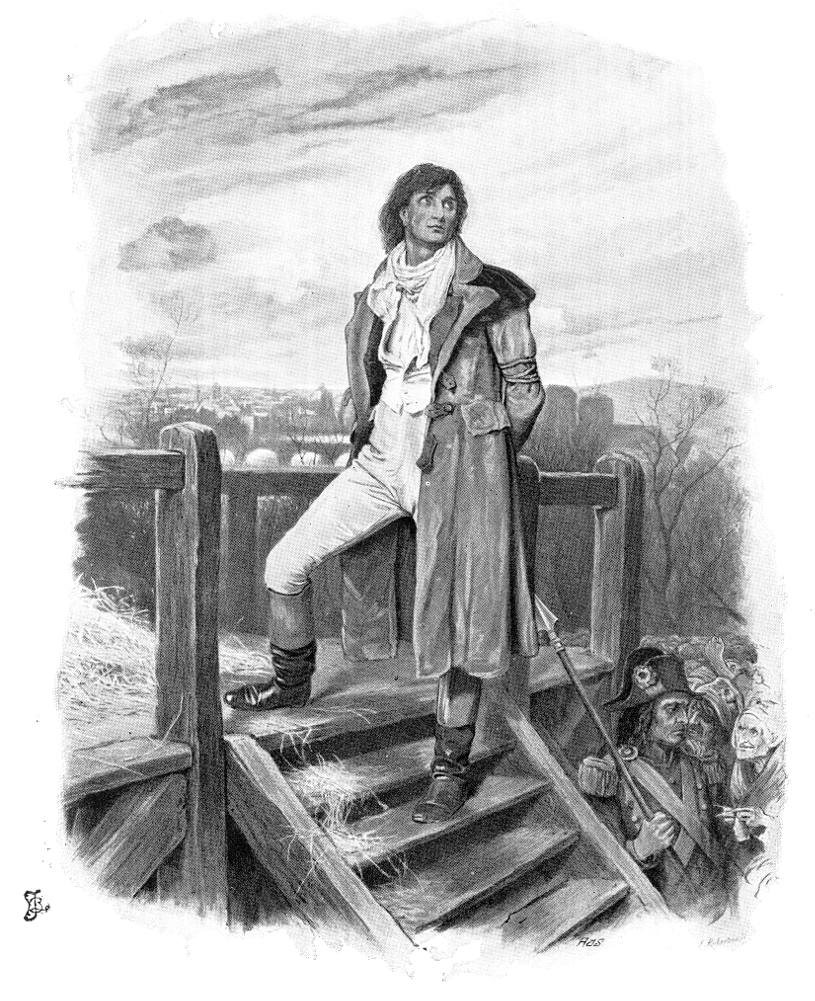

One of six lithographs in A Series of Character Sketches from Dickens, from the Original Drawings by Frederick Barnard, No. 2: "They said of him, about the city that night, that it was the peacefullest man's face ever beheld there. Many added that he looked sublime and prophetic." — A Tale of Two Cities (1884-85). "It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known." Colour plate: 10 ½ inches high by 7 ½ inches wide (36.3 cm by 19 cm), vignetted; photogravure: 16.4 cm high by 12.7 cm wide (6 ⅝ by 4 ¾ inches), vignetted. [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: A Verbal Portrait of Carton's Noble Sacrifice

She kisses his lips; he kisses hers; they solemnly bless each other. The spare hand does not tremble as he releases it; nothing worse than a sweet, bright constancy is in the patient face. She goes next before him — is gone; the knitting-women count Twenty-Two.

"I am the Resurrection and the Life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die."

The murmuring of many voices, the upturning of many faces, the pressing on of many footsteps in the outskirts of the crowd, so that it swells forward in a mass, like one great heave of water, all flashes away. Twenty-Three.

___________________________________________________________________________

They said of him, about the city that night, that it was the peacefullest man's face ever beheld there. Many added that he looked sublime and prophetic. . . . .

"It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known." [Book Three, Ch. XV, "The Footsteps Die Out Forever," 176 in The Household Edition]

Commentary: Carton's Self-Sacrifice Not Depicted until The Household Edition of 1874

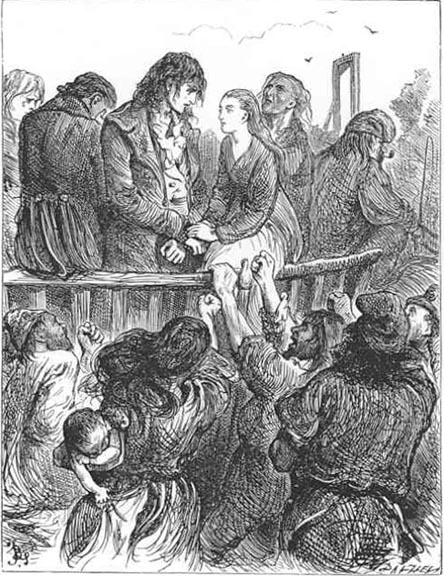

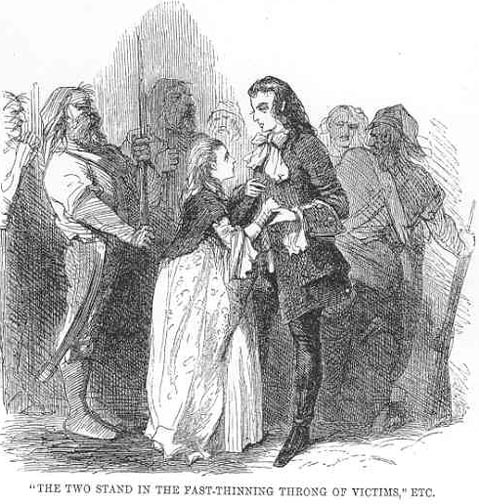

Modern readers of an edition based on the Phiz monthly numbers of 1859 are surprised that the crowning moment of the novel, with its promise of resurrection, is not among the scenes that Phiz realised in the final monthly (December) instalment. Perhaps Dickens and Phiz decided that showing Carton and the seamstress in the tumbril, the very subject of Barnard's twenty-fifth and final illustration in the Household Edition volume, would spoil the serial's suspense. However, this 1884 chromolithograph represents a considerable advance over Barnard's own The Third Tumbrel for Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 15, "The Footsteps Die out Forever," as well as that ultimate John McLenan illustration in Harper's Weekly for 26 November 1859, The two stand in the fast-thinning throng of victims, page 765.

Barnard shifts from the romance and tenderness of Carton's relationship with the hapless victim of the revolution, the little seamstress, realised with touching sentimentality in Eytinge's frontispiece Sydney Carton and The Seamstress (1867) towards the spiritual transcendence of an isolated, stoic youth prepared to sacrifice himself so that the woman he loves will not lose her husband: unrequited passion indeed!

Unlike many of the novel's other illustrators, Barnard seems to have felt no need to delineate the specifics of the scene with historical accuracy: he includes the phlegmatic executioner and his disinterested assistant, but does not sketch in the urban backdrop or even the guillotine. Like Furniss in his 1910 frontispiece, Barnard draws the reader's eye to the face and form of the courageous young Englishman, facing an unjust and arbitrary fate in order to spare his beloved Lucie's aristocratic but Liberal-minded husband and ensure their future happiness across the water. Barnard, however, is able to exploit a resource that other illustrators have not had at their disposal: colour. The slightly out of focus, etherial backdrop forces the eye forward, towards the luminescent, lithe youth ascending the steps where he will face the guillotine. However, his gaze is directed heavenward, but not so much towards the possibility of an afterlife as towards the prospect of a better world for humanity, as Dickens once called the United States, "the Republic his Imagination."

Whereas McLenan's visualization of Carton's final moments is embedded in the very passage on the page of Harper's, Eytinge's and Furniss's images as anticipatory frontispieces are separated from the textual passage realized as they remind the reader of the trajectory of the story, highlighting not merely Carton's self-sacrifice but his development as a character from dissipated wastrel to romantic hero. There is no such anticipatory attitude on the part of Barnard's viewer here, a viewer who has undoubtedly read the novel long before and now attempts to synthesize that earlier reading with Barnard's reinterpretation of the tragic hero who transcends the dire circumstances of self-sacrifice and execution.

His gaze seems rather towards the future, then, rather than towards Heaven. We are barely aware of the mob at the foot of the scaffold; it is as if Barnard has deliberately diminished both the size and significance of the blood-thirsty assemblage to focus on the slight figure in close-fitting, off-white trousers and neckcloth. Against the skyline is a dimly outlined fortress somewhat reminiscent of the Bastille, which would be an obvious anachronism here. Located in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, the notorious prison was demolished, and subsequently replaced with the Place Bastille. By November 1789 most of the fortress had been destroyed, and would not have been available as a backdrop for Carton's execution. Presumably, Carton was one of those 2,498 persons guillotined in Paris during the Revolution: 1,119 were executed on the Place de la Concorde, 73 on the Place de la Bastille, and 1,306 on the Place de la Nation. Significantly, Barnard has omitted both the little seamstress and, as noted above, the guillotine itself.

Relevant Illustrations for this Novel (1841 through 1910)

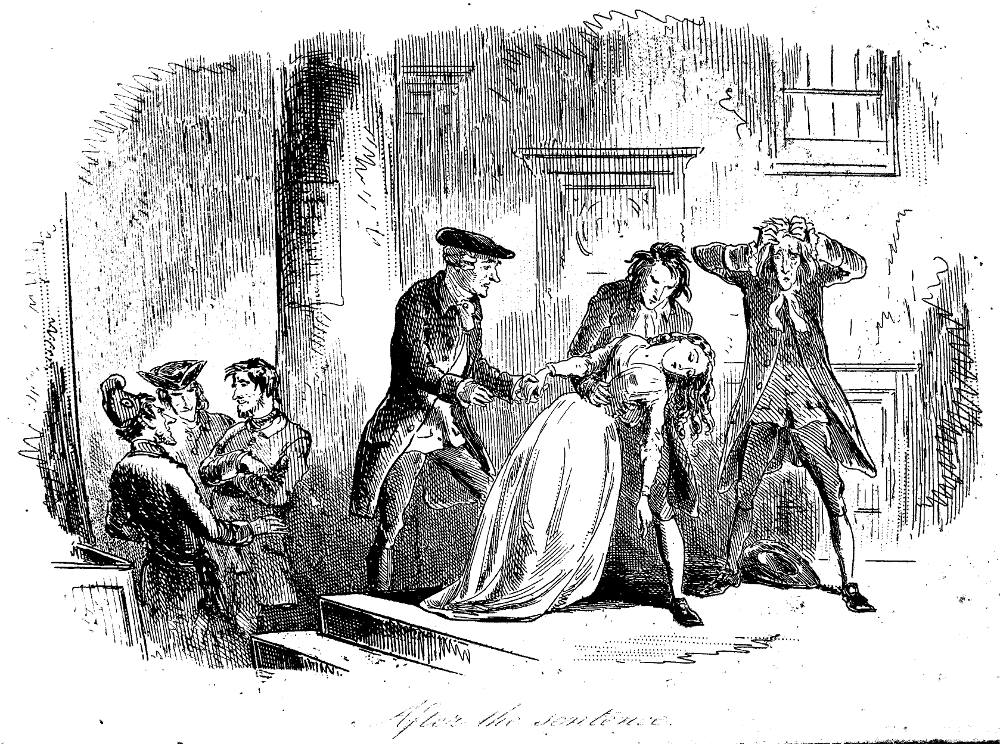

Left: Phiz's second engraving for the December 1859 monthly number, After the Sentence, realizes Lucy's reaction to Darnay's death sentence, but hints at no substitution. Centre: Fred Barnard's Household Edition composite woodblock engraving "The Third Tumbrel shows the hero's being transported to the site of the mass beheadings (1874). Right: John McLenan's climax to his extensive series of sixty-four illustrations for thirty-two weekly numbers in Harper's Weekly: The two stand in the fast-thinning throng of victims, 26 November 1859 (page 765).

Left: Harry Furniss's initial illustration emphasizes the importance of the climactic scene on the scaffold: Sydney Carton on the Scaffold (1910); right: A. A. Dixon's front wrapper (Carton on the scaffold) (1905).

Additional Resources: Other Series of Illustrations, 1859-1910

- Some Discussions of Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859) — the last Dickens novel Phiz Illustrated

- A Note on Phiz's Wrapper Design for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) in Monthly Serialisation

- Phiz's original serial illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- John McLenan's serial illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- A. A. Dixon's illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

- Harry Furniss's illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1910)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "'Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) Illustrated: A Critical Reassessment of Hablot Knight Browne's Accompanying Plates." Dickens Studies. 33 (2003): 109-158.

Barnard, Fred. Character Sketches from Dickens. (16 photogravure illustrations) London, Paris & Melbourne: Cassell, 1885.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VIII.

________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly. (24 September 1859): 621; (5 October 1859): 699; (29 October 1859): 701; (19 November 1859): 748.

________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. XIII.

________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VIII.

________. (1859). A Tale of Two Cities, ed. Andrew Sanders. World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

________. A Tale of Two Cities (1859), ed. George Woodcock. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

Sanders, Andrew. The Companion to A Tale of Two Cities. London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

A Series of Character Sketches from Dickens, from the Original Drawings by Frederick Barnard, Being Facsimiles of Original Drawings by Fred. Barnard. Series 1: Mrs. Gamp, Alfred Jingle, Bill Sikes, Little Dorrit, Sydney Carton, and Pickwick. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1884.

Created 7 February 2025