This article has been transcribed from a copy of the Cardiff Times in the online collection of scanned Welsh newspapers 1804-1919 in the National Library of Wales, with grateful recognition of the free access accorded to all readers. Paragraph breaks have been introduced for easier reading.

This is the liveliest of Samuel’s stories of sporting misadventure. It is probably intended to ride on the popularity of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat, the run-away success of the time, while capitalising on the popular songs ‘Row, brothers, row, and ‘The Jolly Young Waterman'. The captions to the second and third illustrations are taken from a popular song, ‘Two lovely black eyes.’ . Samuel, contrasts his incompetence with the deeds of mountaineers and of the French tightrope walker and acrobat, Charles Blondin (1824–97). (‘Deeds of derring-do’ is a frequent mistaken reference to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, which in fact means ‘daring to do those things which pertain to a knight’.) Bad puns abound, including those on three senses of ‘crab’ and on the two pronunciations of ‘row’. The Parnellite members were Members of Parliament elected on an Irish nationalist ticket, and considered particularly quarrelsome by the English public. The Leylands, which was ‘quite savage enough’ for Samuel, was a poverty-stricken part of central Leeds, where many Irish immigrants lived, alongside Jewish refugees from the pogroms of eastern Europe. There had been a significant outbreak of smallpox there in the previous year. Two illustrations are worth of remark: the second depending on what was then an embarrassing circumstance of two women rowing a boat with men as passengers, and the fourth, if viewed historically, representing the increase in cases of rickets among the urban poor. —David Skilton

Row, brothers, row.

I am reluctantly compelled, sir, to arrive at the conclusion that I am not a ‘plucky’ man; I am not a man who cares to do and dare much when my own personal safety is in question. I never stop runaway horses, as the heroes in novels do. I have no recollection whatever of making myself nasty and damp by jumping into a river and saving a fair damsel – or saving anybody else for that matter. I certainly never, whilst a huge crowd stood ‘spellbound’ (that is the orthodox penny-novelist word) with excitement and horror (a lathe newspaper reports and the ‘penny dreadfuls,’) rescued a whole family of children in their nightdresses from an eighth-story window just as the wild fierce flames were about to lick them with their (the flames') scalding tongues; I never defied ‘the devouring element’ – possibly if I had it would have devoured me; no subscription list was ever opened up on my behalf to reward my heroism, possibly because I never remember having displayed any of the latter, except once when I defied General Booth before some thousands of his regenerated chickens. No grey-headed father, with tears in his eyes, ever said, ‘Bless you, brave young man; you have restored to me mi own, mi daughter[!] [sic] Consider my colossal banking account yours[!]’ I don't even think that I was ever complimented on any occasion on my personal bravery. Even in my amusements, sir, I do not subject myself to hazardous undertakings. I never climb snow-clad mountains, there to hang on by my eyelashes, or to do Blondin feats on a ridge about as broad as the back of an ordinary table-knife; I never penetrate into savage countries amongst man-eating natives – the Leylands is quite savage enough for me; I never play at football; I never – but there, you quite understand, I never go in for deeds of ‘derring do.’

Considering now that this is the case, I cannot imagine why I recently went in for boating. I assuredly am not partial to water, except when the chill is taken off, and when I have entrusted myself to the element in question it has always been on a good safe boat, a sort of family Noah's Ark arrangement, and even then I have always been conscious of the fact that there was no back door to get out by. But my friend Thwarts has been for some time telling me in enthusiastic terms about the pleasures of sculling (ugh; the very name is suggestive of sudden death and tombstones) the mad delight of shooting along in a canoe (canoes always did look like coffins to me), and the inspiriting influence of a row in a single-oared outrigger – a species of boat which always looks to me just a little less safe than an ordinary plank, propelled and steered by means of a clothes prop. Thwarts, in order to rouse me to his own elevation of enthusiasm, sang for me ‘Row, brothers, row', a song which always reminds me, when the pronunciation of the word ‘row’ is slightly altered, of the Parnellite members, and I ultimately agreed, ass that I was, to make one of a boating party on a lake at a Park not many miles from home.

‘Oh, what surprise.’

There were about six in the party in question, some of them being ladies, and all of them were attired in the most correct boating costumes. You will generally notice, sir, that complete novices at any given sport always make a point of mounting all the outward evidences of their participation in the sport in question. Thus it was, sir, that a most liberal display of white flannels and straw hats with many-coloured bands round them was to be observed amongst the party. It was not till we began to approach the lake that I began to feel somewhat uncomfortable, sir. though I affected to be facetious enough all the time. ‘Let's take a tub,’ quoth I, and then I tried it on with a quip, sir, about ‘tub-be or not tub-be,’ but it fell flat, although I followed it up by saying that the only sort of vessel I didn't care for was a ‘smack,’ although I had frequently had one in my eye. I also playfully remarked that I generally liked a couple of ‘skulls,’ inasmuch as two heads were always better than one – but I felt desperately uneasy, sir, all the same, when I surveyed the boats which were displayed to us.

Thwarts wanted to take a long narrow thing that actually wobbled about when a fly settled on it, but I protested that for myself I liked a substantial boat in which I could stretch my legs – a boat with which it was possible for a man to cough or sneeze without capsizing the whole concern, and I recommended a fine, broad beamed, Aire and Calder Navigation warranted- to-carry-twenty-tons sort of a craft. Thwarts and the rest actually turned mean and spiteful at this suggestion, and someone said I looked ‘upset’ but I retorted, sir, by saying that I didn't feel ‘upset’ then, but I was afraid that I very soon should do. nd when we ultimately procured a sort of compromise between the two vessels in question, and I recommended that we should take a boatman with us, an objectionable friend of Thwarts, who evidently thought that he was a funny man, asked me why I hadn't brought my nurse out with me. He also inquired of me whether I had brought a piece of soap, so that I might ‘wash myself ashore’ in case of accident. Then we all embarked. Good gracious, bow that miserable boat did wobble about. I got my right leg on one side of it, and was just about to step in, when the fragile uneasy thing seemed to shoot out into the lake, and my left leg went into the water. If I hadn't held on to Thwarts' wife, who weighs a good lot, I should probably have been the subject of a coroner's inquest. I got into the boat at last though, sir, and there I sat shivering, and not daring to move an inch, with my knees up to my chin, and when Mrs Thwarts came flopping into her place astern, I thought it was all over with the lot of us.

‘Of course, you'll pull,’ said Thwarts, and I said, in a voice which I am afraid shook somewhat, no doubt through the tremulous motion of the boat and my previous immersion, ‘Oh, certainly.’ I seized an oar, sir, and as I did so I felt like a veritable galley slave. ‘Give way,’ shouted Thwarts, and 'pon my word I never in my life felt more like ‘giving way’ and pleading such indispositions as would oblige me to be put ashore. ‘But I'm in for it now,’ I said to myself at the same time remembering that I hadn’t paid up my last insurance premium. ‘Give way,’ was again shouted, so I dipped my oar in the waters of the lake and attempted to pull. I skimmed my oar on the surface of the lake merely, it appears, for I threw up a perfect shower of water, and, I am happy to say, nearly deluged Thwarts’ friend. ‘Put it in deeper’ shouted Thwarts, so I did, and then I felt as though some sub-aqueous (is that the right word?) monster had seized the oar in his grip, for to get it through the water, I couldn't, and with the recoil I turned a fearful backward somersault right into the lap of Thwarts' funny friend. Oh, how that boat did roll from side to side. I felt dreadfully foolish, sir, as well as alarmed, for the ladies began to laugh, and a low-looking man with a terrier dog on the bank, shouted out, ‘Nail him down, or he'll be catching another crab.’ I was ‘that crabby’ that he would have caught a considerable crab had I been ashore. As for Thwarts' friend, he very bitterly remarked that had he known he was coming for a row with a man who couldn't ply an oar, he I would have stopped ashore. As I didn't know I what ‘plying’ meant I didn't trouble about re-plying, but endeavouring to get my oar, which had fallen over into the water and was slowly drifting away, I made a grab at the oar, sir, and nearly upset the boat and the ladies screamed, and the man on the bank told a boatman to get the ‘drags’ ready, as there would be another ‘do’ for ‘Malcolm, t' coroner,’ in a day or two. I lost my hat in the wild struggle, sir, and it floated triumphant in the lake. I had already ‘lost my head,’ so the hat wasn't so much misled.

Amused spectators.

But I tried again, sir, and despite the fearful blistering of my hands; despite the awful exertion of the unaccustomed strain on my muscles (a strain which simply inundated me with perspiration); despite the buzzing of a loathsome insect near my nasal organ; despite the jeers of my comrades; despite still one more upset; despite the fact that the oar would persistently work its way out of the rowlocks; despite the involuntary showers which I sent up for the benefit of my fellow-creatures in the boat; despite all these things I got on fairly well. But my sufferings were awful. And the fiendish Thwarts began to sing ‘The Jolly Young Waterman'. ‘Jolly, indeed,’ did I mentally and very bitterly say to myself, but I persevered and perspired. At length, seeing that all my frantic exertions did not suffice to keep me in time with the other oarsmen (as a consequence of which the boat progressed in a devious and serpentine course), it was decided that one of the ladies should take an oar (oh, lamentable degradation that I should be obliged to give in to a young female person) whilst I took upon myself the duties of steersman.

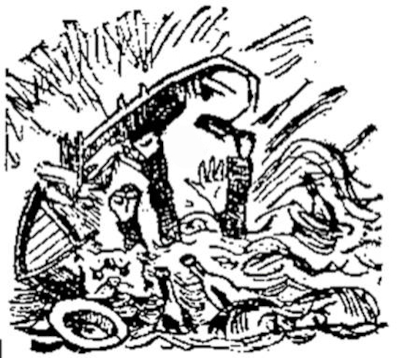

Then came the awkward incident of a change of places between the young lady and myself. Very cautiously did I step towards the stern gearing, and should have got on all right had I not caught my foot against one of the thwarts, as a consequence of which I shot forward. In my fearful desperation I clutched at the young lady and nearly pushed her overboard. And there was more screaming, and that amiable woman, Mrs Thwarts, said that I evidently wished to murder the whole party. And I got on worse with the steering than I did with the pulling, for I was unnerved, sir, and when I was asked to pull to the right, I turned the boat to the other side, and vice versa. And worse than that, sir – I steered the boat into another one, laden with a large family party – and a cargo of ‘pop’ and stale buns. A fearful yell ascended to the blue heavens above, and a child fell overboard from the other boat. Luckily, it was fished out by its ‘Pa,’ a hulking fellow, who challenged me to single combat on the bank, and after I had succeeded in directing the whole of my own party in a very circuitous way to the landing place, I bid good-bye for ever to Thwarts, his relations, and friends, and boating. I hate boating, sir. Even a ‘cockle’ boat requires too much mussle – muscle, I should say — to propel it, and a ‘dingy’ is, to me, even more black than it is painted. Frightful have been my dreams, sir, since that day's boating – but the picture above will about realise for you the sort of scenes which I have in imagination passed through during the long and silent watches of the night.

Last modified 3 March 2022