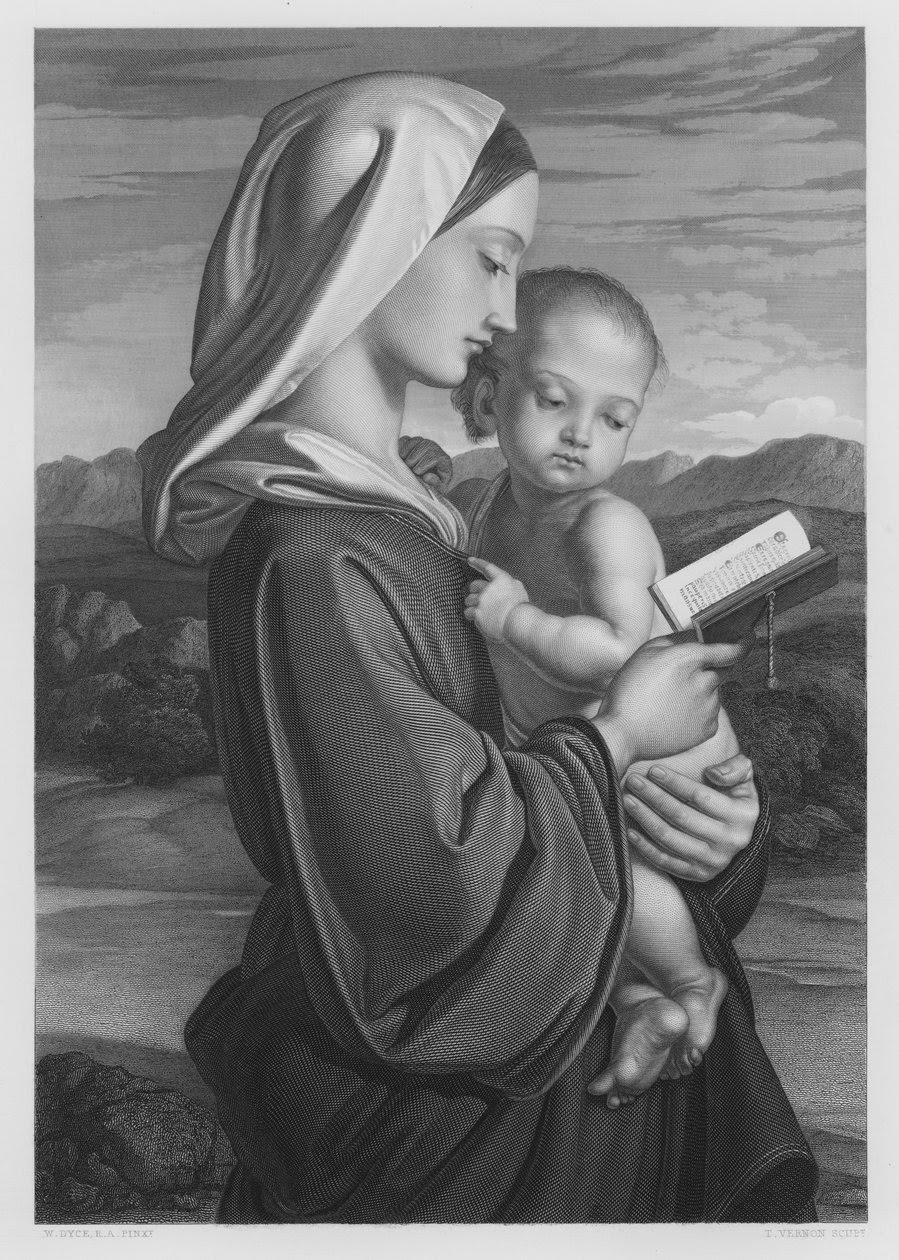

Left: Madonna and Child [Virgin and Child] c.1845. Oil on plaster on slate. 31 x 23 3/4 inches (78.7 x 60.3 cm). Collection of the Nottingham City Museum and Galleries, accession no. NCM 1910-53. Image courtesy of Nottingham City Museum and Galleries, via Art UK under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence (CC BY-NC). Right: The Virgin Mother, 1855. Etching and engraving by Thomas Vernon after William Dyce. 13 ¾ x 10 ½ inches (34 x 26.7 cm) – sheet size. Private collection. Image courtesy of the author. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

This painting is likely a preliminary study for the painting in the Royal Collection that was shown at the Royal Academy in 1846, no. 451. It is one of the series of paintings of the Madonna and Child that Dyce produced between 1827 and 1845. The study portrays the Virgin Mary holding Jesus with her left arm while reading from a small red book held in her right hand. Her hair is braided at the back and not covered by the white hood seen in the final composition. She is wearing a red round-necked dress with large sleeves edged in green. Her blue cloak has slipped to waist level. The Christ child is naked except for a band of white fabric slung over his right shoulder. Although the figures of Mary and the baby Jesus are highly finished, the background is an ill-defined sketchy rocky landscape as compared to the final version at Osborne House.

The Influence of Italian Renaissance Painting

Anne Steed has discussed this work in its relation to Renaissance prototypes:

The simple, even austere image, of the bareheaded version, with the figures silhouetted against the sky, has an iconic quality. Dyce has created an archetypal mother/Madonna. The strength of the painting lies in its absolute stillness, which draws us into its meditative calm. The classical severity of the outline of the full profile pose is more pronounced. This hard-edged clarity is characteristic of the work of Sandro Botticelli and although the profile head is a common motif in Renaissance art, the figure types and the features of the Madonna and Child suggest Dyce was looking at Botticelli quite particularly. Dyce was in Italy in 1845, looking at fresco painting, and evidently made a close study of the Master's style, as well as his materials. The gentle supporting hand of the Madonna, firmly cupping the Christ child's bottom, gives the impression of having been observed from life but may also derive from Renaissance art. At least two of Raphael's Madonnas use the same intimate embrace and Raphael had, it seems, borrowed the pose from Donatello. [108]

When the work was exhibited in Forli in 2024, Tim Barringer related this preliminary study to the later finished version:

A later Madonna and Child (1845, Royal Collection), acquired by Prince Albert, reveals Dyce’s developing study of earlier Italian painting. The influence of Raphael is prominent and Queen Victoria herself described the work as ‘quite like an old master & in the style of Raphael.’ Nonetheless, the self-consciously archaic use of profile may acknowledge the artist’s admiration for Italian quattrocento panel portraits, while the colouring and tonality pay homage to Giovanni Bellini. Dyce's involvement in the design of a new coin, known as the Gothic Crown, was cited by Marcia Pointon as a possible source of this severe profile. The Virgin and Child from Nottingham displayed in the exhibition and connected to the painting from the Royal Collection is unusual for having a support similar to that of fresco: the plaster spread on the slate produces an opaque surface. It is possible that the work is the result of an experiment conducted by Dyce as he was preparing to create an ambitious cycle of frescoes for the Palace of Westminster. The heavy drapery and the linear and well-defined representation of the Madonna's face and hands indicate a greater interest in the art of the past. Raphael's bewitching influence persists in the delightfully joyful rendering of the Child's head, reminiscent of the Great Cowper Madonna (1508, Washington, National Gallery of Art) which in Dyce's time was widely reproduced in England in printed publications. [496]

Steed has speculated that perhaps Dyce's early version on plaster was seen by Prince Albert who then commissioned the oil (see p. 108).

Another art historian, Allen Staley, considers that The Madonna Dyce painted for Prince Albert was influenced by both Raphael and Quattrocento profile portraits, and feels it is more Italianate than any of his later Pre-Raphaelite pictures. He notes that Dyce's landscape background of generalized mountains is thinly painted on a white ground with precise outlines but little detail, and feels it is only of minor importance to the composition (see p. 163).

The Relationship to Dyce's "Osborne Madonna"

Referring to the painting in the Royal Collection as the "Osborne Madonna," Marcia Pointon feels that it was ahead of its time for an English work: "The Madonna in the Osborne painting reminds us of quattrocento profile-portraits and, like Raphael's Madonna of the Goldfinch, she holds a Bible in which scraps of writing, looking like the prophecy regarding the Son from Isaiah, are discernible. But the Osborne Madonna is dressed in a heavy, loose-sleeved tunic very different from the clothing of Raphael's Virgin…. The unusual qualities of the Osborne Madonna were grudgingly acknowledged by the press" (87). Pointon finds the result "too German and too 'avant garde' to appeal to a wide public and yet, only a few years later, a taste for German art and a revival of interest in late medieval and early Renaissance painting became widespread. People were far more inclined to view the work of quattrocentisti or the 'primitive' productions of Nazarene artists with approbation and a serious regard in 1850, than they were in 1845" (88).

Contemporary Reviews of the Picture

On the whole, reviews of the painting on its exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1845 were rather mixed. The influence on it of both the Nazarenes and the Italian Primitives was quickly recognised. The Art-Union critic, for example, noted that the work

refers at once to the masters of the Italian school antecedent to Raffaele, being painted in the style prevalent in the German school of religious painting. The Virgin is represented standing and holding the infant in her arms, and at the same time a book, upon which her eyes are cast. As an example of the period to which we allude, the work is possessed of merit of a very high order. It is distinguished by the sentiment with which the early masters strove to view their works, and without the errors into which they fell. The colouring is flat like fresco, and the contours have the well-known severity of the style. The head is like that of a Madonna by Masaccio, in one of the Florentine churches; but the resemblance may be accidental. [181]

Surprisingly, in Germany, where Dyce might have expected to find approval for art based on a simple linear composition and sincere Christian feeling, another critic found it to be somewhat cold in expression and colour. In 1847 a report published in The Art-Union, quoted from the German publication, the Kunstblatt, in which Dyce's Madonna and Child is mentioned in the larger context of British art: "W. Dyce is of the small number of those who, approaching the Perugino–Raffaele time, follow the principles of the school of Overbeck. His Madonna with the Infant Christ in this exhibition is of unique appearance; it is graceful, but somewhat cold in expression and colour" (21).

Looking at the work in the same larger context, but from a rather different point of view, the Art Journal critic of 1855 discussed the related painting of the Madonna and Child in the Royal Collection at Osborne House, and suggested that Dyce had sought to defend the English School from charges of being incapable of executing serious Christian art:

The treatment of his Virgin Mother is very graceful and expressive: she is walking in an open landscape, reading, and her thoughts are evidently fixed upon the prophetic passage from Isaiah, inscribed on the open leaf: "And there shall come a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots." The Child appears to be divining her meditations, and directing them by pointing to her as the "Stem of Jesse." The faces of the two figures are sweetly rendered, and full of devotional feeling. The colouring of the picture is rich and harmonious: the dress of the Virgin is a deep crimson, the loose robe of dark green, edged with golden lines, the hood a pure white, the sky and distant hills are a deep blue, and the whole of the middle distance is painted in a low, warm tone of olive green. The picture was purchased from the Royal Academy exhibition of 1845. [76]

A sign of approval was the appearance of Thomas Vernon's engraving in this same 1855 volume of the Art Journal (between pp.76-77). This was reproduced in an earlier version of this web-page by George P. Landow, who also quoted from a review printed later in the volume: "Mr. Dyce in his Virgin and Child has emulated the style of the old Italian masters, such as John Bellini, Cima di Conegliano and Perugino‚ and, has filled up a contour of gothic sharpness with tints happily attenuated. This quaint pasticcio is skilfully enough made out" (251).

To echo Pointon, there is something a little grudging at the end there ("skilfully enough"), which is amplified, finally, by the Spectator reviewer of the time. Unimpressed by Dyce's rather traditional but run-of-the-mill treatment of the subject, this reviewer complains: "the Virgin mother seems to forget that she holds the infant Saviour, while intent on the pages of a prayer-book! Character and sentiment are the body and soul of art; and the vital genuine expression of familiar subjects and feelings has a stronger charm than the repetition of typical forms and worn-out conventionalities" (474).

Bibliography

Barringer, Tim. Preraffaelliti Rinascimento Moderno [Pre-Raphaelites Modern Renaissance] . Milan: Dario Cimorelli Editore, 2024, cat. II.3, 496.

Bell, Quentin. "The Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Art-Union VIII (1 June 1846): 171-89.

"Fine Arts. Royal Academy Exhibition." The Spectator XIX (16 May 1846): 474-75.

"German Criticism on British Art." The Art-Union IX (1847): 21.

Pointon, Marcia. William Dyce 1806-1864. A Critical Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979.

"The Royal Pictures. The Virgin Mother." The Art Journal New Series I (1855): 76. The engraving is available here in the copy from the University of Michigan Library, on the HathiTrust website.

Staley, Allen. The Pre-Raphaelite Landscape. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1973.

Steed, Anne, William Dyce and the Pre-Raphaelite Vision. Ed. Jennifer Melville. Aberdeen: Aberdeen City Council, 2006, cat. 18, 108-09.

Virgin and Child. Art UK. Web. 15 December 2024.

Created 15 December 2024