Public Sculpture of Bristol, the twelfth in the excellent series on the sculpture of our major cities produced under the auspices of the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association, fully lives up to the high standards set by its predecessors. It gives a graphic account of some 200 statues, monuments and other sculptures from Virgin and Child Enthroned (1240) to Jason Lane's Greater Crested Plunger (2008).

Edward III granted a charter to Bristol in 1373 and for four centuries the port was the richest city in Britain after London. The Bristol Nails are a reminder of the days of that commercial greatness. These four brass pillars, dating from 1600-31, were used for concluding deals, hence the expression "cash on the nail" (although the authors modestly admit that the phrase "cannot be exclusively associated with Bristol"). Another sign of Bristol's prosperity is the splendid William III by Michael Rysbrack, dating from 1736 and said by Katherine Eustace to be "Western Europe's finest 18th century equestrian monument."

In the industrial era Bristol was overtaken by Liverpool and Manchester. With the resulting shortage of wealthy patrons, individual and corporate, Bristol has rather fewer monuments by leading Victorian and Edwardian sculptors than its northern rivals. In his definitive Victorian Sculpture Ben Read lists 15 works in Bristol, compared with 39 in Liverpool and 46 in Manchester. However, Bristol's sculptures are of high quality. Works by John Thomas, who was responsible for much of the architectural sculpture in the Houses of Parliament., adorn the facades of the Guildhall (1843), Lloyds Bank (1854) and the Royal West of England Academy (1857). A tobacco magnate, Sir George Edwards, joined a member of the Fry chocolate dynasty to fund Sir Edgar Boehm's Golden Jubilee statue of Queen Victoria (1888). Bristol-born James Havard Thomas executed statues of two of the city's MPs, Samuel Morley (1887) and Edmund Burke (1894), the latter commissioned by another tobacco millionaire, William H. Wills.

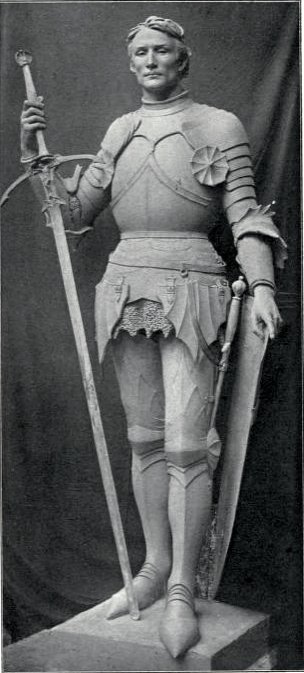

Alfred Drury's St George [Click on thumbnail for larger image and more information.]

In the first half of the 20th century Charles Pibworth, also Bristol-born, executed some remarkable bas-reliefs for the Central Library (1905). Clifton College has Alfred Drury's striking St George surmounting its South African War memorial (!904) and, rather later, William McMillan's sombre Field Marshal Haig (1931). The most prominent statue of the Edwardian era is, fittingly, Henry Poole's handsome memorial to Edward VII (1913). The authors reveal how the architect of the memorial (Edwin Rickard) "manipulated the outcome of the competition to ensure that his own preferred sculptor [Poole] gained the commission." George V was consulted about the form of the memorial and indicated that an equestrian statue would be "too militant." The book does not explain why the unveiling ceremony was performed by the Lord Mayor and not by the king, despite the fact that George V was in Bristol for the Royal Agricultural Show. He was invited to view the statue from his carriage but "did not alight."

The splendid gilded unicorn depicted on the cover of the book (see above) is not a mediaeval survival but one of a pair by David McFall (1950) on the roof of Bristol's massive Council House. The story behind the unicorns is an amusing one — when they were delivered, no one knew who had ordered them and a city official was quoted as saying "the whole thing is a complete mystery... unicorns have never been mentioned for the Council House." The local press had a field day. It later emerged that the architect of the Council House, Vincent Harris, had commissioned the unicorns from his friend McCall on his own authority. He explained that the cost fell within the estimate for the building and that he was "entitled to alter any detail that did not infringe the terms of the contract." The Council prudently accepted the fait accompli; as the authors point out, the unicorns bring "vital relief" to an otherwise monotonous building.

The unicorns marked the start of a virtual renaissance of sculpture in Bristol. The useful list at the beginning of the book records that while 102 sculptures date from the two centuries 1750 to 1949, almost the same number (95) have appeared in Bristol in the last sixty years. This reflects a national movement towards contemporary free-standing sculpture in public places from the 1960s onwards. Paul Mount's Spirit of Bristol (1970), a stainless steel abstract, linked the city's maritime past with the flight of the Concorde aircraft. Commissioned by the developers of an office block (York House), this statue is sadly neglected; neither the local authority nor the present occupants of York House admit ownership or responsibility. Another important work needing care and attention is the symbolic bronze Hand of the River God (1984) by Vincent Woropay; the fountain has not worked since it was installed and the small figure of Hercules was stolen in 1998. Action by the City Council seems long overdue.

The largest three-dimensional sculptural sculpture in Bristol is Lollypop Be-bop by Andrew Smith (2001). This imaginative work stands in front of the Royal Hospital for Children and must have cheered up thousands of youngsters over the years. The sculptor originally intended that fibre-optic lights in the coloured rings would be lit up by children pressing buttons, but this proved to be too technically challenging. Another large work giving much pleasure is Peter Randall-Page's Beside the Still Waters (1993), a massive limestone pine cone set in a circular pond in Castle Park and described as "an oasis in the heart of the city."

It must not be thought that all Bristol's more recent sculptures are abstract or symbolic. The wishes of those who prefer more traditional statues have been met by works ranging from John Doubleday's Brunel (1982) and David Backhouse's Cloaked Horseman (1984) to Lawrence Holofcener's trio of Chatterton, Penn and Tyndale (2001), Graham Ibbeson's Cary Grant (also 2001) and Stephen Joyce's Fireman (2003).

Public Sculpture of Bristol is arranged by streets, from Albert Road to Worcester Road via College Green and Queen Square, so it is ideal for those exploring the city's statuary on foot. An added bonus is a detailed account of monuments in Bristol's churches by Dr Eustace entitled Bread and Sermons. Read and enjoy.

Bibliography

Merritt, Douglas, and Francis Greenacre with Katharine Eustace. Public Sculpture of Bristol. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2010. Paperback, ISBN 9781846316388, £30; hardback, ISBN 9781846314810, £60.

Last modified 16 September 2011