Images and caption material © copyright The Fine Art Society, London, with Haslam & Whiteway Ltd. The Fine Art Society has most generously given its permission to use information, images, and captions from its catalogues in the Victorian Web. This generosity has led to the creation of hundreds and hundreds of the site's most valuable documents on painting, drawing, sculpture, furniture, textiles, ceramics, glass, metalwork, and the people who created them. The copyright on text and images from their catalogues remains, of course, with the Society. Formatting, and commentary following the mages, by Jacqueline Banerjee. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

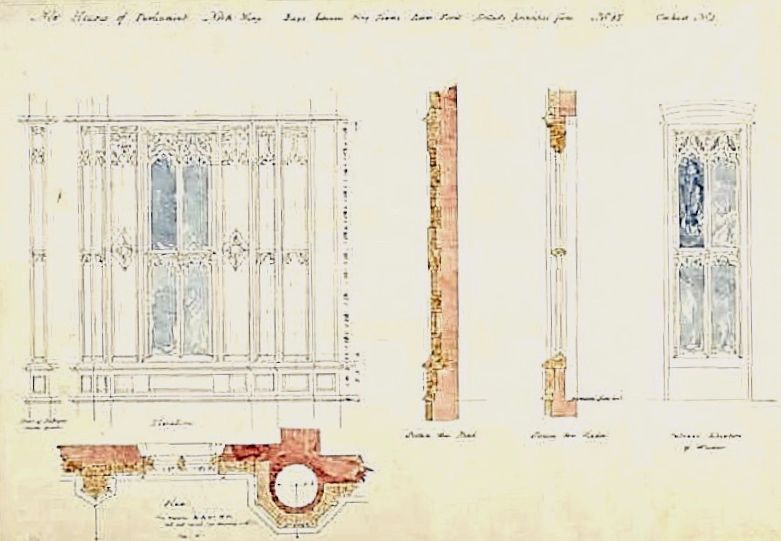

The New Houses of Parliament: North Wing, Bays Between Wing Towers, River Front: details of Principal Floor, Drawing No 85, Contract No 3. c.1840. Sir Charles Barry (1795–1860) and Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852). Pen and ink and watercolour, extensively inscribed, 28½ x 20 inches (72 x 50.5 cm).

The New Houses of Parliament: Details of Centre Portion, Central Oriels. Drawing No 167, Contract No 3. Westminster, 16 December 1840. Barry and Pugin. Pen and ink and watercolour, extensively inscribed and dated, 21 x 29 inches (53.5 x 75 cm).

It is wonderful, and instructive, to get a glimpse of the new Palace of Westminster at the planning stage. Pugin was in London on the evening of 16 October 1834, and, as is well known, was delighted to see the old palace go up in flames. The fire caused by burning old tally-sticks in the House of Lords furnace seemed to him positively heaven-sent: "a vast quantity of [Sir John] Soanes mixtures & [James] Wyatts heresies have been effectually consigned to oblivion," he crowed, "oh it was a glorious sight to see his composition mullions & cement pinnacles & battlements flying & cracking..." (42). Indeed, the old palace had been "a glorious mess," aptly described as "a ramshackle, higgledy-piggledy, degraded but monumental collection of individual buildings and artworks which over the centuries had formed a conglomeration of spaces to which human beings had been forced to adapt, rather than the other way round" (Shenton 2-3). Now there was a chance to start afresh on "true principles."

This was a chance that came directly to Pugin when two of the entrants for the competition, Charles Barry (1795-1860) and James Gillespie Graham (1776-1855), both turned to him for help as their draughtsman. The new complex was to be in the Gothic or Elizabethan style, in keeping with Westminster Abbey and its Henry VII Chapel. Barry, as again is well known, was a classicist, and this stood him in good stead as far as the generalities went, particularly as to the use of space. His would truly be "a functional secular palace" with all the necessary "practical arrangements" (Wilson 4) that had been lacking before. But his entry also carried the day over ninety-six others because of the minutely detailed drawings (like those above) that were submitted with it. Pugin's contribution was therefore crucial from the very start, and then at every future stage. "The estimate drawings set the pattern for their collaboration. Barry would outline what he wanted, Pugin would send back designs, Barry would either accept them or, more usually, ask for alterations...." (Hill 167).

Barry remained in charge, as Benjamin Ferrey (1810-80), Pugin's fellow-pupil, good friend, and first biographer generously accepts:

Although unquestionably Pugin's knowledge of mediaeval detail was superior to that of any other person of his day, and was absolutely necessary for the conception of much as well as the effective execution of the actual work — still those who were familiar with Sir C. Barry's facility of drawing and design, cannot doubt that he possessed skill of the very highest order, and that Pugin's assistance was based on the general plan provided by Barry. [248]

This assessment still holds today, with the telling difference that Barry's skill tends to be admitted first, before giving way to warmer praise of Pugin's. For example, while Barry was responsible for the structure and plan of the whole, says Rosemary Hill, "Barry's Italianate principles — 'symmetry, regularity, and unity' — were ill-suited to a Gothic design, at least as Gothic was understood in the 1830s." Therefore, Hill continues, "[i]t was Pugin's details that gave the drawings, and later the buildings, their character. It is they which created the first and the most lasting visual impression" (167). This subtle shift of emphasis shows a fuller recognition of Pugin's vital role here. Later, in 1844, Barry invited Pugin to provide designs for all the interior detailing too, as a result of which he sent out a new "flood of drawings for every part of the building" (Wilson 7). This enormous task added hugely to Pugin's workload right up until his final breakdown and death, which it very probably hastened. "Indeed the first open manifestation of his derangement occurred in the presence of Sir Charles and his family" (Ferrey 248).

The loss of the older Palace of Westminster may have seemed a "national disaster" at the time (Shenton 4), but the new one, which echoed so much of Britian's past history with its copious heraldic ornamentation, its sculptural decoration depicting swathes of royalty and saints, and its addition of intricate and picturesque interest to impressively long regular lines — not to mention its gorgeous interiors — swiftly became our most powerful and most widely recognisable national icon.

Related Material

- The Burning of the Old Houses of Parliament

- Sir Charles Barry and the Houses of Parliament (by Charles Eastlake)

- Under Construction (1842)

- Parliament seen from mid-Thames (1859 engraving)

Sources

Ferrey, Benjamin. Recollections of A. N. Welby Pugin. London: Edward Stanford, 1861. Internet Archive. Uploaded by the Getty Research Institute. Web. 30 May 2014.

Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2008. [Review]

Pugin, The Collected Letters of A.W.N. Pugin, Vol. I: 1830-1842, ed. Margaret Belcher. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Shenton, Caroline. The Day Parliament Burned Down. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Whiteway, Michael. A. W. N. Pugin 1812-1852: An Exhibition Catalogue. London: The Fine Art Society with Haslam & Whiteway Ltd., 7-23 December 2011.

Wilson, Robert. The Houses of Parliament. Stroud: Pitkin, 1994.

Last modified 30 May 2014