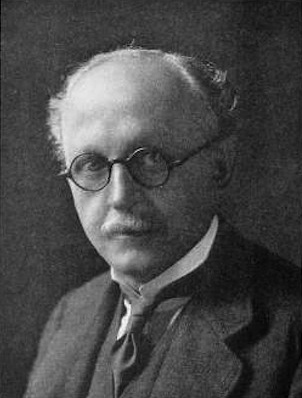

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens — yes, named after the painter, a family friend — was born in London in 1869 and died there of cancer seventy-five years later. In that time, I wonder, did he design more buildings and memorials than any other architect in history? Some years he had half a dozen on the go at the same time, each in his own distinctive style - which changed from the Arts and Crafts Movement in the nineteenth century, to a more classical taste in the early twentieth, to a blend of European and Indian in the 1920s, and to what one biographer called "simplified Queen Anne." Among his buildings are the British Embassy in Washington, the Viceroy's House in New Delhi, Castle Drogo in Devon, churches, office blocks, domestic houses, cemeteries, monuments, memorials and, not least, the Cenotaph — a simple oblong of Portland stone — in Whitehall.

He was the tenth of thirteen children in a large Victorian family but too delicate to go to school. Not going to public school, he said, left him shy with committees and officials but taught him to look and think for himself - for example as a small boy he devised his own home-made sketchpad out of a square of plain glass. He looked at buildings through it while tracing their outlines on the glass with sharpened sticks of soap. Professionally, he began studying architecture at the South Kensington School of Art (now the Royal College) between 1885-7. The course was never finished and next year he went as a paying pupil to the firm of Ernst George and Peto before setting up his own practice when he was still only nineteen. In 1889 he was commissioned to build a small private house, Crooksbury, near Farnham in Surrey. Soon, his style was influenced by Philip Webb and William Morris. Now, too, he met Gertrude Jekyll, the garden designer. Together they designed and built scores of houses with distinctive Jekyll gardens, including her own home, Munstead Wood. Often their results were published — and publicised - in Edward Hudson's magazine Country Life (still going strong, still featuring country houses). Later Lutyens restored Lindisfarne Castle, on Holy Island off the Northumberland coast, which was owned by Hudson at the time.

By 1900 he'd come under the influence of Norman Shaw and the English Renaissance style. By now, as well, he was also designing office buildings. In 1908 he was the architect for the new Hampstead Garden suburb, designing the civic centre and two churches. In 1909 he was a consulting architect at the international exhibitions in Turin and Rome — his Roman building is today the British School in that city. During these years, too, he was in South Africa designing the Jo'burg Art Gallery and Rand war memorial. In 1910 he was asked to design England's newest castle — Castle Drogo in Devon. It took twenty-two years to build and is now owned by the National Trust.

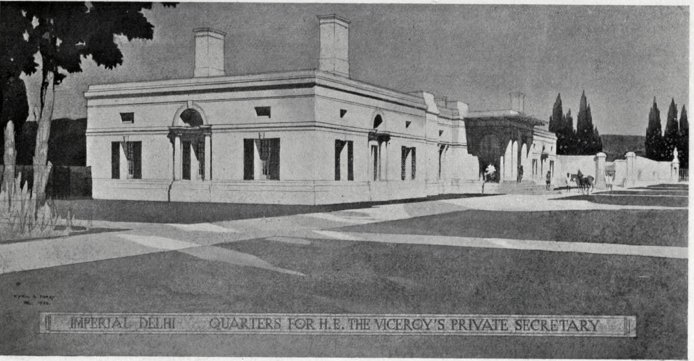

Left to right: (a) Staff Quarters on Axial Line Leading to Government House, Delhi. (b) Quarters for H.E. the Viceroy's Private Secretary. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

In 1912 he was part of the Planning Commission which built New Delhi on a green field site as the new seat of government in India. Lutyens designed the Viceroy's house (among others). Today it's the President's Residence. For it he invented yet another a new style of architecture — part Indian, part European - which he used later for Campion Hall, a new college in Oxford. His co-architect was Sir Herbert Baker, a man he'd first men in Peto's office back in the 1880s. There was a serious professional falling out between the two men, apparently over the siting and approaches to Viceroy House. He had, Lutyens said, met his Bakerloo. (A joke which makes more sense if you know that the Bakerloo is a London underground railway line.)

Trafalgar Square Fountain

Towards the end of the Great War he began working for the Imperial War Graves Commission, designing monuments, cemeteries, and at least fifty memorials such as the Beattie and Jellicoe fountains in Trafalgar Square. Perhaps his two best known works are the Cenotaph in Whitehall and the Thiepval Arch in France, a memorial to those men of the Somme who have no known grave (more than 72,000 of them). It's said the Cenotaph took him only a few hours to design: and it issimple, though it is has no straight lines and therefore has a flowing quality. Originally he wanted stone flags but was over-ruled; they are cloth to this day. At Thiepval the Last Post is sounded by a solitary bugler every evening at sunset in memory of the fallen.

Britannic House. North-west side of Finsbury Circus, London EC2

He began the 1920s with major office developments in London — including Britannic House for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now BP) and three new banks for the Midland (now amalgamated out of existence). He continued his great country houses, and added a palace in India for the Nizam of Hyderabad. The one big commission that got away was the Roman Catholic cathedral in Liverpool. Work began in 1933 but was abandoned during the war with only the crypt at all finished — a measure of its planned size: it would have been taller than St Peter's in Rome, twice as big as St Paul's in London A model in Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery is itself said to be world class.

In 1897 he'd married Emily, a daughter of the Earl of Lytton, a former Viceroy of India. They had five children. One of them, Mary, left a personal account of her father and mother — who, it seems, had little in common: not even their reading habits (he never read at all, other than The Times crossword). She was no socialite and was happy for his clients to entertain him without her. He was, his daughter said, more at ease this way, free to re-tell old jokes and flirt. (She noted the paradox between his shyness and his ability to twist clients around his little finger.)

Because he never read other people's opinions, his daughter said, his own thoughts were always original. Designers, he once wrote in a letter to his wife, should never read poetry: "there is in the hearts of men a natural desire for poetry. If read it is easily acquired and satisfied. If not read you have to get your eventual quota of it through, and in, your work and not be doped by other people's adjectives."

As a man, he replaced his boyhood glass and soap sketchpad with paper and pencils which he carried everywhere. On the spot he could draw details of a building for clients or entertain them with an instant cartoon. Guests in India were given chalks as they sat down to eat at a table with a large circular black board in the middle. He also became famous for his puns though the one he made in the Garrick Club when served a plate of fish ("this is the piece of cod which passeth understanding") is not, I think, exclusively his. One cartoon was of Gandhi riding a camel with the caption: "You should see Mysore."

He particularly liked designing children's nurseries — they brought out his child-like imagination, his daughter said, and lightness of touch. The nursery floor in the vice regal house in New Delhi was laid out in red and black squares as a built-in games board on which children could play chess or chequers. At least two nurseries in England had floor level windows to give the not-yet-walking a private outlook on the world. At least one nursery was circular so that no child, however naughty, had a corner to stand in — a Victorian punishment probably no longer practised.

Lutyens was knighted in 1918, elected a Fellow of the Royal Academy in 1921, and awarded the Order of Merit twenty years later. He died on New Year's day, 1944. Harold Nicholson's wrote an obituary: "Lutyens possessed the faculty of making everybody feel much younger. He adopted an identical attitude of bubbling friendliness whether he was talking to a Queen Dowager or a cigarette girl, a Cardinal or a schoolboy." Or as Kipling put it he could "walk with kings" yet "keep the common touch."

Related Material

References

Brown, Jane. Gardens of a Golden Afternoon. Allen Lane. London, 1982

Butler, A S C. The Architecture of Sir Edwin Lutyens, 3 vols. Country Life & Scribners. London and New York, 1950

Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 1975

Hussey, Christopher. The Life of Sir Edwin Lutyens. Antique Collectors' Club. Woodbridge, Suffolk. 1989.

Website of the Lutyens Trust: www.lutyenstrust.org.

Last modified 20 May 2013