This article has been peer-reviewed under the direction of Professors Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge (University of Victoria). It forms part of the Great Expectations Pregnancy Project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

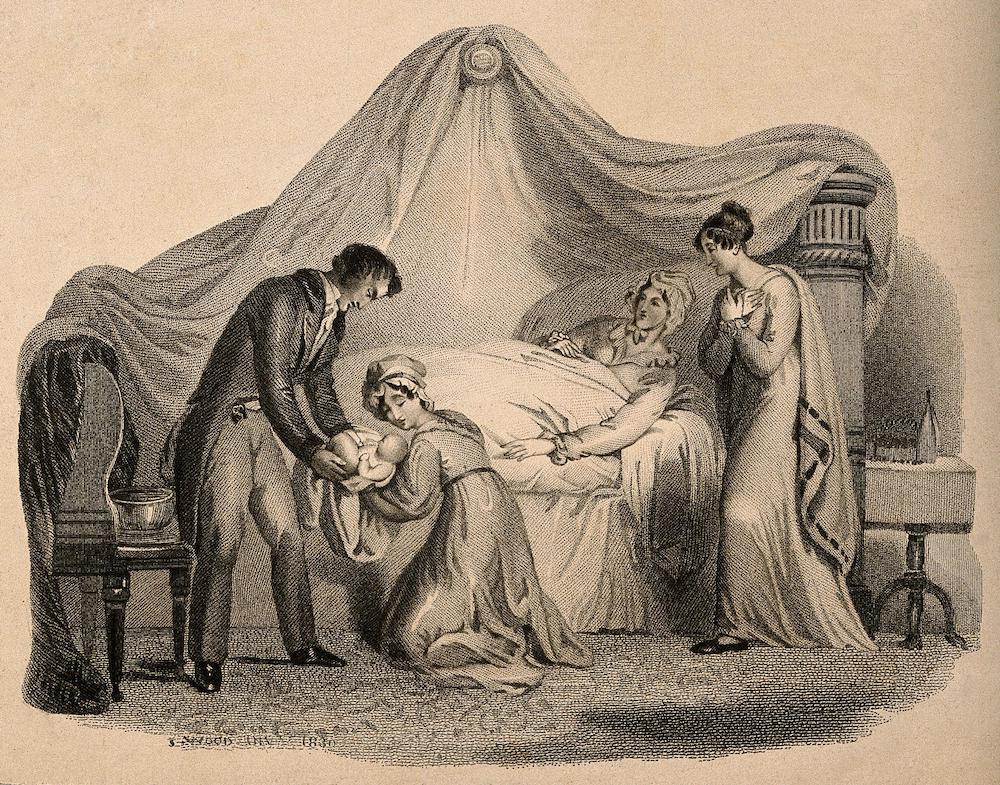

A woman in bed after giving birth. Engraving by J. Wood, 1830. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Pregnancy, childbirth and childcare would dominate the adult lives of many Victorian women. These roles were depicted by many — church and government, in prescriptive literature and novels of the period, and by medical men — as women’s most important, almost sacrosanct, duties. “A woman may consider herself a mother, not only from the birth of her child, but even from the moment of conception,” proclaimed medical author Thomas Bull, “From that important epoch her duties commence—duties amongst the most sacred and dignified which humanity is called upon to perform” (Bull 3–4; see also "Advice to a Young Wife" by Anna Niiranen).

After the mid-nineteenth century, many middle-class families began to practice family limitation (Branca; see also "Birth Control" by Lesley Hall). However, 63 percent of women marrying in England and Wales in 1860 would still bear five or more children (Ross, Love and Toil 92). Though many women expressed joy at the birth of their children, childbirth was often accompanied by anxieties about the delivery itself and the potential risks to mother and child. For poor women in particular, repeated pregnancies and deliveries, and the burden of rearing so many children, meant that childbirth was often equated with ill health and exhaustion. This essay briefly explores women’s experiences of childbirth and the significant changes that took place during the nineteenth century in terms of birth attendance and the stepping up of medical interventions in childbirth, in response in part to changing perceptions of risk.

Experiences and Risks of Childbirth

Queen Victoria, herself mother to nine children, described pregnancy and her confinements as hard and dreadful, and continued to voice her negative feelings about childbirth long after her last child was born. Writing to the Princess Royal in January 1859, Victoria reflected back on the birth of her firstborn, Prince Edward, almost twenty years previously. She described her severe pains — using the term “suffering” four times in her short letter — and commiserated on the “cruel sufferings” of her daughter during her first delivery (Fulford 159–60). Other women, however, described more positive experiences of childbirth, and Judith Schneid Lewis has argued that women of the aristocracy at least, might be well supported and reassured by their medical attendant. Emma Mainwaring reported with joy in 1848 that she had “the best and shortest labour she ever knew” (Schneid Lewis 191).

Experiences of pregnancy and birth were shaped for many women by the fear of injury during the delivery or of death in childbirth. During the 1850s, the maternal mortality rate for England and Wales was 47 per 10,000 births, which meant that around 31,000 women died in childbirth during the course of the decade (Loudon, Death in Childbirth, 14–15). The majority of these deaths resulted from puerperal fever, a highly contagious disease, which tore through maternity hospitals, as well as afflicting many women confined at home. With no discrimination between the social classes, this “exceptionally cruel and dreadful disease” openly horrified medical practitioners, as “a sort of desecration for an accouché to die” (Meigs 576).

Meanwhile, many infants were stillborn or perished in their first year of life and only towards the end of Victoria’s reign did levels of infant mortality begin to dip. While the birth rate fell by 14 percent in England and Wales between 1876 and 1899, over the same period infant mortality increased from 146 per thousand births to 156, a rise of 7 percent (Dwork 4–5). Though figures varied across the country and many rural areas had dreadful rates of infant mortality, large cities with poor housing and sanitation tended to fare particularly badly. In response to the high incidence of infant deaths, Ellen Ross has described the attachment of poor London mothers to their newborn infants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as “tentative.” Yet Ross also pointed out that many mothers saw infant care as a major responsibility and babies were likely to get a good deal of attention and affection if they thrived, were held constantly and nursed on demand, and included in family and neighbourhood activities (Ross, Love and Toil, 184, 186; Ross, Labour and Love, 80)

Four young children play together in a kitchen as their mother looks on holding a baby. Engraving by Lumb Stocks (1812-92) after A.H. Burr. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Midwives

While medical men increasingly portrayed themselves as best able to manage childbirth, for poor women attendance by local midwives at their confinements would remain the norm, and in 1870 most births were still midwife attended in large manufacturing towns. In London up to 50 percent of births in the East End were midwife delivered while in the prosperous West End and suburbs this figure was unlikely to rise above 5 percent (Loudon, Death in Childbirth, 176). Standards varied among midwives, and they were frequently depicted in negative terms, most famously Charles Dickens’ dissolute, incompetent and drunk Sairey Gamp. However, as Irvine Loudon has argued, for much of the nineteenth century the safest place to be delivered, regardless of social class, was at home by a well-trained midwife. Until the widespread use of antisepsis in the 1880s, male practitioners were more likely to carry infection, using unclean instruments and moving as they did between different types of medical cases and post-mortems to deliveries (Loudon, Death in Childbirth).

Childbirth was a costly event for poor families, who had to pay their birth attendant and provide necessities for the infant, though many local charities offered a modest layette for loan to families in need. Midwives remained popular in part because they were relatively cheap, charging a few shillings for attendance at a birth in poor areas, while a general practitioner cost around 10s 6d. Many local midwives or “handywomen,” despite having no formal training, also became very proficient, having worked alongside an experienced midwife and having attended many confinements. Working-class women might form strong links with traditional attendants; “They weren’t specialized people, only women that had a bent that way” (Beier 277). Flora Thomson in Lark Rise to Candleford described the local rural midwife, who, while not certified, “was a decent, intelligent old body, clean in her person and methods and very kind … She was no superior person coming into the house to strain its resources… but a neighbour … who would make do with what there was, or if not, knew where to send to borrow it” (135–6).

Mothers were expected to stay in bed for at least 10 days after the birth, during which time the midwife or a “nurse” assistant would take care of household chores and look after the other children. Childbirth for most women was very much a female-directed event. Husbands might be expected to fetch the midwife, but were rarely in attendance at deliveries, though Schneid Lewis found that aristocratic husbands were increasingly likely to be at the bedside or at least in close proximity by the 1830s (170–3).

Medical Men and Intervention in Childbirth

While anxieties around childbirth were certainly justified, as birth came under increased medical scrutiny and management during the Victorian period, these fears were heightened by medical men keen to establish themselves as obstetric practitioners and to ease out midwives, particularly from practice among wealthy families, which might command fees of several guineas. While the incursion of male midwives in childbirth had taken hold in the eighteenth century (Cody), during the Victorian period, more middle- and upper-class women employed accoucheurs and obstetricians, who by the end of the century were acquiring more specialised training. Though midwifery was considered time-consuming and unrewarding by some, surgeon-apothecaries (increasingly re-branded as general practitioners of medicine by the mid-nineteenth century), were often eager to expand their practices among well-to-do clients, with midwifery regarded as a reliable foothold in establishing a successful practice (Loudon, Medical Care, 94–9; Digby; see also "Advice to a Young Wife" by Anna Niiranen).

Surgeon's sign, England, 1750-1800. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

In their push to take over the work of delivering women from midwives, male practitioners increasingly framed childbirth as risky and normal only in retrospect, presenting themselves as experts not only in complicated or emergency deliveries but also as best qualified to attend at normal births. Coinciding with the emergence of the specialisms of obstetrics, gynaecology and psychiatry during the mid- to late nineteenth century, increased attention began to be paid to what came to be termed as “the diseases of women” (Digby). Medical textbooks spelt out the many potential complications and disasters associated with childbirth, often in graphic detail: tedious, complicated and instrumental labours, bleeding, fever, prolapse and disorders of the womb or breast. Professor of Midwifery Dr. Robert Lee offered little hope for women in his Lectures, published in 1844: “they are all exposed to great suffering and danger during pregnancy and childbearing, and many die from acute disorders following delivery” (Lee 1). Women of the upper classes accustomed to lives of leisure were described as weak and unfit to withstand the stress of maternity, requiring the support of a trained medical man who was able to use instruments, notably forceps, and after the mid-nineteenth century, obstetric anaesthesia, to ease delivery and reduce pain (Marland 22–26).

Obstetrical instrument set, 1851-1900. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Puerperal insanity (along with its sister disorders of insanity of pregnancy and lactational insanity) was one of the most striking examples of this framing of the risks of childbirth, defined as a severe mental disorder that commenced in the weeks following delivery, and which could equally afflict delicate upper-class women as well as poor women worn down by hardship and frequent pregnancies (Marland). By the mid-nineteenth century, it accounted for around 10 percent of admissions to many asylums, and prompted the distinguished psychiatrist, Dr. John Conolly, to explain how “Few cases can be supposed to occasion more distress in the family than the unexpected appearance of insanity in a young woman, just when she, her husband, her relatives, and her friends, are full of natural joy on account of her having safely become a mother” (Marland 35–8; Conolly 351).

Obstetric Anaesthesia

The nineteenth century was a period of technical innovation in midwifery, a process that tended to reinforce the position of male practitioners over midwives, who were not permitted to use obstetric instruments. Pioneered by Edinburgh obstetrician Sir James Young Simpson in 1847, chloroform began to replace ether and be used in midwifery cases as a form of pain relief. However, its take-up was limited by concerns about its safety, and the lewd and immoral behaviour it was said to induce among women during its administration, producing a state similar to inebriation or “occasional excitement of the sexual passion… a decidedly repulsive feature of anaesthesia” (Tyler Smith qtd. in Youngson 110).

Many doctors also insisted that the pains and sorrows of childbirth exerted a moral influence on women in labour, that pain was a necessary accompaniment of childbirth, and that the use of chloroform was an offence against God and Nature. However, following Queen Victoria’s decision to have chloroform administered by Dr. John Snow, at the birth of her eighth child, Prince Leopold, in 1853, which she described as “soothing, quieting and delightful beyond measure,” its use in childbirth became more widespread in both normal and difficult cases of childbirth (Woodham-Smith 328; Stephanie Snow).

Institutional Care and Midwife Training and Regulation

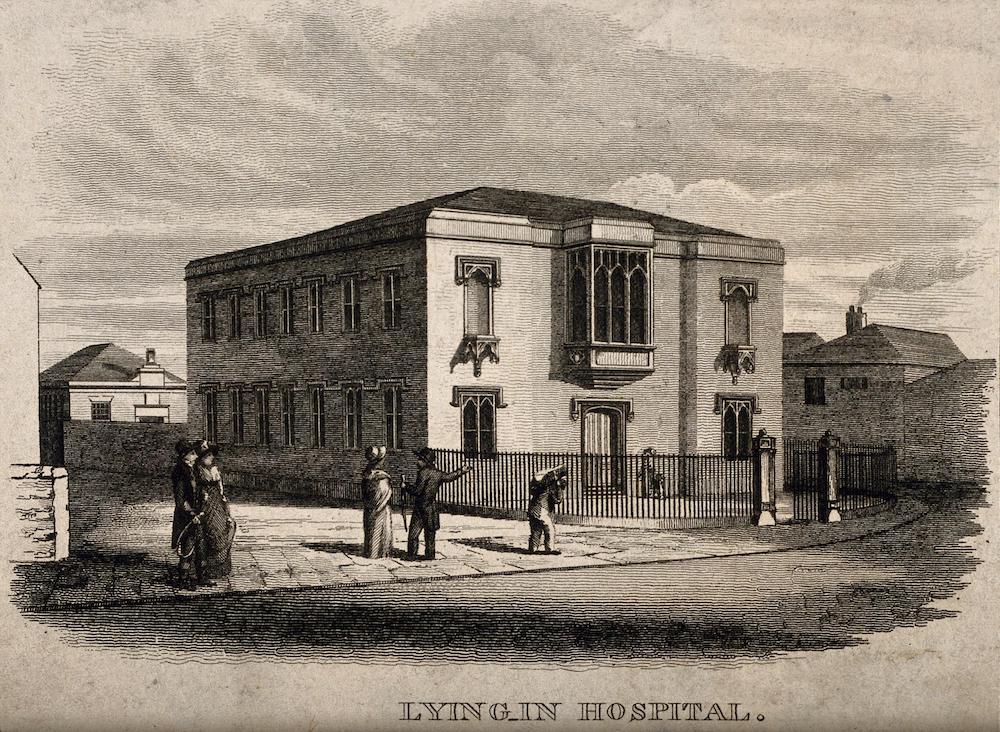

While the majority of poor women continued to be delivered by midwives at home, the very poor might give birth in hospitals or workhouse wards. Established in London and other major cities in the eighteenth century, lying-in hospitals offered outpatient and inpatient maternity care to women unable to pay for their deliveries. Women would normally be attended by midwives attached to the institution, while student midwives and medical students also undertook deliveries as part of their training. Though offering free and increasingly good standards of care to women, many women dreaded maternity hospitals as they were widely and accurately perceived as harbingers of infection and continued to experience regular waves of puerperal fever and excessive mortality rates among the mothers delivered there (Loudon, Death in Childbirth, 193–203).

Lying-in Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, opened 1826. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

The Poor Law also provided support to women in childbirth, paying for midwives and providing food and other necessities. However, after the introduction of the New Poor Law in 1834, confinements almost always took place in the workhouse rather than as a form of out-relief. Care varied greatly between workhouses, but in many conditions were grim. Philanthropist and workhouse reformer Louisa Twining described one workhouse lying-in ward “which was only a general ward without even screens, had an old inmate in it who we discovered to have an ulcerated leg and cancer of the breast; yet she did nearly everything for the women and babies, and often delivered them too” (Crowther 166). By the late nineteenth century, however, some of the larger and better run institutions set up well-run workhouse infirmaries and offered instruction to midwives. Alongside lying-in hospitals, a small number of women’s hospitals were established, which offered midwifery services for women in their own homes and at the same time provided training to midwives. Queen Charlotte’s Hospital in London offered midwives a three-month training after 1851, followed by an examination and the award of a diploma, while the Sheffield Hospital for Women opened in 1864, with domiciliary midwifery service for local women and paying trainee midwives during their training period (Donnison; McIntosh 405–6).

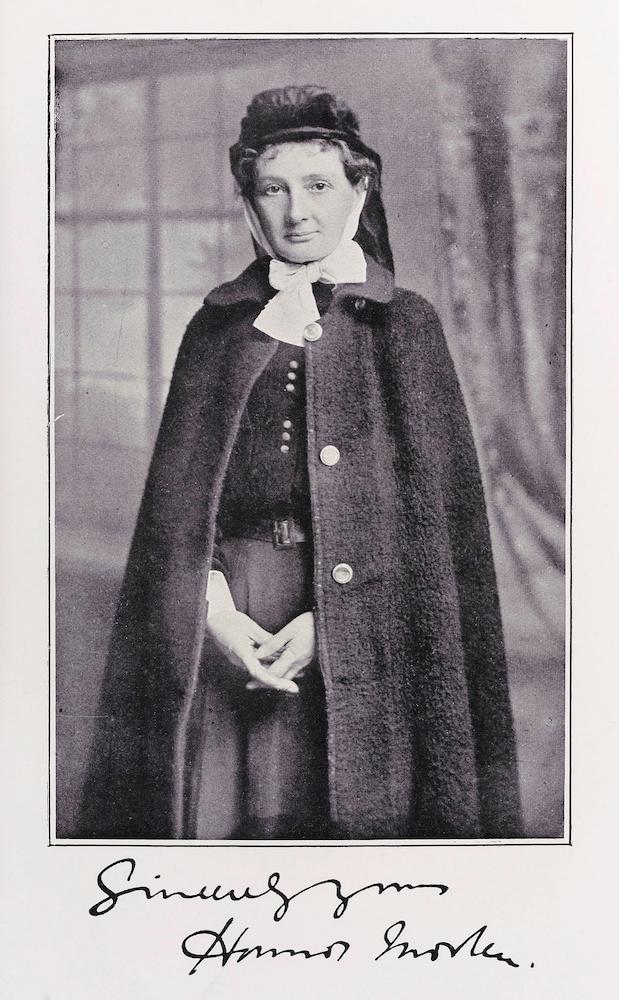

After the 1870s, midwives pushed for an extension in training and for professional recognition. The Midwives’ Institute was set up in 1881 with the aim of raising the efficiency and status of the midwife and to petition parliament for recognition. Its officers and many members were well-educated, middle-class women, who had close connections with the women’s movement and social welfare issues. Though lobbying for professional enhancement and recognition, they also advocated for improved services for poor women in childbirth (Hannam). In 1902 the Midwives Act instituted midwife registration and set up the Central Midwives Board, restricting practice to women who had a recognised qualification and could enrol on the register of midwives (Donnison). The cost of training and purchasing the required equipment was beyond the means of many traditional midwives, though in practice they continued to be employed by many women long after they were banned from working by law.

A Photograph of Honnor Morton in uniform, early twentieth century. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Conclusion

Though motherhood was idealized in the period, the reality of childbirth might well be less than ideal. For much of the Victorian period, childbirth remained dangerous for women and their infants, yet large families remained the norm. Deliveries were increasingly likely to be attended by a medical man, though midwives remained vital, especially for poor women and after 1902 midwives worked largely under the supervision of medical men. Though a small number of deliveries took place in maternity hospitals and, increasingly, in workhouse infirmaries, most babies—rich and poor—were born at home. Slowly, standards of care improved, and infant mortality began to fall towards the end of the nineteenth century; however, it was only in the 1930s that maternal mortality declined significantly, and attention slowly shifted from anxieties about harm to mothers and babies toward improving maternity services and experiences of childbirth.

Links to related material

Bibliography

Beier, Lucinda McCray. For their Own Good: The Transformation of English Working-Class Culture, 1880-1970. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2008.

Branca, Patricia. Silent Sisterhood. Middle-Class Women in the Victorian Home. London: Croom Helm, 1975.

Bull, Thomas. Hints to Mothers, for the Management of Health during the Period of Pregnancy and Lying-in Room. 16th ed. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1865, first pub. 1837.

Cody, Lisa Forman. Birthing the Nation. Sex, Science, and the Conception of Eighteenth-Century Britons. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Conolly, John. “Description and Treatment of Puerperal Insanity’, Lancet, 28 March 1846, pp. 349–54.

Crowther, M.A. The Workhouse System 1834-1929. London: Batsford, 1981.

Dickens, Charles. Martin Chuzzlewit. Serialised 1842–4. London: Chapman & Hall, 1844.

Digby, Anne. Making a Medical Living: Doctors and Patients in the English Market for Medicine, 1720-1911. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Donnison, Jean. Midwives and Medical Men: A History of Inter-Professional Rivalries and Women’s Rights. New York: Schocken, 1977.

Dwork, Deborah. War is Good for Babies & Other Young Children: A History of the Infant and Child Welfare Movement in England 1898-1918. London and New York: Tavistock, 1987.

Fulford, Roger (ed.). Dearest Child: Letters Between Queen Victoria and the Princess Royal 1858-1861. London: Evans, 1964.

Hannam, June. “Rosalind Paget: The Midwife, the Women’s Movement and Reform before 1914’, in Hilary Marland and Anne Marie Rafferty (eds). Midwives, Society and Childbirth. Debates and Controversies in the Modern Period. London and New York: Routledge, 1997, pp. 81–101.

Lee, Robert. Lectures on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1844.

Lewis, Jane. The Politics of Motherhood: Child and Maternal Welfare in England, 1900-1939. London: Croom Helm and Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1980.

Lewis, Judith Schneid, In the Family Way: Childbearing in the British Aristocracy, 1760-1860. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

Loudon, Irvine. Medical Care and the General Practitioner 1750-1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986.

_____. Death in Childbirth: An International Study of Maternal Care and Maternal Mortality 1800-1950. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

Marland, Hilary. Dangerous Motherhood: Insanity and Childbirth in Victorian Britain. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan: 2004.

McIntosh, Tania. “Professional, Skill, or Domestic Duty? Midwifery in Sheffield, 1881-1936,” Social History of Medicine, 11 (1998): 403–20.

Meigs, C.D. Females and their Diseases: A Series of Letters to his Class. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1848.

Moscucci, Ornella. The Science of Woman: Gynaecology and Gender in England 1800-1929. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Ross, Ellen. “Labour and Love: Rediscovering London’s Working-Class Mothers, 1870-1918,” in Jane Lewis (ed.), Labour and Love: Women’s Experience of Home and Family 1850-1940. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986, pp. 73–96.

_____. Love and Toil: Motherhood in Outcast London, 1870-1918. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Snow, Stephanie. Operations without Pain: The Practice and Science of Anaesthesia in Victorian Britain. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Thompson, Flora. Lark Rise to Candleford. Penguin ed. 1973, first pub. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

Woodham-Smith, Cecil. Queen Victoria: Her Life and Times, vol. 1, 1819-1861. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1972.

Youngson, A.J. The Scientific Revolution in Victorian Medicine. London: Croom Helm, 1979.

Created 23 September 2022