Note that the illustrations here (after the first one, of the front cover) come from our own website rather than the book itself, which, however, is very generously illustrated. — JB.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, according to the proverbial saying, bringing together many pictures should be worth many thousands. This multiplicative rule is verified in the gorgeous volume which Editions Cohen&Cohen have recently devoted to John Singer Sargent. Curiously enough, this is apparently the very first book in French devoted to the whole career of the American painter: indeed, when the exhibition of Sargent's work co-organised with the Metropolitan Museum of Art came to the Musée d’Orsay last autumn, the artist was “discovered” by an important part of the French public — who may have already forgotten that a selection of his works had been displayed with those of Spanish painter Joaquin Sorolla some twenty years before at the Petit Palais in Paris. The centenary of the death of Sargent was deemed an ideal if belated opportunity to publish a monograph in a language which the artist himself mastered, as he spent about a decade in the French capital between 1874 and 1884.

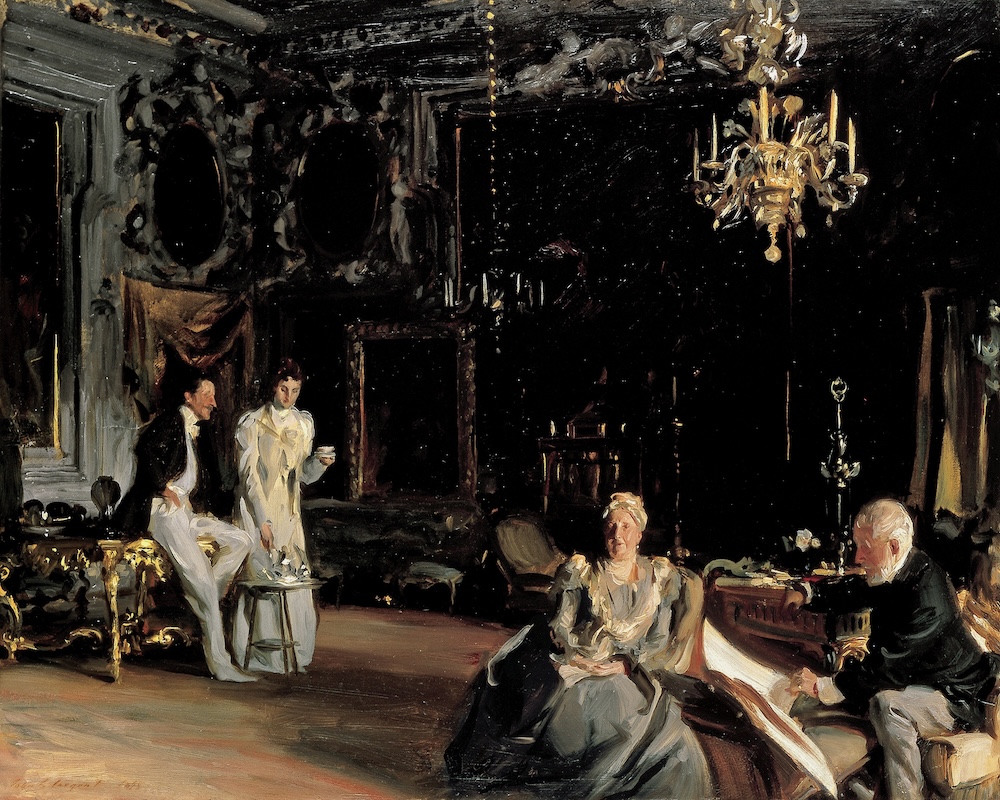

As mentioned above, the first striking characteristic of the Cohen&Cohen volume is its wealth of illustration. Only two reproductions out of 350 are split by the binding seam, the magnificent An Interior in Venice on pp. 68-69 and J.M.W. Turner’s 1805 Shipwreck on pp. 292-93. Why those two, might one ask, if even the very horizontal El Jaleo could be printed on one page? That arrangement meant that most of those full-page reproductions could be juxtaposed with other works, by Sargent himself or by other artists, either Old Masters – Velazquez, Van Dyck, Reynolds, Gainsborough… – or his contemporaries, like Carolus-Duran, his teacher, Monet, Whistler, Blanche and so on. Albert Moore, however, is missing, though he might usefully have been summoned in relation to Sargent’s fondness for sleeping models, the use of the archaic French word “nonchaloir” as a title showing that the American may have been familiar with Mallarmé’s poetry. The comparison speaks for itself, generally, and in the rare cases when it might seem almost irrelevant (Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters and Sargent’s Tyrolese Interior, for instance), the authors themselves underline that the similarity is merely superficial: bringing William Holman Hunt’s The Scapegoat side by side with Sargent’s watercolour of the Hills of Galilee just because they share a purple background might raise an eyebrow, if one did not read this pre-emptive comment on p. 336: “But there is a world of difference between this partly mystical vision, inspired by the Old Testament, and Sargent's, which is devoid of any metaphorical meaning.”

"...the magnificent An Interior in Venice." [Click on the image for more information.]

The material proximity between two pictures also allows the authors to sustain their claim that Sargent was a multifaceted painter, who did more than paint swagger portraits for wealthy commissioners. The subtitle of the book, Le beau monde et son revers, plays on a French phrase which means “high society” as well as “beautiful people,” in opposition to the “other side of the coin,” the Spanish and Venetian poor being like the reverse of the British and American nouveaux riches. The text is divided into six chapters which focus on various aspects of Sargent’s career, like his interest in other forms of art, dance in particular, or his more or less exotic landscapes. His work for the Boston Public Library might have been more generously documented, and one wonders why the frescoes of his colleagues Edwin Austin Abbey and Puvis de Chavannes are reproduced in black and white (pp. 384-85; one suspects the reproduction fees may have been somewhat higher than expected, which would also explain why G.F. Watts’s portrait of Mrs Percy Wyndham, which Sargent ”quoted” in his group portrait of her daughters, is only present through a sketch rather than the finished version, on p. 125). A few more colour illustrations from Boston would have been all the more appreciated, since this is a segment of Sargent’s work that can only be admired in situ.

Left: G.F. Watts's sketch of Madeline Wyndham, née Campbell (1835–1920) (1867-71). Right: Sargent's The Wyndham Sisters: Lady Elcho, Mrs. Adeane, and Mrs. Tennant (1889). [Click on the images for more information.]

Another point is not quite clarified in the book: in spite of vaguely tantalizing allusions to the artist’s “sexual orientation” about which he constantly tried to “obscure the truth” (pp. 26 and 202), the authors eventually have to concede that nothing is known about Sargent’s private life. He left no private archives which might shed light on his affairs, if any; the fact that he wrote down the address of a male model on a sketch, mentioned on p. 213, was simply common practice among painters at the time, as it made it easier to get back in touch for strictly professional purposes.

It is nevertheless to be noted that Sargent is here assessed by three women, three French academics who have an interest in Victorian culture. Emily Eells, a Professor at the Université de Nanterre, is a specialist in Proust – and therefore in the artistic vision of le beau monde. A Professor at Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Isabelle Gadoin is a specialist in Thomas Hardy – just as Hardy gave up prose for poetry at the turn of the century, Sargent renounced portrait painting in 1907 – and of Victorian Orientalism. Charlotte Ribeyrol is a Professor at Université Paris Sorbonne and honorary curator at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, where she notably co-curated Colour Revolution: Victorian Art, Fashion and Design in 2023.

It is interesting to read about the models for Sargent’s portraits, some of whom seem to have been as neurotic as Klimt’s Viennese ladies. Nevertheless, no matter how scandalous her portrait was, could Madame Gautreau qualify as a “professional beauty” (89), that is, as a courtesan? And when the ladies Alexandra, Mary and Theo Acheson were called “orange girls” in Punch, the idea was probably not that they were “orange pickers” (108), but rather orange sellers, after the fashion of Nell Gwyn…. While it is probably going too far to suggest that Sargent wished “to discreetly subvert the still overly white aesthetic of European neoclassicism in favour of that of a young, multicultural and multiracial America in the making” (403) because he sometimes used Black models, one is obviously thankful for the three authors’ cultivated and thoughtful reaction to his works; the abundant endnotes provide references for all the quotations from contemporary or modern critics.

As a wink at popular culture, much is made of the fact that Sargent’s works have often been used as covers for paperback editions of Henry James’s novels, which shows how much we project on those paintings. Beyond references to Downton Abbey (pp. 114 and 449), which does admittedly show “le beau monde et son revers”, one might also have expected an allusion to Julian Fellowes’ other famous series, The Gilded Age, where Sargent is actually seen painting the (fictional) portrait of young Gladys Russell, as one of the signs confirming her parents’ successful ascension to the highest spheres, even if they remain "new money" in the eyes of old New York.

Bibliography

Eells, Emily, Isabelle Gadoin and Charlotte Ribeyrol. Sargent. Le beau monde et son revers. Paris: Cohen&Cohen, 2025. 480pp. €135.00. ISBN 978-2-36749-129-5

Created 17 February 2026