iscovered on November 8, 1895 by German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen, X-rays not only revolutionized science and medicine and captivated the Victorian imagination, but they also heralded cultural shifts that would signal the end of the Victorian era. The nineteenth century was defined by rapid scientific and technological progress. By the 1890s, daily life had been transformed by railroads and telegraphs, and public fascination with invisible forces such as electricity and magnetism was strong. The invention of photography had already changed how people viewed the world, so when Roentgen published the findings of his experiments on January 1, 1896, Victorians were primed for a science and a technology that promised to reveal the hidden inner workings of their bodies and of the world.

Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays was unplanned. In 1895, the German physicist had been experimenting, as were other scientists, with cathode rays, or streams of electrons produced in vacuum tubes. While working with them one day, Roentgen noticed a screen across the room begin to fluoresce. Curious, Roentgen began to place objects between the vacuum tube producing the cathode rays and the screen, and observed that shadows began appearing on the screen. Fascinated by this result, Roentgen placed a series of household objects in the pathway, including letters in sealed envelopes, books, weights, and even his hunting gun. For weeks, Roentgen conducted his experiments in secret. On December 22, 1895, Roentgen asked his wife, Anna Bertha, to place her hand in the pathway. When the skeletal image appeared, Anna Bertha famously exclaimed, "I have seen my death!" Her reaction heralded the discovery as prophetic, and in many ways it was, as Roentgen’s X-rays would open a new era of science and medicine. When Roentgen published his findings in the journal Nature on January 1, 1896, the X-ray of Anna Berthe’s hand was the first human X-ray presented to the public.

Anna Berthe's Left Hand (1895), photograph by Wilhelm Roentgen, courtesy of the Wellcome Collection. Click on the image to enlarge it.

A true scientist, Roentgen called his discovery X-rays because he did not know what element comprised the rays. They were an unknown, an "x," which is the mathematical sign of an unknown variable. A humble man, Roentgen never patented his discovery, believing that it belonged to the world. His choice to publish an X-ray of a human hand made the medical applications of his discovery immediately evident. In his publications, Roentgen also included instructions for making his X-ray machine, a device that could be constructed from readily available materials, leading scientists — amateurs and professionals alike — to construct their own machines for experimenting.

Roentgen’s discovery was not without negative consequences. The first generation of X-ray pioneers were unaware of the dangers that radiation posed, and many X-ray scientists and X-ray machine operators suffered physical injuries, including vision problems and radiation burns often leading to cancerous carcinomas, amputations, and sometimes death. Thomas Edison's assistant Clarence Dally is often considered the first person to die from radiation exposure caused by X-rays. After Dally’s death in 1904, Edison ceased all experiments with X-rays ("C.M. Dally Dies a Martyr to Science"; "Edison Fears Hidden Perils of the X-ray").

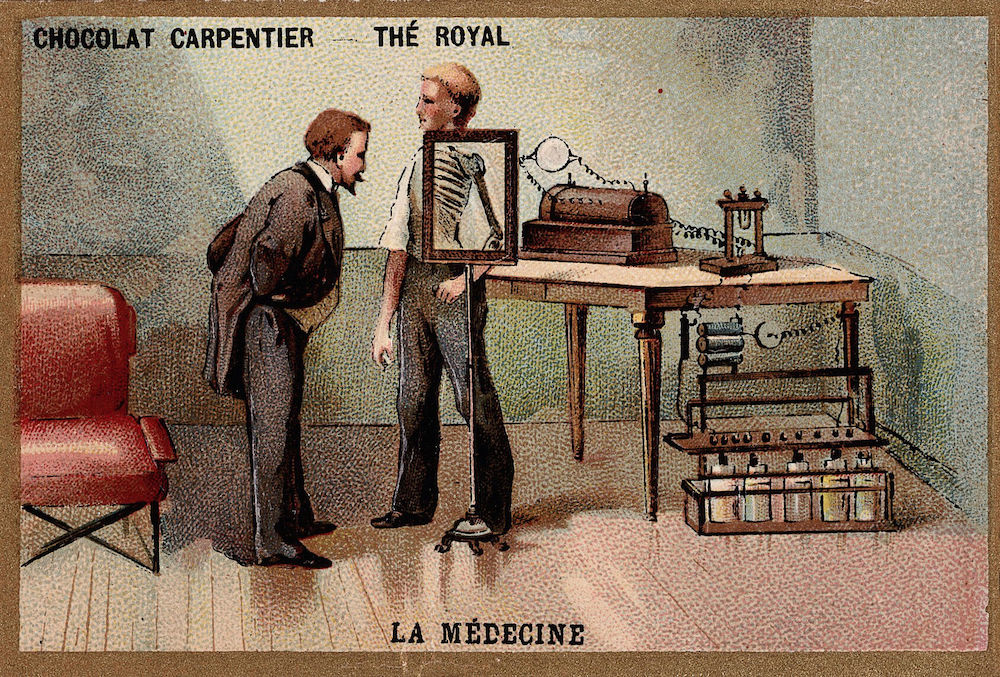

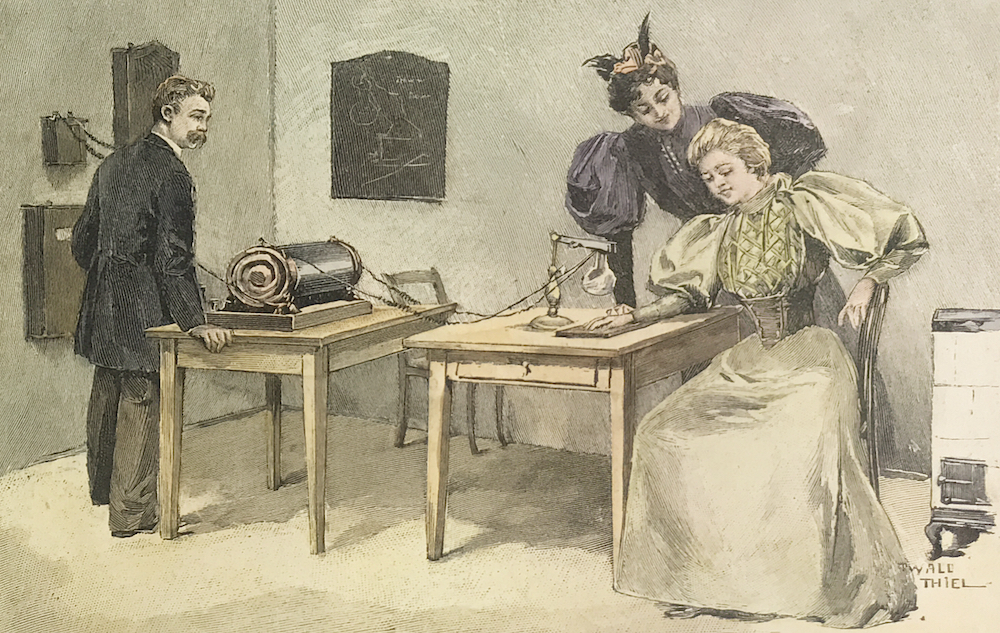

Left: La Médecine (1896/1900), chromolithograph showing Wilhelm Roentgen looking into an X-ray screen placed in front of a man's body and seeing the ribs and the bones of the arm, courtesy of the Wellcome Collection. Right: X-ray (1900) by Ernst Otto Ewald Thiel, courtesy of the Internet Archive. Click the images to enlarge them.

Despite their dangers, there was no denying the significant impact of X-rays on every facet of daily life. Within weeks of their announcement, X-rays were being used by hospitals to diagnose fractures and locate bullets, and in museums to study ancient remains. In April 1896, Smith v. Grant, the first court case to use X-rays as evidence of medical malpractice and negligence, was presented and won on the basis of the X-ray evidence. "X-ray mania" came to describe the cultural responses of 1896 and 1897 to X-rays that resulted in songs, poems, and advertising. Advertisers used the term "X-ray" to market everything from headache tablets and golf balls to laundry detergent and whiskey.

The X-ray became the symbol for making invisible, visible. Advocates of temperance hoped X-rays would show alcohol's damage to the human body, while members of the Spiritualist movement hoped X-rays would reveal the human spirit. X-rays resonated strongly with the Victorians' interest in spirituality and the supernatural. H.G. Wells, for example, was inspired by the supernatural appeal of X-rays to write The Invisible Man (1897), a speculative work of science fiction that explores the psychological and metaphysical implications of a body made first transparent and then altogether invisible. Through his fiction, Wells anticipated ontological debates about identity and the nature of reality that would later come to characterize literary modernism.

The discovery of X-rays in 1895 also coincided with the Lumière brothers' early cinematography. Several early films explore both the Gothic and the comedic potential of X-rays. The most famous of these is English filmmaker George Albert Smith's The X-rays or The X-ray Fiend (1897). In this 45-second silent film, a courting couple are approached by a man carrying a large white projector box labeled "X-RAYS." The camera operator removes the camera's lens cap, and the couple are transformed into skeletons. After thirteen seconds, he replaces the lens cap, and the transformation ends. While transformed, the courting man appears much more amorous and animated; his legs jump up and down, and he grasps at the woman’s hand. When they are transformed back, the young woman stands and pulls her hand from the man's grasp, then lightly slaps him across the face before walking off screen. The man huffs and appears disgruntled. The film’s title, The X-ray Fiend, suggests that the X-rays reveal the man's fiendish nature, making visible to the audience, and presumably the woman, that which he had kept hidden. The film's tone leans towards the comedic, but the theme of danger averted is still clear. Other silent films of the era, such as Wallace McCutcheon's The X-ray Mirror (1898), in which a young woman unknowingly looks into an X-ray mirror and faints upon seeing her skeleton, and Èmile Vardannes's Un Ragno nel Cervello or A Spider on the Brain (1912), in which a spider nesting inside a person’s brain is revealed through X-rays, embrace more fully the potential Gothic horror of X-rays.

Strand-Idyll á la Röntgen (1900), postcard by an unknown artist, courtesy of The Internet Archive.

As a symbol, the X-ray embodied the Victorian era's scientific advancements, the Victorian desire to push the boundaries of human knowledge, and Victorians' deep fascination with the unseen. With their discovery, X-rays opened a pathway into the modern era's radiation technologies and later, nuclear science, as well as even more advanced imaging technologies such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). X-rays raised new questions about the limits of perception and evoked philosophical questions about identity and the unseen that heralded and shaped important scientific and cultural developments of the twentieth century.

Bibliography

Avery, Simon. "'A New Kind of Rays': Gothic Fears, Cultural Anxieties and the Discovery of X-rays in the 1890s.” Gothic Studies 17, no. 1 (2015): 61-75.

Cartwright, Lisa. Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995).

"C.M. Dally Dies a Martyr to Science," New York Times, October 4, 1904, 16.

"Edison Fears Hidden Perils of the X-rays," New York World, August 3, 1903, 1.

Glasser, Otto. Wilhelm Roentgen and the Early History of the Roentgen Rays. San Francisco: Norman Publishing, 1993.

Golan, Tal. "The Authority of Shadows: The Legal Embrace of the X-ray." Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques 24, no. 3 (1998): 437-58.

Grove, Allen. "Röntgen’s Ghosts: Photography, X-rays, and the Victorian Imagination." Literature and Medicine 16, no. 2 (1997): 141-73.

Lobdell, Nicole. X-ray. London: Bloomsbury, 2024.

Michette, Alan and Sawka Pfauntsch, eds. X-rays: The First Hundred Years. Hoboken: Wiley, 1996.

Pamboukian, Sylvia. "'Looking Radiant': Science, Photography, and the X-ray Craze of 1896." Victorian Review 27, no. 2 (2001): 56-74.

Roentgen, Wilhelm Conrad. "On a New Kind of Rays." Translated by Arthur Stanton. Nature 53 (23 January 1896): 274-76.

Scott, Charles C. "X-ray Pictures as Evidence." Michigan Law Review 44, no. 5 (1946): 773-96.

Solveig, Jülich. “Seeing in the Dark: Early X-ray Imaging and Cinema," in Moving Images: From Edison to the Webcam, eds. John Fullerton and Astrid Söderbergh Widding (East Barnet, Herts: John Libbey Publishing, 2000): 47-58.

Created 17 January 2025

Last modified 27 January 2025