This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the Historians of British Art, who first published it in their Winter 2011/12 Newsletter, pp.30-33. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also added captions and links. Click on the images for larger pictures and more information where available.

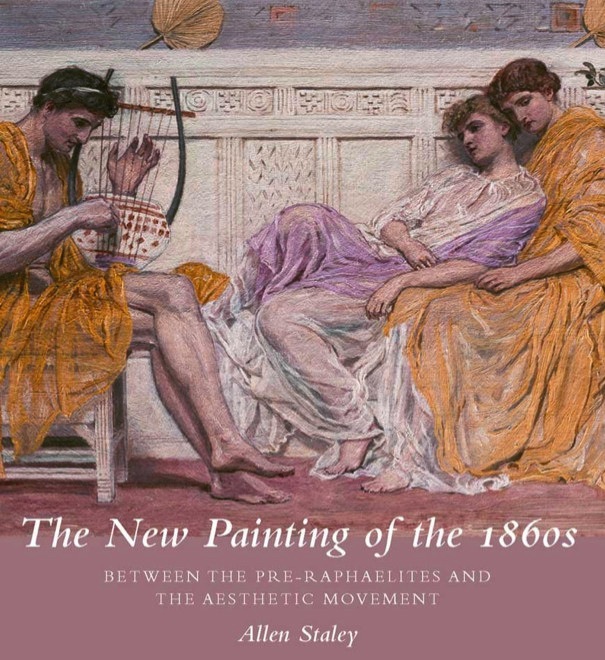

Readers will be familiar with Professor Staley's previous books on the Pre-Raphaelites, notably The Pre-Raphaelite Landscape (2001, with the same publishers), ultimately derived from his 1965 Ph.D. thesis at Yale. All this to say that The New Painting of the 1860s is literally based on the work of a lifetime, and one is constantly impressed by his admirable knowledge not only of the British painters whom he discusses, but of the contemporary French scene, let alone the Greek, Italian and Biblical background which inspired or illuminates so many of the works featured both in the copious text and the reproductions (most in full color) in this magnificently produced, large-size volume. His self-imposed remit is both simple and complex. The simplicity is in the sub-title: the author undertakes to examine "the 1860s" — the period "between the Pre-Raphaelites and the Aesthetic Movement." This commendable precision in the periodization, however, is largely annihilated by what Staley has to say in his Preface and Introduction: the period, which he first called "Post-Pre-Raphaelitism" (first as a joke, but now deserving serious consideration, he argues) imperceptibly merges into that elusive element, the Aesthetic Movement — and here is the rub (and the complexity), since many of his chosen names are usually associated with the Pre-Raphaelites or the Aesthetic Movement. This is in fact one of the major sources of confusion in the large "Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement, 1860-1900" exhibition that travelled from London to San Francisco via Paris in 2011-12: the Morris Sussex straw chair (c. 1860) was shown next to Alma-Tadema's opulently upholstered armchair (c. 1884/86), making visitors lose their bearings.

Left: William Morris's Sussex rush chairs, with their graceful simplicity. Right: The "opulently upholstered" Alma-Tadema chair (1884-86) in the "Cult of Beauty" exhibition, made of a variety of materials, including cedar and ivory. © copyright the Victorian and Albert Museum, London, with thanks.

Now, the pace of exhibitions on the Pre-Raphaelites and late-Victorian painters seems to be accelerating, with "The Cult of Beauty" already mentioned, "The Pre-Raphaelite Lens: British Photography and Painting, 1848-1875" and "Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer" shown in 2011, and "Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde" at the Tate Britain from September 2012. Likewise, on top of the often excellent catalogues to which they give birth, we have a constantly increasing output of books on the subject. In the Fall of 2011 alone, we had Fiona MacCarthy's The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination (Faber & Faber), a reissue of Alicia Craig Faxon's Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Abbeville Press; 1st ed. Oxford: Phaidon, 1989) and two new books on him, J.B. Bullen's Rossetti: Painter and Poet (Frances Lincoln) and Dinah Roe's The Rossettis in Wonderland: A Victorian Family History (Haus Publishing).

Autumn Leaves by Millais (1855-56).

In The New Painting of the 1860s, which constitutes a welcome addition to these recent publications, three prominent members of the original Brotherhood have their own chapters: Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Chap. 2), William Holman Hunt (Postscript 2), John Everett Millais (Postscript 3). The examination of the work of the last two is restricted to 1860-1869 for Hunt and 1856-1869 for Millais — hence the fact that they do not benefit from "proper" chapters. This reduction to "mere" Postscripts does not make them any the less interesting for that. In fact the opening paragraph of that on Millais explains the difficulty of any attempt at a hard-and-fast periodization in the field:

[In a previous chapter] I made a claim for Rossetti's Bocca Baciata [1859] as prophetic of the new interests of the 1860s. An analogous claim can be made for Millais's Autumn Leaves, but Autumn Leaves was painted mainly in the autumn of 1855 and exhibited in 1856, some four years before Bocca Baciata, and is usually seen as one of the masterpieces of the Pre-Raphaelitism of the 1850s rather than a precursor of what would come next decade. Nevertheless, it did mark major departures in content and in style from Millais's earlier Pre-Raphaelite works such as Christ in the House of his Parents or Ophelia. [375]

What Staley is driving at is the argument that what he calls "the new painting of the 1860s" was already germinating in paintings like Autumn Leaves, in the sense that Millais was already abandoning high-flying purposes (Ford Madox Brown criticized the picture precisely for that reason, Staley observes) by the mid-1850s. Indeed, this was not an isolated case but the first manifestation of Millais's adoption of a new, less lofty outlook because, Staley continues, "Millais followed Autumn Leaves with several subsequent non-narrative "mood-pictures," of which the most obvious sequel is a picture begun in 1856 and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1859 under the title Spring" (374).

Left: Frederick Sandys's Gentle Spring (exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1865). Right: Sir Edward Burne-Jones's oil-painting Laus Veneris (the watercolour of the same title dates from 1861).

The other full chapters are devoted to Frederick Sandys, Simeon Solomon, Albert Moore, James McNeill Whistler, Edward Poynter, Frederic Leighton, George Frederic Watts and Edward Burne-Jones. Staley in fact makes a point of emphasizing "the significance for their art of friendships between Rossetti and Burne-Jones, Rossetti and Whistler, Solomon and Moore, Whistler and Moore, Leighton and Watts, Watts and Burne-Jones" (343). Once again, however, the periodization is fraught with difficulties, with a lot of the works overlapping with what is conventionally called the aesthetic movement — the best proof of that being that these artists featured — sometimes prominently — in the recent "Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement, 1860-1900" exhibition. Bocca Baciata, for instance, is part of it, while Leighton's Pavonia, extensively discussed (and reproduced) by Staley, provided the image for the official exhibition poster and the dustcover of the Catalogue [shown at the top here]. Much the same could be said of Whistler (the Symphony in White trilogy), Sandys (Danaë and Gentle Spring), Watts (Choosing), Burne-Jones (Laus Veneris), Moore (A Venus) and of course Rossetti. Two artists however benefit from more attention in The New Painting of the 1860s: Poynter and Solomon.

Sir Edward John Poynter's Israel in Egypt (1867).

The chapter on Poynter will remind readers of the recent Gérôme exhibition, especially his Pollice Verso ("Thumbs Down", 1872), at the Phoenix Art Museum, which was featured on the cover of the Catalogue. Staley, who begins the chapter by observing that "[Poynter's] reputation has still not recovered" (183), does his best to present him in a favourable light but in The Catapult (1868), or even more so in Israel in Egypt (1867), the children of the 20th century that we are find it extremely difficult not to try to identify Charlton Heston flexing his muscles somewhere in some corner of the Technicolor CinemaScope composition.

Two Acolytes Censing, Pentecost, a watercolour by Simeon Solomon (1863) showing a typical concern with ritual.

Solomon's artistic life was ruined when he was arrested for attempted sodomy at a public urinal in 1873. Because of this, most of Solomon's seminal work belongs with the 1860s, Staley's chosen period, and the book naturally gives it extensive treatment, notably in the context of the "running nineteenth-century battle between prudish conservatives and progressive artists" (117). The complexity of some of Solomon's paintings possibly culminates in Sacramentum Amoris (1868) which, after describing it as "an emblematic image packed with arcane symbolism, partly pagan, partly Christian, partly Jewish, put to the service of what seems like a new, private religion" (113), Staley excellently analyzes in the light of the numerous comments which Solomon himself made of it to his patron Leyland. Staley's reader is left in no doubt that Simeon Solomon is a major figure of the 1860s scene, if only for his participation in the "classical revival of the 1860s" (176) "following on the heels of Pre-Raphaelites medievalism in the preceding decade" (110).

This provides an apt guiding thread for following Staley's undertaking: the 1860s could be seen a sort of crucible which saw the fusion of two sources of inspiration. As he convincingly puts it in his Conclusion, "A bit later, as the Pre-Raphaelites began to move away from their overweening attention to detail, their attitude toward subject also changed" (341). In other words, what we see in the 1860s is not so much the birth of the first elements of what was to become the Aesthetic Movement as the death of Pre-Raphaelitism in its initial, "pure" form. A sad, but alas probably true reflection, of course, for all admirers of the Pre-Raphaelite Movement.

This short review cannot do full justice to this remarkable volume, full of insightful connections between artists, techniques, sources and periods, and a delight to read for anyone, as it is written in exemplary jargon-free language, with no prior knowledge of the subject required. The strictly-focussed Bibliography includes articles, which is always very helpful, and the detailed Index makes the book a convenient tool for finding information on the works and their authors quickly. There is no doubt that it should be found in all Art College and University Libraries and recommended to undergraduates and doctoral students alike.

Related Material

- Aesthetic Pre-Raphaelitism

- Pre-Raphaelites in Focus (includes a review of The Pre-Raphaelite Lens: British Photography and Painting, 1848-1875

- Review of Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde

References

Staley, Allen. The New Painting of the 1860s: Between the Pre-Raphaelites and the Aesthetic Movement. New Haven (Conn.): Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art / Yale University Press, 2011. £50.00. ISBN: 9780300175677. Cloth. 438 pages.

Last modified 6 February 2014