Transcribed from the Hathi Trust, with extra paragraphing, and illustrations from our own website, by Jacqueline Banerjee. See Bibliography for details of source. Note that the links to related material contains one to a Spotify playlist (click on this, and sign up for a free account), suggested by our music editor, Amy Hunsaker. This provides many examples of music popular in the Victorian era.

t was only during the last twenty-five years of the nineteenth century that the Renaissance of English composition gradually grew from more to more; but in other departments of music signs of the new order were visible at an earlier date. In 1855 August Manns (1825-1907) started at the Crystal Palace a lifetime's work that has had a great and most beneficial influence; not only did he first introduce to English audiences the orchestral compositions of Schubert and Schumann and many more, but it is to him, foreigner though he was by blood, that nearly all our principal living composers owe their first public encouragement.

Spy's take on Sir August Manns in Vanity Fair.

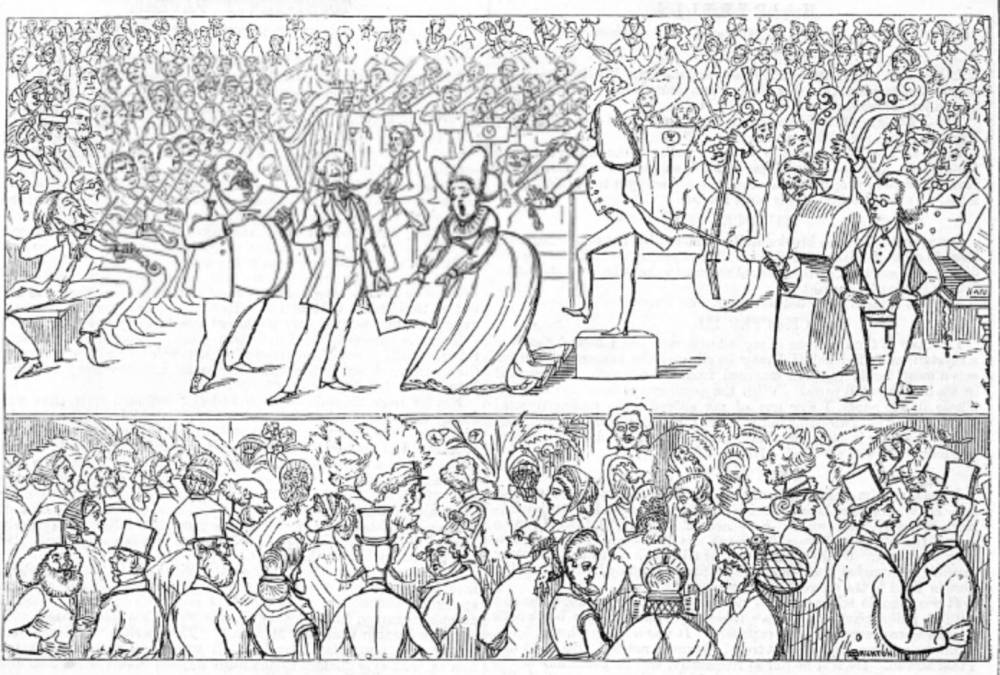

Manns' labours were ably seconded by George Grove, for many years Secretary to the Crystal Palace Company, and subsequently the first Director of the Royal College of Music (who was also the real inventor of the [286/87] analytical programme, and the editor of the first complete Musical Dictionary in the English language); and in the field of chamber-music the St. James' Hall Popular Concerts, started in 1859, did a great work in familiarizing the English public with the finest renderings of all the classical masterpieces (though it was no part of their manager's scheme to make experiments or to do anything for native composers), and, from 1848 onwards, Charles Hallé did valiant service in a similar direction, in London and the North of England. Of late years (largely owing to the enthusiastic labours of Henry J. Wood at the Queen's Hall) the popularity of orchestral concerts has increased so much that it distinctly threatens to silence the quieter appeal of chamber-music; but in spite of this very regrettable fact, nothing shows better the enormous advance in musical appreciation than a comparison of the programmes of a "Promenade Concert" at Queen's Hall to-day and of its parallel a generation ago, when the Crystal Palace had a virtual monopoly of symphonic music in or near London.

In vocal music, however, the revival came somewhat later. The older generation of living solo singers has not felt to any appreciable extent the same pressure towards the universal choice of high-class music which is becoming every year more and more weighty; it is only the younger singers who feel obliged to render at least an outward homage to the ideal which has long ruled in the instrumental field. In choral music, again, it is only comparatively recently that we have recognized that something more than mere military drilling is necessary in modern technique; and the new era of opera is altogether little more than twenty years old.

But in every department, plentiful as are the opportunities for deeper culture that still remain, the advance that has coincided with the renaissance of composition has been very remarkable; an English-born and home-staying musician has now a position of perfect artistic equality with his continental colleague. Again, we can see in the teaching world how the old Royal Academy was awakened to a new existence by the establishment of the Royal College in 1882, and how they, with other institutions and individual teachers, have moved with the times in raising the average quality of the music taught to [287/88] young people - distant even yet as is the goal. And we cannot pass by the Tonic Sol-fa movement [the Association was founded in 1853, the College in 1869], which has had enormous influence in diffusing elementary musical knowledge among certain classes of the community; it has indeed been often greatly hampered by a quite unnecessary connexion with musicianship of the very poorest kind, but freed from these shackles and taken for what it is - merely an easy means to the end which all musicians have in common, and not a sort of panacea that can afford to dispense with the one universal language of the staff notation - it should do a lasting work in English music.

The Royal College of Music, 1894, designed by Sir Arthur Blomfield.

The People's Concert Society (founded in 1878) and others of similar aims have done finely artistic work in the poorer quarters of London, and the more recent Competitive Festivals have very greatly fostered good music in provincial districts; indeed, though ... the wide diffusion of music among relatively uneducated persons has often had the great drawback of extinguishing the memory for traditional folk-songs, yet it has proved — what we ought to have known before — that artistic appreciation is quite independent of social distinctions, and that there is no sort of foundation for the pernicious doctrine that it is ever necessary for a musician to sing or play down to the supposed level of any audience in existence. And simultaneously the musician himself has become far less narrowly professional, far more interested in the whole wide world of intellect and art; a hundred years ago he was far more alien to his average cultured fellowman than he is to-day, and the change is all for the good.

So far as the concert-room forms are affected, the new course of English composition has progressed steadily onwards, and no special individual features are noticeable: plenty of very inferior work, especially vocal, has no doubt been written, but still the standard of musicianship expected has gradually and firmly been rising for the last quarter of a century, and the ground under our feet is now perfectly [288/89] solid.

Links to related material

- Music in the Era of Queen Victoria

- Music and Social Class in Victorian England

- (offsite) Victorian Music: A Playlist of Music in Britain between ca. 1835 and ca. 1915 by English, British and European composers who lived in Britain during the Victorian and Edwardian Periods. Includes also classical music favourites of Queen Victoria & music of nineteenth-century India on Spotify

Bibliography

Walker, Ernest. Music in England. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1907. Hathi Trust. Contributed by the New York Central Library. Web. 15 August 2022.

Created 14 August 2022