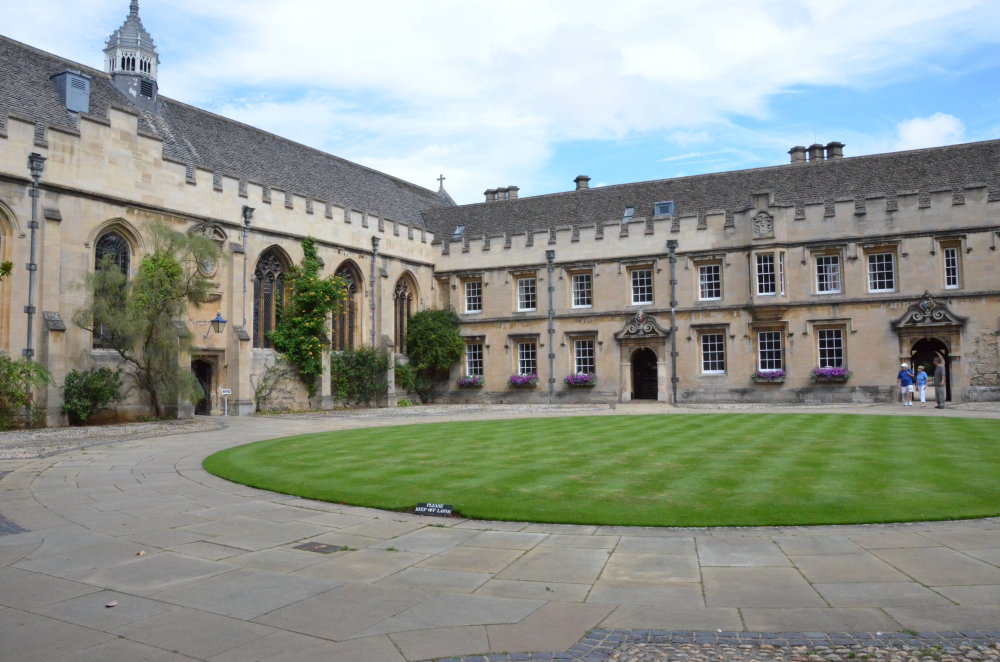

The front and W. side of the first quadrangle are remnants of St. Bernard's College” (Muirhead, 222). The doorway before which people are standing leads to Canterbury Quadrangle . Click on images to enlarge them.

St. John’s College too was an ancient haunt of monks. It was first founded a century and a half later than Worcester , under the name of St Bernard's College, by Archbishop Chichele , who was anxious that Cistercian scholars studying at Oxford should have opportunities of acquiring “humane and heavenly knowledge.” Letters patent granted by Henry VI . gave the Archbishop power “to erect a college to the honour of the most glorious Virgin Mary and St Bernard in the street commonly called Northgate Street , in the parish of St Mary Magdalene without the North Gate.”

Passing in under the gateway, which with its statue of St Bernard has not been altered since the days of the founder, we find ourselves in the original quadrangle , the south and west sides of which are occupied by the ancient lodgings of the monks, the dormer windows only having been added after the Restoration. On the left or east side are the hall, which is the old refectory of St Bernard's, built in 1502, and the chapel finished in 1530 , both of which have been considerably restored. The vaulted cellars, entered through the buttery, opposite the hall door, are part of Chichele's work.

When Henry VIII. suppressed the monasteries he caused the college to be closed and added its lands to those he had granted to his newly founded college of Christchurch. In the time of Queen Mary, however, the property was bought up by Sir Thomas White, a wealthy and generous Merchant Tailor, sometime Lord Mayor of London, who restored the deserted buildings and refounded the college under its present name of St John the Baptist’s. Tradition relates that he was told in a dream to found a college close to an elm-tree having three trunks , and that the tree in question was still pointed out in the president's garden at the The new founder liberally endowed the college and drew up for it , with the utmost care , a set of statutes, his chief aim being to ensure the peace and mutual loving kindness of the community, which consisted of a president and thirty fellows and scholars. . . . He was buried beneath the high altar in the chapel with great pomp and cere mony . After his death the college fell upon evil days. Money was lacking, for the founder' s generosity had exhausted his resources, and difficulties arose from the change in the religion of the country on the accession of Elizabeth. Many fellows refused to conform; some fled to the Continent, others died in gaol; but those who remained were patient and loyal, and their steadfastness won them friends. Rich merchants gave them money, notable men sent them their sons, gradually the college grew to be regarded as one of the most important in the university, and when James I. ascended the throne few colleges could boast so many members evidently destined to distinction, fore most among them being the future Archbishops Juxon and Laud.

The latter first came into prominence as leader of the opposition to the Calvinist doctrines under the sway of which the university was at this time; and during a certain period it was regarded as heresy to speak to him or even to salute him in the street. He had, however, influential friends, and through them obtained various preferments . In 1610 he was elected president of St John's, but not without some show of hostility on the part of certain fellows, one of whom snatched the nomination papers off the altar, where, as was customary, they were laid, and tore them in pieces. Sermons were preached against him in St Mary's: “He was fain to sit patiently and hear himself abused almost an hour together, being pointed at”; but the King favoured him, made him Royal Chaplain, created him Dean of Gloucester, Bishop of St David's, and in 1630 Chancellor of the University, Dr Juxon meanwhile replacing him as president of St John's.

The Garden Quadrangle and other green spaces. Click on images to enlarge them.

The college was now prospering greatly, large sums of money and gifts of land were steadily coming in, and the finishing touch was put when Laud began to “buildat St John's in Oxford, where I was bred up, for the good and safety of that college.” To him the college owes the second or Canterbury quadrangle, so called because by the time it was completed in 1636 Laud had been made Archbishop of Canterbury. It is entered by a passage with a fine vaulted ceiling leading from the first quadrangle, and the library occupies its south and east sides. When all things were in readiness Charles I. and his Queen signified their intention of visiting the college, and great preparations for their enter tainment were made. Laud himself describes the festivi . ties, which included “a fine short song fitted for them as they ascended the stairs,” a dinner at which “the baked meats were so con trived by the cook, that there was first the forms of archbishops, then bishops, doctors, etc ., seen in order, " and a play which was “merryand without offence”; “and,” the Archbishop continues, “no man went out at the gates, courtier or other, but content; which was a happiness quite beyond expectation .”

Left two: Muirhead'sBlue Guide comments “the famous colonnades and the charming Garden Front form an interesting blend of the traditional Gothic of Oxford with the classical style of Italy” (223). Right: Looking through the gate from the garden back through both quadrangles in the direction of St. Giles.

After doing all he could for his own college Laud turned his attention to the university itself, and drew up a series of statutes for its reform, which was so much to its advantage that Sir John Coke wrote to him : “You . . . have made this university, which before had no paragon in any foreign country, now to go beyond itself and give a glorious example to others not to go behind .”

The Civil War put an end to this period of peace and prosperity, teaching and learning ceased, and arms were the order of the day. St John's in common with the other colleges melted down its plate for the benefit of the King and subscribed sums of money to maintain his army. The Commonwealth found it poverty, stricken and neglected, and not until the Restoration was it possible to carry Laud's last wish into effect and bury him “in the chapel of St John Baptist College under the altar or communion table,” where he lies between the founder and Archbishop Juxon. Even in a loyal city like Oxford, St John's was remarkable for its devotion to King Charles, and one benefactor left a sum of money for the endowment of a series of loyal lectures; two to be delivered on “the day of the horrid and most execrable murder of that most glorious prince and martyr,” “setting forth the barbarous cruelty of that unparalleled parricide”; the third on the “day wherein Rebellion did appear solemnly armed against Majesty”; and the fourth on the date of Charles II.'s return, “setting forth the glory and happiness of that day.”

Links to Related Material

Click on images to enlarge them. Photographs, formatting, and text by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Great Britain. Ed. Findlay Muirhead. “The Blue Guides.” London: Macmillan, 1930.

Lang, Elsie M. The Oxford Colleges. London: T. Werner. HathiTrust online version of a copy in the University of Michigan Library. Web. 8 November 2022.

Last modified 8 November 2022