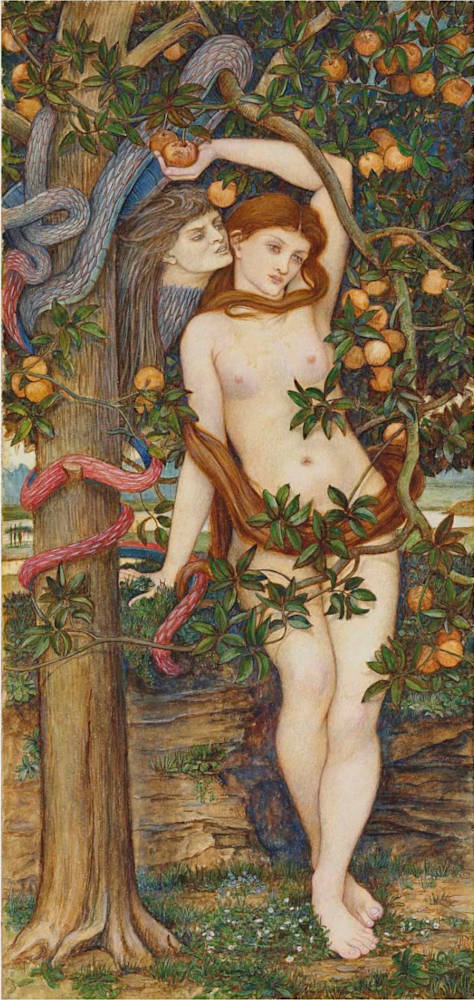

Left: Eve Tempted. Tempera on panel, 637/16 x 293/4 inches (161.2 x 75.5 cm). Collection of Manchester Art Gallery, accession no. 1883.29. Right: Eve Tempted. Watercolour and gouache on paper, 221/2 x 103/4 inches (57 x 27 cm). Private collection. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

his work exists in several versions, the principal of which is now in the collection of the Manchester Art Gallery. Another large example sold at Sotheby’s, New York, on June 9, 1994, watercolour and gouache heighted with gold, 591/4 x 291/4 inches (150.5 x 74.5 cm). The subject of these pictures is a somewhat unnerving, yet striking, depiction of the temptation of Eve taken from Chapter III of the book of Genesis. The naked figure of Eve stands beneath the Tree of Knowledge on a carpet of grass with blue, white and yellow flowers. This is similar to foregrounds portrayed in early Florentine Renaissance paintings. Her right hand leans against the earthen bank behind her while her left hand reaches up over her head to grasp an apple. Eve faces forward, her eyes blankly gazing downwards, and her left leg lies in front of her right. Her long hair, blonde or red depending on the version, hangs behind her and then swoops up at her right hip to cover her genital area.

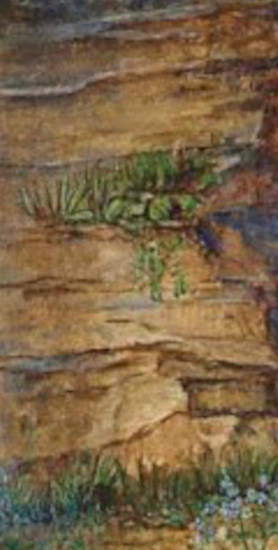

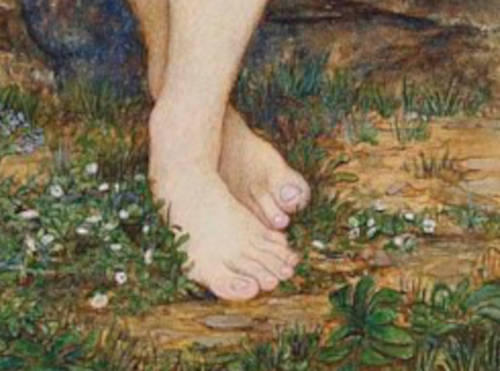

Three details from the watercolour and gouache version [Click on images to enlarge them.]

A blue-grey serpent, with a hideous human head, is entwined about the trunk and branches of the Tree of Knowledge whispering temptation into Eve's ear. The setting differs in the various versions, including the Tree of Knowledge and the earthen or rocky bank Eve rests against, but was probably based on the garden of Stanhope’s Villa Nuti on Bellosguardo. The model for Eve has again been suggested to be Maria Zambaco. As Poë has pointed out she was “recognisable by her sturdy legs, big handsome feet and small bosom…For an upper-class, non-professional model to pose nude in the Victorian period was not merely unusual – it was unheard of. However, Maria was an extraordinary woman” (80-81). She had previously posed nude for Edward Burne-Jones’s Venus Epithalamia of 1871.

In 1877 the Grosvenor Gallery had its inaugural exhibition and soon found itself the most important venue for the painters associated with the Aesthetic Movement, particularly Edward Burne-Jones and his followers. F. G. Stephens writing in The Athenaeum commented about these artists:

On the other side of Mr. Jones’s compartment will be found another symptom of delight in the old North Italian school; it is Umbrian in defect of colour, Venetian in luxury of sentiment, Florentine in the imperfectly expressed sense of grace, the elaborate draughtsmanship and romantic inspiration…This lack of independence is traceable in all these painters, even in a degree in Mr. Jones; but to Messrs. Stanhope and Crane especially. The style of thought and painting which is affected by these extremely able and cultivated men is nowadays at least the result of culture, over-refinement, and caprice. Mr. Rossetti has quite outgrown whims of this sort and carried his practice to its legitimate conclusion, not stopping with the early fifteenth century, but growing with the following period, and painting as Titian and Giorgione painted, designing like himself, with all his might and main. The style affected by our neo-Italians, Umbrians, Florentines, Mantegnesques, Venetians, and what not, is, it must be admitted, marked by what may be called an arrest of development” (584).

When the principal version of this work was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877, along with three other works, it was considered one of his major contributions. The Art Journal commented ”We must likewise commend Spencer Stanhope’s ‘Eve Tempted’ (53)” (244).

One of the best reviews of this picture came from the young Oscar Wilde while still an undergraduate at Magdalen College, Oxford, who considered it one of the principal paintings in the exhibition:

Mr. Spencer Stanhope’s picture of Eve Tempted is one of the remarkable pictures of the Gallery. Eve, a fair woman, of surpassing loveliness, is leaning against a bank of violets underneath the apple-tree; naked, except for the rich thick folds of gilded hair which seep down from her head like the bright rain in which Zeus came to Danaë. The head is drooped a little forward as a flower droops when the dew has fallen heavily, and her eyes are dimmed with the haze that comes in moments of doubtful thought. One arm falls idly by her side, the other is raised high over her head among the branches, her delicate fingers just meeting round one of the burnished apples that glow amidst the leaves like ‘golden lamps in a green night.’ An amethyst-coloured serpent, with a devilish human head, is twisting round the trunk of the tree and breathes into the woman’s ear a blue flame of evil counsel. At the feet of Eve bright flowers are growing, tulips, narcissi, lilies, and anemones, all painted with a loving patience that reminds us of the older Florentine masters; after whose example, too, Mr. Stanhope has used gilding for Eve’s hair and for the bright fruits. [121]

Bibliography

Poë, Simon: “Roddy, Maria, and Ned (And Georgie, Topsy, Janey, and Gabriel): An Entanglement.” The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies New Series 9 (Fall 2000) 69-87.

“The Grosvenor Gallery.” The Art Journal New Series (1877): 244.

Stephens, Frederic George. “The Grosvenor Gallery Exhibition.” The Athenaeum No. 2584 (May 5, 1877): 583-84.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Grosvenor Gallery.” The Dublin University Magazine 90 (July 1877): 118-26.

Last modified 7 May 2022