To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. "On Holiday with James Tissot and Kathleen Newton, by Lucy Paquette for The Victorian Web." Victorian Web. < Complete url >. Web. Date viewed. [Formatting by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on all the images to enlarge them, and for more details where available.]

ames Tissot and Kathleen Newton lived in relative seclusion during their years together in London, from about 1876 until her death from tuberculosis in late 1882, but they enjoyed numerous trips outside the city in 1878.

Partly, as an unmarried couple living together, they were not welcome in respectable company. Kathleen's two children lived nearby with her sister, Polly, who brought them to visit at tea time. But Tissot spent a great deal of time painting at his home, and Kathleen was his primary model during these years. Still, they managed what essentially were working holidays, when he painted her while they enjoyed excursions to resort towns easily accessible from his villa in suburban St. John's Wood, London. Each of their destinations had its own attractions, described in contemporary travel guides.

Greenwich

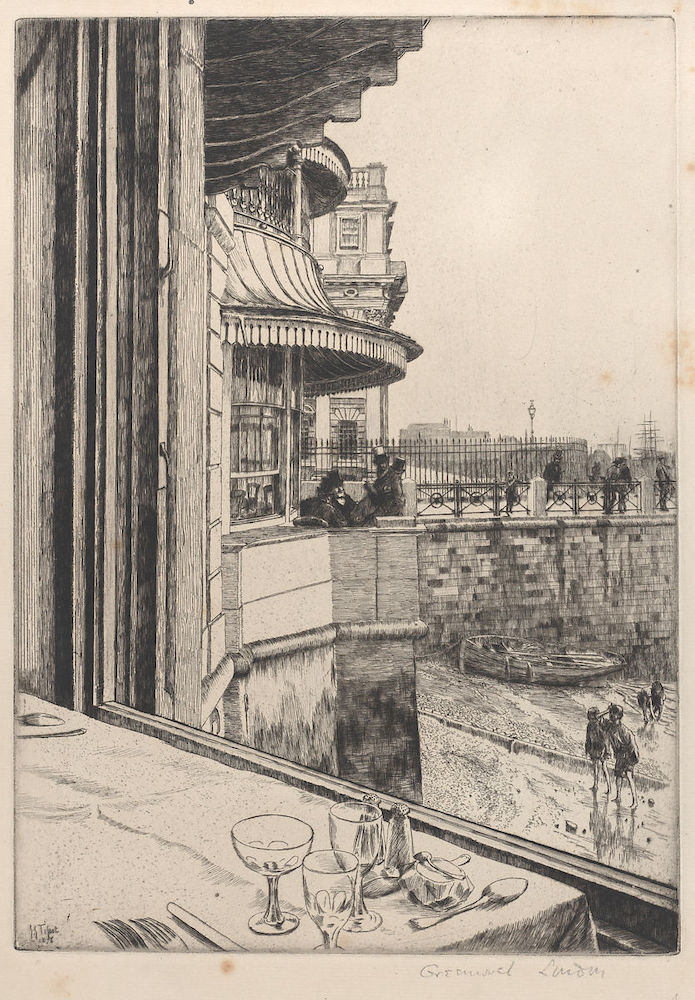

Tissot's The Terrace of the Trafalgar Tavern, Greenwich, London Greenwich, London (c. 1878).

In Greenwich, Tissot painted The Terrace of the Trafalgar Tavern, Greenwich, London Greenwich, London (c. 1878). On the south bank of the Thames, Greenwich was four miles from London by road and railway, and five or six miles by river from London Bridge. The parish of Greenwich had a population of 40,412 in 1871, and the town was an important manufacturing center, with engineering establishments, steel and iron works, iron steamboat yards, artificial stone and cement works, rope yards, a flax mill, and a brewery. The meandering streets, less than picturesque at that time, held a market, a theatre, a literary institute, a lecture hall, public baths, banks, and twenty almshouses.

J. M. W. Turner's London from Greenwich Park (1809).

The glory of the town was Greenwich Hospital, a home for retired Royal Navy sailors until 1869, which commanded the view from the Thames. Designed by Sir Christopher Wren, its Painted Hall contained a picture gallery that was free to the public on Monday and Friday, and four pence on other days.

Trafalgar Tavern, Greenwich, 1878.

Behind the Hospital, visitors could enjoy the beautiful 190 acres of Greenwich Park, and the view of Royal Observatory above it. The park, designed on plans by King Louis XIV's landscape architect, André Le Nôtre by commission of Charles II, had been magnificently terraced and planted with avenues of elms in 1664. It was now in a state of neglect but still had charming, distant views of London and the Thames for the crowds who came to enjoy the open air and the deer fearless enough to feed from visitors' hands. On its summit was the Royal Observatory, founded by George III, and while this was not open to the public, there was an electric time-ball that fell every day at precisely 1 p.m., an electric clock, a standard barometer, and highly accurate standard measures of length for public use by the entrance gates.

The Trafalgar Tavern was one of four riverside inns operating at that time; all were known for their whitebait dinners – for diners with the means to enjoy them. The Terrace of Trafalgar Tavern is inscribed "No. 1 Trafalgar Tavern/(Greenwich)/oil painting/James Tissot/17 Grove End Road/St John's Wood/London/N.W." on an old label on the reverse.

Gravesend

Two versions by Tissot of Waiting for the Ferry (c. 1878), both in private collections.

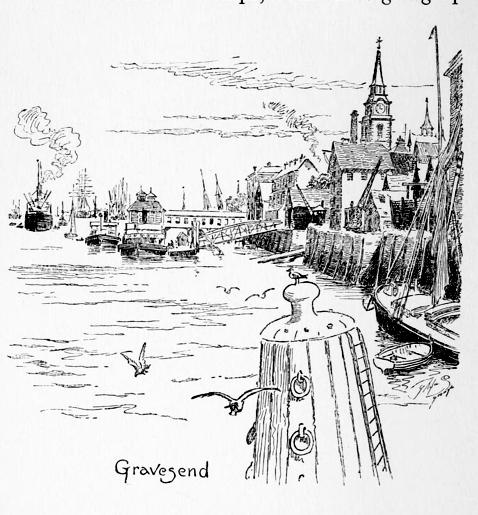

In 1878, the couple traveled a bit farther, to Gravesend, the setting for two versions of Waiting for the Ferry (1878). Gravesend was accessible by numerous river steamers which conveyed crowds of passengers during the day, as well as by trains on the Tilbury Railway and the North Kent Railway; a steam-ferry transported visitors from Tilbury over to Gravesend. The trip was about 27 miles by river, or 24 miles by rail. By 1878, Gravesend had a population of 22,000, and the influx of summer visitors brought unexpected prosperity.

At that time, Gravesend fishermen hauled in shrimp in prodigious quantities, mainly for the London market, but the streets of Gravesend teemed with "tea and shrimp houses." The formerly crowded, labyrinthine medieval old town boasted new and wider streets, and a new town with broad streets was lined with shops, homes, and lodging-houses.

Gravesend, in a drawing by G. Ayton Symington. Source: Father Thames

While the churches and public buildings of Gravesend were of little interest to tourists, with the exception of the impressive Town Hall and the massive, "Collegiate Gothic" College for Daughters of Congregational Ministers, Milton Mount (built in 1872-73), there was a theatre, and the Assembly Rooms in Harmer Street, built in 1842 as a Literary Institute, featured a concert-room for one thousand persons, as well as billiard-rooms. The Town Hall, near the center of High Street, was built in 1836 on the site of previous town halls, and was fronted by colossal Doric columns over which a pediment featured the town arms and statues of Minerva, Justice, and Truth. Beneath the Great Hall on the main floor was the market: A corn market was held in the town on Wednesdays, a general market on Saturdays, and a cattle market monthly. Along the river, there were barge and boat building yards, iron foundries, rope walks, breweries, steam flour mills, soap and other factories. Beyond those were market gardens, renowned for asparagus and rhubarb, and cherry and apple orchards.

For visitors, the place to be was the Town Pier, with its 40-foot cast-iron arches extending 127 feet into the river. It was the landing for the London steamers and the location of the railway ticket office. Built in 1832, the Pier was covered in 1854 and featured sliding shutters on the sides, making it possible in any weather to stroll along the river. On summer days, a band played, and there were occasional balls. The favorite hotels, such as the Clarendon and the Roebuck, were located near the Pier. Bathing machines were within walking distance, and since Gravesend was the headquarters of the Royal Thames Yacht Club, watermen kept busy conveying passengers to and from the vessels anchored off the Club House on the Main Parade. All in all, Gravesend offered plenty of entertainment to fill James Tissot's and Kathleen Newton's leisure hours.

Tissot painted three versions of Waiting for the Ferry, one in 1874 (Speed Museum, Kentucky), and two around 1878, at the dock beside the Old Falcon Tavern, Gravesend; Kathleen Newton modeled for the figures in only the latter two versions. She wears the same triple-caped greatcoat that Tissot portrayed her wearing in numerous other paintings, including The Terrace of the Trafalgar Tavern, Greenwich, London.

Photograph c.1878: Kathleen Newton (center) and James Tissot (right) with her son, Cecil Newton. Source: Wikimedia, described as being in the public domain.

While this third version of Waiting for the Ferry is said to have been painted around 1878, Kathleen Newton's son, Cecil, was born in March, 1876, and he clearly is older than two or two and a half here. In fact, it must have been painted in 1882, when Tissot painted Cecil at about six in The Garden Bench, wearing the same knit cap and brown suit. That would make the young girl in this Waiting for the Ferry Lilian Hervey, Kathleen Newton's niece, who was seven in 1882 [Kathleen's daughter, Muriel Violet Newton, was born in December, 1871 and would have been about ten at this time, too old to be the girl shown in this version].

Tissot, Kathleen Newton, Cecil Newton, and Lilian Hervey posed for a photograph that gives some insight into how the artist composed this later version of Waiting for the Ferry, simply painting in the background from the previous version.

Ramsgate

Ramsgate, West Cliff, a watercolour by an unidentified nineteenth-century British artist.

The farthest the couple ventured on these excursions was Ramsgate, a seaside resort on the Kent coast, seventy-eight miles southeast of central London. There, Tissot painted Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait, 1878) and Room Overlooking the Harbour (c. 1878-79).

Londoners could take the train from Victoria Station to Ramsgate on the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway. A travel guide of the time highly recommended this resort, population 12,000: "It is impossible to speak too favourably of this first-rate town, its glorious sands, its bathing, its hotels, libraries, churches, etc. etc. not forgetting its bracing climate."

Ramsgate by Tissot, pen and ink.

The streets of Ramsgate are well paved or macadamized, and brilliantly lighted with gas. There are banking establishments and a savings bank, with a literary institute, assembly-rooms, a small theatre, several good libraries, dispensary, town-hall, custom-house, music-hall, gas-works, water-works &c. An excellent promenade on the West Cliff has been laid out in an ornamental manner, and forms a delightful source of healthy recreation. The bathing-machines are under the East Cliff, where also, as well as in front of the harbor, there are well-appointed warm baths, &c. The markets are extremely well supplied with meat, excellent fish, &c.; and few places on the coast are so cheap, as well as healthy and agreeable for a summer's residence.

Vincent Van Gogh moved to Ramsgate in April, 1876, at age 23, to work as an assistant teacher in a boys' school for a brief time. He wrote to his brother Theo, "There's a harbour full of all kinds of ships, closed in by stone jetties running into the sea on which one can walk. And further out one sees the sea in its natural state, and that's beautiful."

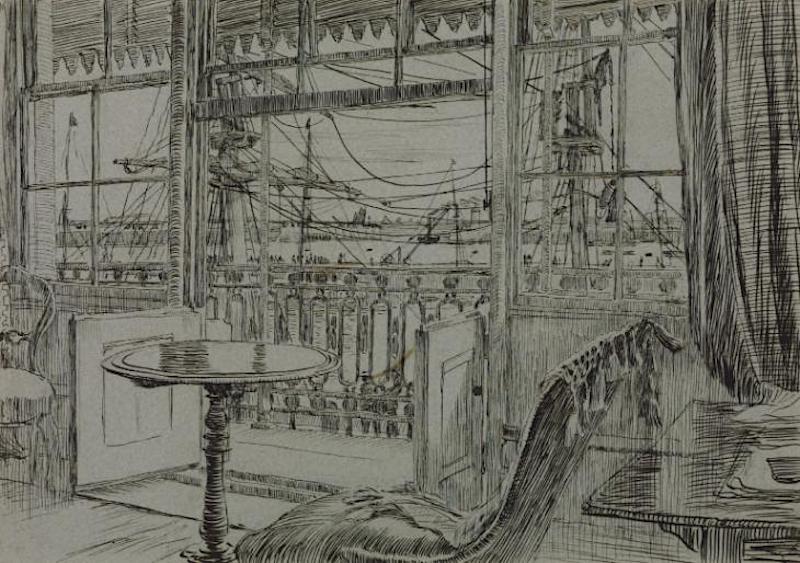

Right: Tissot's Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait), 1878. Left: Room Overlooking the Harbour (c. 1878-79).

The setting for Seaside was the Royal Albion Hotel near the shore of Viking Bay in Ramsgate, Built in 1791, Albion House sits atop the East cliff, with a sweeping view of the beach and the Royal Harbour. Princess Victoria stayed in one of its elegant rooms, ornamented with Georgian and Regency cornices, iron balconies, and shutter-panelled windows, before she was crowned Queen.

Kathleen wears one of the prop gowns Tissot often used, a summery white gown trimmed with lemon-yellow satin ribbons that featured in a half-dozen of his oils in the mid-1870s, including A Portrait (1876, Tate Britain), A Convalescent (c. 1876, Museums Sheffield), A Passing Storm (c. 1876, Beaverbrook Art Gallery, New Brunswick), and Spring (c. 1878, private collection).

Tissot exhibited Seaside, along with nine other paintings, at London's Grosvenor Gallery – a sumptuous, invitation-only showcase for contemporary art in New Bond Street – in 1878, the year it was painted.

He made a copy (now in a private collection), showing Kathleen Newton wearing a tight blonde bun. He gave this version to Emile Simon, administrator of the Théâtre l'Ambigu-Comique at 2, Boulevard Saint Martin, Paris from 1882 to 1884. Simon sold it as La Réverie in 1905; this version of Seaside, (also known as July), La Réverie, and Ramsgate Harbour) is signed and inscribed: "J.J. Tissot a l'am(i) E. Simon en bon Souvenir" (on the horizontal bar of the window frame). At some point, another artist painted a frizzy red hairstyle (probably considered more up-to-date) on Kathleen Newton.

In Room Overlooking the Harbour (c. 1878-79), Tissot depicts Kathleen Newton going about her business while an older man (who could be a servant accompanying the couple) gamely models as well. The picture has been held by the same family since 1933. In excellent condition, though needing to be cleaned and re-varnished, it was sold at Sotheby's, London on July 11 2019, for £400,000 (Hammer price).

Richmond

Turner's watercolour of Richmond Bridge in 1837.

In 1878-79, the couple traveled west to Richmond, a village on the south bank of the Thames, where Tissot painted By the Thames at Richmond (oil on canvas) and Richmond Bridge (oil on panel, 35.6 x 22.9 cm).

Richmond, about nine miles by land from central London, was easily accessible by omnibuses running frequently from the City and West End. The trip was 16 miles by river, but because the Thames was too shallow there for steamers, the trip was usually made by railway – from the Waterloo, Vauxhall, and other stations. The District Railway connected Richmond to the London Underground in 1877, making the trip from Tissot's villa near the Swiss Cottage Underground station (opened in 1868) possible. Richmond Bridge, built of Portland stone between 1774 and 1777, began as a toll bridge, but tolls ended in 1859. Its five segmental arches, rise gradually to the tall, 60-foot wide central span which allowed vessels to pass through the tallest arch.

By the Thames at Richmond. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In Richmond Bridge, Kathleen Newton wears the green tartan gown from Room Overlooking the Harbour and The Warrior's Daughter (The Convalescent, c. 1878, Manchester Art Gallery, U.K.). In By the Thames at Richmond, she wears the striking, simple brown floral dress also worn in three oil versions (and one watercolor version) of La sœur aînée (The Elder Sister, c. 1881) and in The Garden Bench (c. 1882, private collection). The little girl is in the exact same pose and outfit as in the photograph above, painted in the third version of Waiting for the Ferry. The man uses his cane to trace "I love you" in the ground beneath the woman's gaze.

Kathleen Newton, who died of tuberculosis in 1882, was depicted in a chaise-longue looking ill by Tissot in The Dreamer (Summer Evening, Musée d'Orsay ), c. 1876. While the secluded couple's trips outside the city in 1878-79 must have been liberating escapes made possible by new forms of transportation, they also may have been just what the doctor ordered.

Related Material

- The Development of Leisure in Britain after 1850

- The Seaside in the Victorian Literary Imagination

- Technology and Leisure in Britain after 1850

- The Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich, and its Environs: Their Victorian Interest

Bibliography

Baedeker, Karl. London and its environs, including excursions to Brighton, the Isle of Wight, etc.: handbook for travelers. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1878.

Collins' Illustrated Guide to London and Neighbourhood. London: William Collins, Sons, and Company, 1875.

Matyjaszkiewicz, Krystyna, ed. James Tissot. New York: Abbeville Press, 1985; Barbican Art Gallery, c. 1984.

Measom, George S. Official illustrated guide to the South-Eastern railway, and its branches. London: Reed and Pardon, c. 1860.

Misfeldt, Willard. "James Jacques Joseph Tissot: A Bio-Critical Study." Ph.D. diss., Washington University. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms International, 1971.

Misfeldt, Willard E. J.J. Tissot: Prints from the Gotlieb Collection. Alexandria, Virginia: Art Services International, 1991.

Paquette, Lucy. "Artistic intimates: Tissot's patrons among his friends & colleagues." The Hammock. Web. 8 July 2019.

Paquette, Lucy. "The Artist's Closet: James Tissot's Prop Costumes." The Hammock. Web. 8 July 2019.

Paquette, Lucy. "The Art of Waiting, by James Tissot." The Hammock. Web. 8 July 2019.

Sotheby's. "Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite and British Impressionist Art, 11 July 2019." Lot 36, Condition Report. Web. 11 July 2019.

Thorne James. Handbook to the Environs of London, Part I. London: John Murray, 1876.

Wentworth, Michael. James Tissot. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984.

Wood, Christopher. Tissot: The Life and Work of Jacques Joseph Tissot, 1836-1902. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd., 1986.

Created 15 July 2019