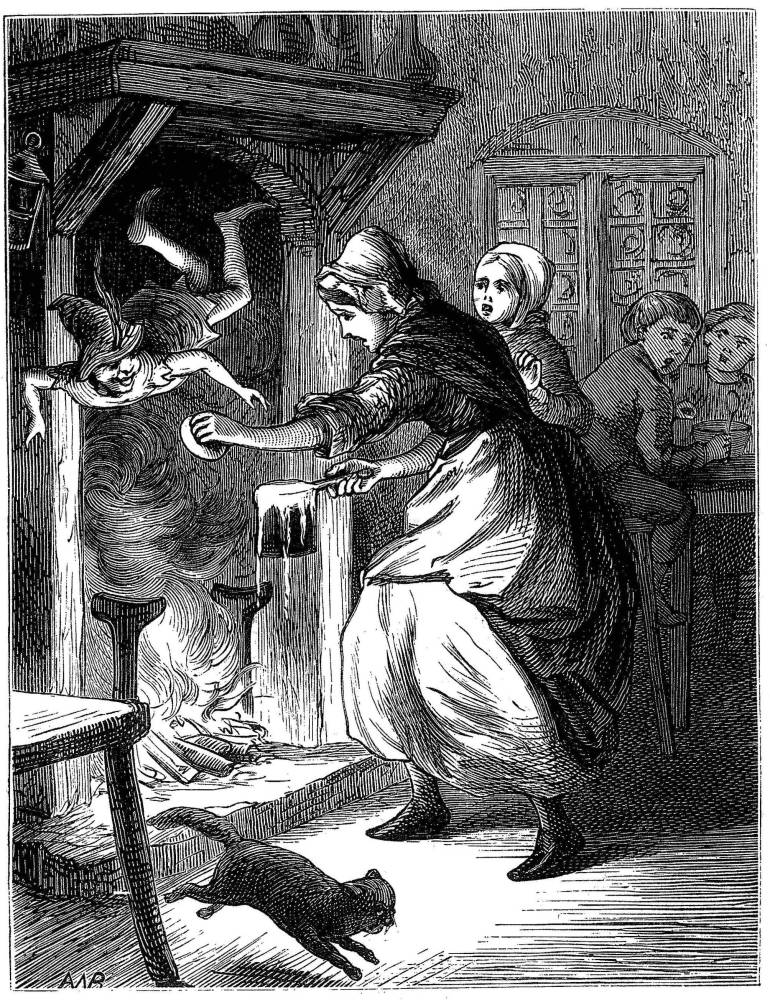

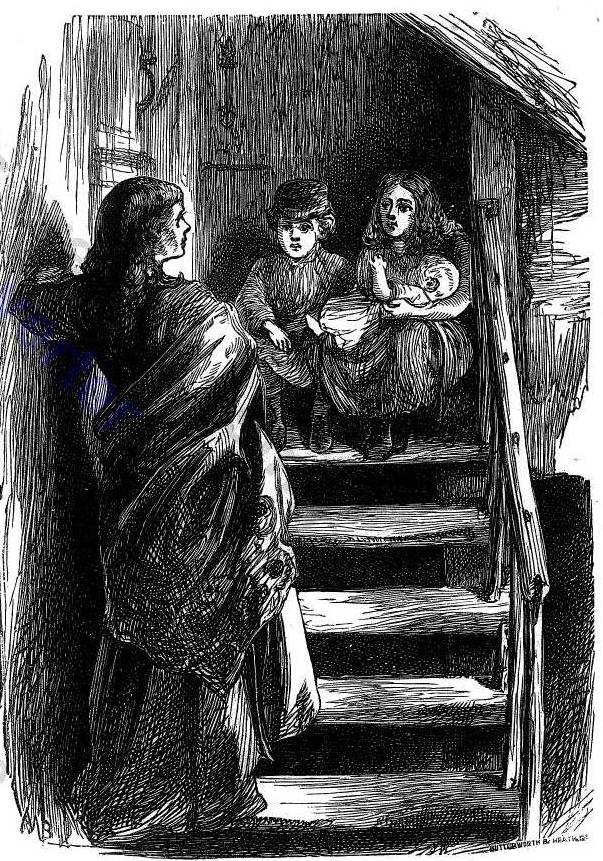

Three illustrations by Bayes: Left to right: (a) The Hillman and the Housewife. (b) A True Story. (c) Hope Deferred [Click on these images for larger pictures..]

Unlike Ruskin, most Victorians believed that fairy tales had an educational or didactic purpose. As Ewing explains in Old Fashioned Fairy Tales, fairy tales were a ‘valuable literature for the young … Like proverbs and Parables, they deal with the first principles under the simplest forms’ and

Convey knowledge of the world, shrewd lessons of virtue and vice, of common sense … They treat, not of the corner of the nursery or a playground, but of the world at large, and life in perspective; of forces visible and invisible; of Life, Death, and Immortality [p.vi].

Such lessons are clearly enacted in the stories by Andersen and Ewing, though Bayes’s designs for these texts could not be viewed as explicit pieces of moralism. Yet as an educationalist and self-improver Bayes did have a strong interest in the notion of visual teaching. This didacticism is applied to the explicit teaching of moral behaviour, as it is enshrined in a series of biblical pieces such as The Boys of Holy Writ (1865), in Kind Words, and in the social realism of Hesba Stretton.

Acting as a teacher in images, Bayes uses his design to interpret the written information in the most unambiguous form. This strategy is notably applied in his treatment of the Scriptures. In the words of H.W. Dulcken in the Preface to Golden Light (1865)

the endeavour has been to tell each story in simple pictures and in simple words – to bring the incident treated of as plainly as possible before the reader; that the woodcuts may not only please the eye, but also be of real use in explaining the meaning of the text.

In practice, Bayes presents a series of vivid images of the Scriptures that omit all inessentials. Although most of his drawings on wood are detailed with worked surfaces, in Golden Light he visualises the stories in a series of bold, simplified outlines in the manner of Pickersgill. There is barely any particularization of objects or textures; light effects are kept to the minimum; and draperies and faces are generalised. Instead, he focuses upon the narrative and its emotional content by deploying monumental figures and simplified gestures. In ‘Building the Ark’, Noah’s direction of his sons’ is reduced to its fundamentals: Noah points with an upraised finger while the other figure looks up at him (p.15). This approach is developed throughout the book, achieving a grandeur and simplicity which gives the Scriptures an impressive directness.

Far subtler is his teaching of moralities directly connected to the realities of modern life. Bayes’s appeal to his viewer’s conscience is powerfully enacted in books such as Inez and Emmeline; or, The Adopted Sister [1867], Lily and Nannie at School: a Story for Little Girls [1868], and The Cottage on the Shore, or, Little Gwen’s Story [1870]. His most sustained work, though, was for Hesba Stretton. Commencing at the end of the sixties, he illustrated several of her books directed at the improvement of children and published by the evangelical Religious Tract Society.

In Bayes’s art, Stretton found an illustrator who had observed poverty in the lives of the children he had taught and who could offer precisely the same combination of journalistic honesty and affectionate celebration that features in the pages of her texts. Notably sensitive to Stretton’s descriptions of privation, some of his drawings are hard-hitting images of struggle and despair which seem strangely at odds with their format as pictures within small-scale, decorative books for the nursery. Stretton’s stories reach their audience through careful packaging, we might say, and so do his designs.

His most effective work is Little Meg’s Children [1868]. In this book Bayes responds to Stretton’s sentimentality, showing Meg’s attempt to respectabilize her plight, washing, dressing, nursing and educating her siblings. But more telling is the representation the characters’ ragged condition and the spaces they occupy. In ‘Hope Deferred’ (p.67), the destitute, drunken woman is positioned in a shallow stage facing the juveniles as they sit at the top of rickety stairs. The claustrophobic distortions of the space and the rough detailing of the walls and stairs powerfully convey a sense of all-engulfing helplessness, as if the figures were absorbed into their setting, almost literally swallowed up by the poverty surrounding them. Redolent of Leech’s Punch images of the poor living in the Hungry Forties, Bayes shows how poverty and despair continue into the sixties and seventies. There are other traces of this compassionate interest in the poor in his work for adults, notably in Christian Lyrics (1868), and Original Poems (1868), and his imagery throughout the Christmas gift books is characterised by an emphasis not simply on Christian belief, but more on the value of compassionate loving. In these works Bayes the self-improving Methodist finds another, practical focus.

His approach is strictly educational in his illustrations for Dulcken’s Picture History of England [1865]. In Golden Light, he taught his juvenile audience by stripping away the non-essentials; here, conversely, the images enhance the writing through a process of elaboration and development. As Dulcken explains,

The illustrations … have been inserted not merely to afford amusement to the young reader, but to assist the memory; and chiefly to complete, through the eye, the explanations which the limits of the work in many cases compelled the writer to give very briefly (Preface, Picture History).

This completing is partly achieved through the augmentation of details such as costume and milieu: the bald names of the historical figures given in the text are endowed with portraits and physical presence, literally fleshing out the terse letterpress. Bayes also focuses on two main elements. One, as in Golden Light, is the visualisation of narrative, condensing complicated events into single moments. ‘Robert Setting Out for the Crusade’ (p. 49) is a prime example, which shows the character pointing eastward, his desire to journey vividly conveyed by the composition’s dynamism. Bayes further provides a schematic plan of key events, creating a series of types which epitomise British history in the form of repeating motifs and situations. Interestingly, there is a marked absence of the introspection which characterises his other work; rather, he shows the panorama of events as a cyclical pattern of confrontations, captures, submissions and battles. No political dimension is implied beyond his remit, but he does provide an effective boys’ own version of the tumultuous nature of British history when it is viewed purely in terms of its principal events, one chronological event happening after another as part of a picaresque journey through a territory of heroes and villains.

Bayes’s place in Victorian illustration

Bayes was an unusual artist. His artisan background and extreme versatility are in themselves worthy of note. Though largely self-taught, he expressed his own ideas and emphases, producing idiosyncratic designs, responding to literary texts, and publishing his work under enormous commercial pressure. By turns realistic and fantastical, dream-like and journalistic, his was a small but highly focused art. Such qualities make him an interesting figure, but in many other ways he was a typical product of his time. He was essentially a journeyman, creating images on demand as required by the voracious markets of this time, and often contributing illustrations alongside many others in the same position. Significantly, he seems to have viewed the practice of graphic design as a passing phase, and as soon as he could make a better living by painting he abandoned drawing for the page and moved on. What he leaves behind is nevertheless a substantial contribution to the evolution of book illustration of the Sixties.

Last modified 30 October 2012