After a three-page discussion of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Quilter turns to late Pre-Raphaelitism, at whose center he finds “three Oxford men”: Burne-Jones, Pater, and Swinburne. The following text, which I have transcribed from the near-perfect online text of the Hathi Trust, occupies pp. 395-400 of Quilter’s essay. — George P. Landow

he future direction of the movement, or rather of the results of the move ment, was mainly determined by the influence of a group of Oxford men, who in the three lines of painting, poetry, and criticism allied themselves to the dying cause, and who, though they entirely forgot the idea with which it had been started, and perverted its main doctrines, succeeded in endowing it with new life.

At this moment pre-Raphaelitism died as an instrument for regenerating art, and was at the same time re-born as a phase of artistic life, and furnished by the exertions of two or three poets and critics with new for mulas. Many artists too eccentric, too earnest, or too self-confident to work in the old methods, found a ready resting-place under the new banner, and it soon grew to be considered a sufficient claim to be a pre-Raphaelite if the artist's work showed a disregard of ordinary artistic principles, and an adherence to archaicism of treatment. In fact at this moment the movement, so to speak, crystallised — it became an end rather than a means; it began to extol mediaevalism in itself, not be cause of the qualities of simplicity, truth, and earnestness which had first led to the works of that period being selected as models.

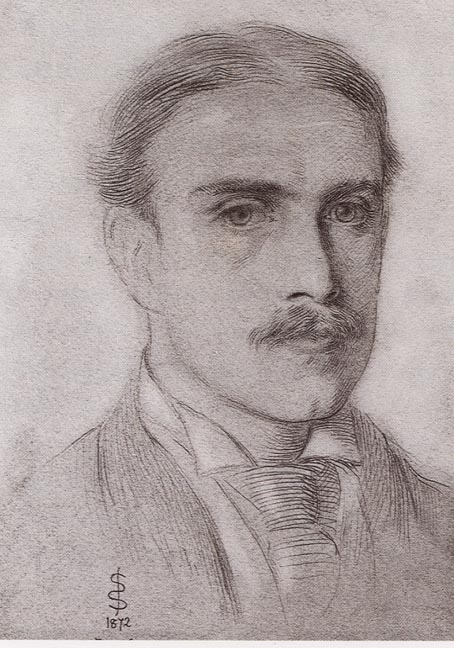

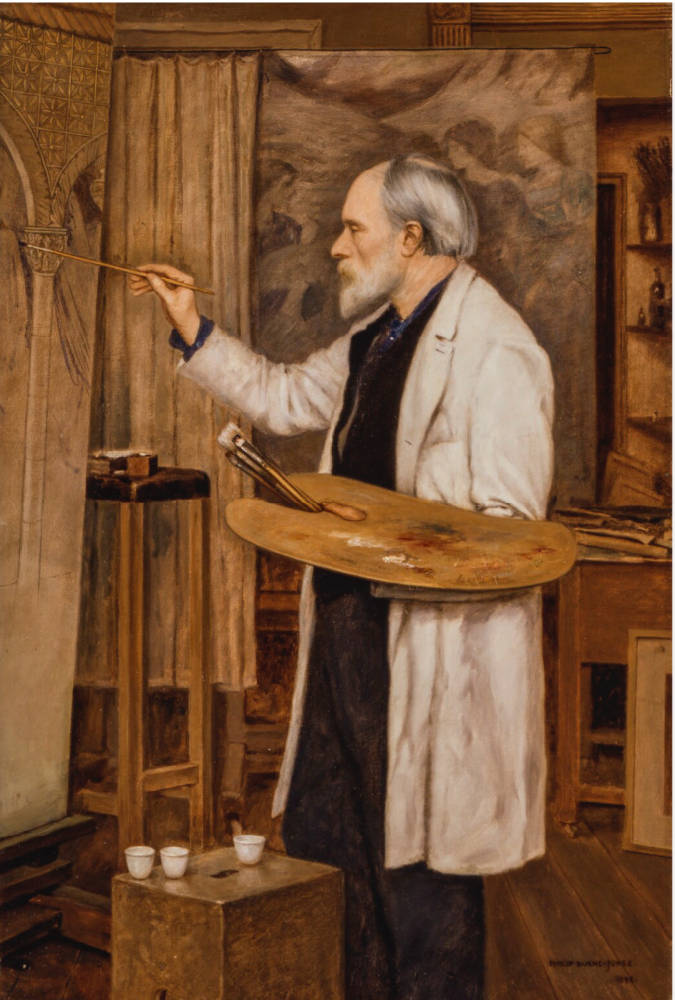

Left: Algernon Charles Swinburne. William Bell Scott. 1860. Oil on canvas, 47 3/4 x 31.7 inches. Middle: Walter Pater. Simeon Solomon (1840-1905). 1873 Pencil on paper, 30 x 21 cm. Right: Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt ARA by his son Sir Philip Burne-Jones. 1898. Oil on canvas, 30 in. x 20 1/2 in. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London NPG 1864. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

To return, however, to the new influences: these were chiefly embodied in Messrs. Swinburne, Pater, and Burne Jones — a poet, a critic, and a painter, all of them Oxford men, and all (if I remember right) contemporaries at the university. The painter's career was begun under the auspices of Mr. Rossetti, and soon showed the direction to be taken in the future by the school in question. The slightest acquaintance with this artist's pictures, especially his early works, suffices to make evident the enormous difference in aim which had now taken place. Perhaps the difference of spirit between Millais and Burne Jones in pre-Raphaelitism may be fairly likened to that between the art of Giotto and that of Botticelli, in which there is evident on the one side a loss of purpose and frankness of treatment, and, on the other, a growth of sumptuous colour and detail, and the substitution of over refinement and sweetness of ex pression for the vivid energy of the older painter. One curious resemblance to Botticelli which belongs to Mr. Burne Jones's work may indeed just be noticed in passing, which is the assimilation of the types of male and female; it is difficult, if not im possible to tell, in many instances, in either painter's work, the sex of the person represented. In what proportion the character of Mr. Jones's art was first determined by the influence of his master Rossetti, or by the poetry of his friend Mr. Swinburne, it would be excessively difficult to say: probably a genuine love of mediaeval art, and a somewhat melancholy temperament co-operated with both these causes; but it is cer tainly the case that in many ways Swinburne's poetry does leave its accurate reflection in the painter's pictures, and that from this time forwards the same note is continually struck by both men.

It is unnecessary to enter into any detailed account of the merits and defects of Mr. Swinburne's poetry; both are by this time generally ac knowledged, and the venomous criti cism and exaggerated praise bestowed so liberally upon the young author on the first appearance of his Poems and Ballads, have given way to more tem perate judgment No one now denies the beauty of many of the poems; no one either — at least, no sensible person — denies the unhealthy tone of the book as a whole. What concerns us here is not to pass a judgment upon either its beauty or its morale, but to explain very briefly what that morale was, because it formed one of the key notes to all the melodies of the later pre-Raphaelltes, and furnished the elements of the new "Gospel of Intensity." "Whither that gospel leads us, in art, in criticism, and in poetry, we can at present only guess, but I hope at some future day to bring some of its first infantile results before you.

The following verse from one of the Poems and Ballads, entitled "The Triumph of Time," puts the articles of the new creed before us plainly enough.

Sick dreams and sad of a dull delight;

For what shall it profit when men are dead

To have dreamed, to have loved with the whole soul's might,

To have looked for day when the day is fled?

Let come what will there is one thing worth

To have had fair love in the life upon earth,

To have held love safe till the day grew night,

While skies had colour, and lips were red.

Such is the note struck throughout these poems of Swinburne's; some times with fierce repining, sometimes with dull resignation, but always to the same intent. What shall it profit? That is the question he has to ask. What shall honour, truth, energy, unselfishness, whatever you will, that men have agreed to seek and honour, what shall they profit "when the day is fled"? Turn in imagination from this verse to one of the later pre-Raphaelite pictures — all have had an opportunity of seeing them since the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery — and think whether there could be a more accurately beautiful reflection of a poet's feeling than the reflection to be seen in, say, the great picture by Mr. Burne Jones, entitled, Laus Veneris.

Laus Veneris (In Praise of Venus) by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt ARA. 1873-75. Oil on canvas, 47 x 71 inches. The Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Very beautiful is this work, perhaps as beautiful as any picture that has been produced in our time; but what a sad, weary, hopeless beauty it is. Struggle against the impression as we will, the composition enervates and depresses us, in exactly the same way as the poet's words above quoted do. And now if one would feel the full difference between this and true pre-Raphaelite art, think for a moment of this view of love, and the one taken by Mr. Millais in that most beautiful and poetic of his pictures, The Huguenots. Note that in the first picture we are supposed to be looking at a scene of joy, and in the second at a scene of grief, and then let us ask ourselves whether we would not prefer the grief of the Huguenot, lightened as it is by the influence of truth and honour, to the joy of that Venus choir where truth and honour, and indeed all else, seem but "the shadow of a dream." And the sentiment of the picture

All passes, nought that has been is.

Things good and evil have one end;

Can anything be otherwise

Though all men swear all things would mend

With God to friend?

I do not intend to say a word on this philosophy beyond the statement of its motive, or rather its want of motive. What concerns us here is its enforcement by the new school. Rossetti's poems also were published about this time, and are in the main imbued with the same spirit, though they are neither so powerful nor so frankly material as those of Mr. Swin burne. The same melancholy hopeless ness is in them as in the work of the younger poet, but expressed less vividly and with far less spontaneity of feeling. Sensuousness is still the main thing to be desired, as melan choly is still the inevitable end of all things; but the sensuousness is of a cultivated intellectual type, hesitates here and there between the philosophic and the amatory — sometimes even fades out of sight in the enjoyment of the literary or artistic aspect of legend or nature. Love interrupted by death is the main subject of the majority of the poems, sometimes even love dreaming of a possible reunion beyond the grave. On the whole, Rossetti's poems glorify the passion of love in its abstract, instead of in its concrete, sense. The moral element is perhaps even more absent than in Swinburne, whose very rebel lion against morality seems to indicate a sense of it, which Rossetti appears to lack, unless the poem of Jenny be taken as an instance. In Jenny, however, the moralising is wholly ab extra.

So that here we have two great literary factors to take into account, the one a volume of poems inculcating a weary and hopeless passion, expressed in the most seductively beautiful music of which even our language can boast, and dedicated to an artist whose pictures express in colour, form, and intention the same ideas; and the other, an artist, publishing in mature years a volume of beautiful poems, written (we believe we are accurate in saying) chiefly under a sense of personal bereavement, and inevitably shadowed by such loss. Both books melodious in the extreme, both almost purely sensuous, both connected — one through friendship and kinship of feeling, the other through the author himself — with the new pre-Raphaelite idea.

Now it would have mattered little that Messrs. Swinburne and Rossetti, preachers as they were of a dreary gospel, should have been connected with, and champions of, a style of art which was tinged by the same melancholy as their poetry, had it not been the case that the very faults both of the poetry and the art, were such as to chime in with the deep intellectual unrest and shaken beliefs of the more thoughtful portion of our countrymen.

It was, to say the least, excessively unfortunate that at the very moment when a general desire for art had been awakened, and a general doubt of ancient formulas of belief aroused, there should be presented for accept ance by society an art of great beauty, but of inherent weakness, backed by a poetry which took as its chief tenet that nothing was worth the doing but "love."

There were but wanting now two things to aid the little group of poets and artists in the consolidation of their principles to render the lately vanquished pre-Raphaelite school a working social power. These were a sympathetic criticism, which, while omitting all the more debilitating effects of the poetry and art, should point out its essential beauties, and some link with practical life, whereby the influence could be extended over those people who cared little for poems and pictures, or for the criticism which expounded them. Nature, we are told by scientific authorities, never creates a want with out creating also the means for its supply, and accordingly, in the in stance before us, both requisites were forthcoming. A criticism of the required kind sprung up, headed by Mr. Pater and Mr. Swinburne, and the genius of Mr. William Morris, himself a poet and an artist, gave its main attention to the invention and supply of good decorative designs in accordance with mediaeval theories. The criticism which now started in aid of the new poetry and art was, in some ways, very notable. It was sympathetic in the highest degree with the objects of its laudation, and subtly suggestive of thought rather than actu ally thoughtful. It was, as we might have expected from its origin, scholarly almost to affectation, and was expressed with a seemingly accurate choice of beautiful words, the very sound of which was pleasant. It had, however, some great vices. Its praise was almost exclusively given to out-of-the- way people and things; poets and artists of very minor merit, long since forgotten, were dug up and held forth to the admiration of the disciples with praise which would have been fulsome if applied to Shakespeare. There was no medium in its judgments, no standard of comparison, no actual knowledge of the subject, save the fleeting and variable know ledge of emotional insight. The inner consciousness of the critic was taken as the first and ultimate judge in the matter, and as the inner con sciousness is often wrong when it reports on what it knows nothing about, the criticism was often very much astray. There were two other very great drawbacks. The first was that the critic's language often proved too strong for his meaning, and many of the sentences so ended that it was doubtful whether they had any meaning at all. The other drawback was, that the criticism was almost purely governed by personal feeling — and so the critics and painters got to be spoken of as the "Mutual Admiration Society." The temptation of course was very great for Mr. W. M. Rossetti to write complimentary criticisms of Mr. Swinburne, and who could com plain if Mr. Swinburne felt inclined to return the compliment.

In fact, the way in which the art, poetry, and criticism of the new school was mixed up was excessively curious, and will perhaps one day be fully known. As it is, we know that Swin burne wrote criticisms and poems, that one Rossetti wrote poems and painted pictures, and the other wrote criticisms on them, and so influenced both arts; that Burne Jones painted pic tures with motives from Swinburne's poems, and was at the same time in partnership with William Morris in his decoration business; that Morris wrote poems and made designs; and that Mr. Pater educated the public generally in the appreciation of what ever archaic and out-of-the-way art he could lay his hands on.

Other artists and poets soon followed suit, bringing other critics in their train. The decoration of Mr. Morris being really beautiful in its way, and very much needed as a protest against various upholstery abominations to which we had too long tamely sub mitted, grew and prospered prodigi ously. Art upholsterers and decorators followed the lead in every direction. The mystic words "conventional decoration" began to be used, a little vaguely but with the best intentions; the "Queen Anne revival" set in; and one aspiring tradesman even christened his chairs and tables as Neo-Jacobean! This last bold flight of fancy was, however, I believe, a failure, as I have not since heard it repeated.

At this period, when the poetry, and decoration, and criticisms of Swinburne, Morris, and Pater first came into fashion, it must be remembered that the central idea of the early pre-Raphaelites, that namely of painting occurrences as they happened, emotions as they actually appear, and nature as it actually looks, had practically disappeared. Mr. Holman Hunt was in Jerusalem struggling with the problem of Eastern sunlight and shadow; Mr. Rossetti was equally out of sight as far as his painting was concerned; and Mr. Millais, wholly free from his old prepossessions, was just entering upon that career of portrait-painting in which he has since had such marked success. The new poetry, beautiful as it was, and wholly devoted in spirit to that changed pre-Raphaelitism' of which Mr. Burne Jones stood at the head, was singularly inconsistent with the first tenets of the school. In place of the simple frankness of spirit, at which Millais and Hunt had aimed, it substituted a refined and weary cynicism; in place of showing things as they were, it depicted them as they were not, and as, fortunately, they never could be; in place of holding the belief that the subject-matter of art was far broader than was commonly allowed, it substituted the doctrine that there was only one subject worthy of painting or writing about, and that was — Love. Now we should be doing great injustice to the poets, artists, and critics whom we have just mentioned, if we did not at once confess that their work was in the main good of its kind. The accusation which is rightly to be made against the clique is that their whole object was an unworthy one, that it inculcated a philosophy of life and morality out of which it was impossible that healthiness of thought or feeling should come, or with which it could co-exist, and sought to turn all the power of art and poetry not to the improvement of the race, but its injury. The philosophy of its criticism and painting stood at the very opposite pole to Ruskin's great definition of the best art, and instead of maintaining that art to be the finest which embodied "the greatest number of the greatest ideas" held that the province of art was altogether exclusive of ideas, and that the fewer ideas there were contained therein, the finer was the art. For instance, according to one of the later and lesser lights of this school, Shelley's poetry was judged to be on a distinctly lower level than Keats's, simply and solely be cause there were to be found therein certain great intellectual ideas! These, the critic remarked naively, had no business there, and he — like Mr. Podsnap in Our Mutual Friend — " waved them off the truth."

Well, this poetry and art worked its way a little into the public mind, and a similar criticism commented on and explained the doctrines of pure sensuousness in art, as above hinted at. Morris's decoration began to be popular, and to overspread our houses, and even touch and alter the dresses of our women, and still no one seems to have suspected the healthiness or the advantage of the movement. Papers and magazines teemed with panegyrics eloquently incomprehensible except to the initiated, in favour of conventional art and erotic poetry — from the inner consciousness of critic after critic, we received instruction upon the merits of "solid sensuousness"; with one accord all reference to English art was considered to be Philistine, and nothing was allowed to be praised as worthy of later period than what the prophets termed the Early Renascence. From the recesses of Oriel College Mr. Pater took every now and then dives into mediaeval French or Italian history, emerging triumphantly with some firmly-clutched improper little story which he had rescued from the oblivion into which it had unfortunately fallen, or with the name of some forgotten painter, too long allowed to slumber in peaceful obscurity. Swinburne was no less active in the intervals of his poetic labours, and brought many a buried or misconceived genius before the glare of our modern footlights. Morris's business, and his epics, both expanded, and at last, only yesterday as it seems, the Grosvenor Gallery opened, and gave to the movement its final fashionable influence. Imitators and admirers had by this time sprung up all round, especially among the women, and the first Grosvenor Exhibition, witnessed the curious sight of the now greatest master of the new school, surrounded on all sides by the works of his followers, and as Mr. Ruskin said at the time, in a famous number of Fors Clavigera, the effect of the master's work was both " weakened by the repetition, and degraded by the fallacy" of its echoes.

Behold, then, a new philosophy of art and life, sanctioned by the aris tocracy, and supported on all sides by an admiring, and what the Americans would call a "high falutin'," criticism. Can we wonder at the success attained? Here, indeed, was a gospel suited to cultured England, the very first article of whose creed was "Whatever is, is wrong " — a curious result this of scientific discovery and nineteenth century progress in general culture and enlightenment, that melan choly should be discovered to be the summum bonum, that the great object of art was to express, in words or colours, that there is

A little time for laughter;

A little time to sing;

A little time to kiss and cling.

And no mor kissing after.

Cast your recollection back for thirty or forty years before this new light had broken upon us, and try to imagine what Turner, or De Wint, or David Cox, or even old William Hunt, would have thought of our new theories. Fancy inviting the painter of the Hay Field and the Welsh Funeral to a modern aesthetic "at home," or explaining "the sweet secret of Leonardo" to Hunt while he painted Too Hot or the Listening Stable-boy! Fancy a young lady asking Turner if he was "intense," or reading "Eden Bower's in flower" to De Wint as he sat sketching in the muddy lanes under the gray skies, which he knew so well and (curiously as it now seems to us) loved so dearly. And yet why should these suppositions sound so ludicrous? Surely all fine art has ties of blood-relationship, and we have not yet got so far as to deny that Turner, Cox, De Wint, and Hunt were true artists!

Is it possible that somehow our revival has strayed "off the line," and is wandering in mazes of false feeling and morbid affectation? Is it pos sible that, after all, melancholy is not the key to all fine art, and that even a return to the "Early Renascence" will not compensate us for the loss of healthy national feeling? Is it pos sible that Hunt's motto, still to be seen on one of his pictures, "Love what you paint and paint what you love," is a truer one than "Love no thing but regret, and regret nothing but love"? And lastly, is it possible that this self-consciousness of a miserable, thwarted, and limited existence — this conception of the world as a place where effort is absurd and action futile, and where the only vital thing to remember is

"That sad things stay and glad things fly

And then to die —

is it possible that such a creed as this is unworthy of English men and English women, and is poorly com pensated for by a little increased knowledge of the peculiarities of early Italian artists, and a morbid love of medIeval ballads?

It is too soon to trace the effects which will surely follow the spread of the present fashion. If Mr. and Mrs. "Cimabue Brown," "Maudle," and " Postlethwaite" are to become permanent facts in our social system; if the mutual-admiration societies, and the " intense " young ladies who have lately been so well satirised for us by Mr. Du Maurier, still continue to increase as they have done of late; if our women's dresses and drawing-rooms continue to present a combination of dreary faded tints, dotted here and there with spots of bright colour; if china must still be hung upon the wall, and parasols stuck in the fire place; if our houses continue to assume the appearance of a compromise between a Buddhist temple and a Bond Street curiosity-shop; if the cultivation of hysteric self-consciousness continues to be considered as a sign of artistic faculty, and the incomprehensibility of art-criticism to be a guarantee of its profundity; if we still continue to think that no art is worthy of examination which has been produced since the time of the "Early Renascence"; if, in a word, the present fashion continues to live and flourish amongst us, if we can't have art at all unless we have art of the kind I have mentioned, with results to match — why then, in Heaven's name, let us "throw up the sponge" without further contention — let us become frankly and thoroughly "Philistine," as were our fathers. Very certainly there is more hope for a nation in thorough but loving ignorance of art — caring, for instance, for pictures in the way a child cares for a picture-book — than in a state of knowledge of which the only result is a sick indifference to the things of our own time, and a spurious devotion to whatever is foreign, eccentric, archaic, or grotesque. I may perhaps try to show my readers in a future article a few of the more evident absurdities in volved in the new criticism and deco ration; for the present I bid gladly adieu to the worst gospel I have ever come in contact with — the "Gospel of Intensity."

Harry Quilter.

Related material

- Aesthetic Pre-Raphaelitism

- Some European descendants of Pre-Raphaelitism: Khnopff, Klimt, Klinger, and Others

Bibliography

Quilter, Harry. “The New Renaissance; or, The Gospel of Infinity.” Macmillan’s magazine. 42 (1880): 391-400. The Hathi Trust Digital Library online version of a copy in the Princeton University Library. Web. 30 November 2019.

Last modified 30 November 2019