As printers and publishers, the Foulis brothers were famous for their magnificent editions of the classics, such as their splendid folio editions of the Iliad and Odyssey (1756-58). On the other hand, the great majority of the Foulis brothers’ book output consisted not of sumptuous showcase quartos and folios but of workmanlike octavos and duodecimo editions of classical and modern authors.” — Andrew Hook and Richard B. Sher, eds., The Glasgow Enlightenment, p.13

“As the eye is the organ of fancy, I read Homer with more pleasure in the Glasgow edition. Through that fine medium, the poet’s sense appears more beautiful and transparent.” — Edward Gibbon quoted in Murray

orn in Glasgow in 1707, the son of a barber and maltman, and apprenticed in his turn to a barber, Robert Foulis practised the trade as a Master Barber until 1738. He managed, however, to attend classes at Glasgow University (then known as the College) and, as of 1730, enrolled in courses taught by the professor of Moral Philosophy, Francis Hutcheson, one of the founding fathers, along with Hume, Smith and Ferguson, of the Scottish Enlightenment. He also took classes in Latin and Greek literature (Bonnell, p. 46). Hutcheson thought well enough of his student, to appoint him a tutor in his classes, and it may well have been Hutcheson who encouraged him to become a printer and bookseller and thus spread the “zeal for classical learning,” shared by teacher and student, among the wider population. Robert Foulis’s younger brother Andrew had a more formal education. He studied Humanity (still today the Scottish universities’ term for Latin) at the University, and later taught Greek, Latin, and French in Glasgow. He even applied – unsuccessfully -- for the chair in Greek at the University.

Robert Foulis by James Tassie, Courtesy of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery PG 137. Click on image to enlarge it

In 1738 while on a trip to France, the brothers purchased a number of books, exported them to Britain, and successfully sold them in London and Glasgow. Three years later Robert opened a bookshop at the College in Glasgow and almost immediately began to publish books himself. At first they were printed by other firms, but within a year Robert Foulis had his own press and in 1743 was appointed the University’s printer. For many years, the Foulis bookshop served as “a pleasant lounge and meeting place for students and others interested in books and literature,” anticipating in a small way publisher and fellow-Scot John Murray’s drawing room at 50 Albemarle Street in London. Though relatively small, the Foulis Press turned out almost 600 editions in the years between 1742 and 1776.

Using quality paper and fine typefaces made locally by Alexander Wilson, an expert in the field, Robert and his brother Andrew, who had joined the firm towards the end of 1746, quickly established a Europe-wide reputation as “the Elzevirs of Britain” for their well designed and immaculately executed editions of ancient classical texts, some printed in Greek alone, or Latin alone, some in Greek with a Latin translation, and some in English translation. In one of the rare studies devoted to the brothers and their press, it is claimed that Winckelmann never travelled without Homer, “his companion at every instant of his life,” according to the Life of Winckelmann, and that “the edition he had with him on his last journey (in the course of which he died) was that of Foulis, ‘very elegantly printed at Glasgow in 1756-58’” (Murray, p. 26).

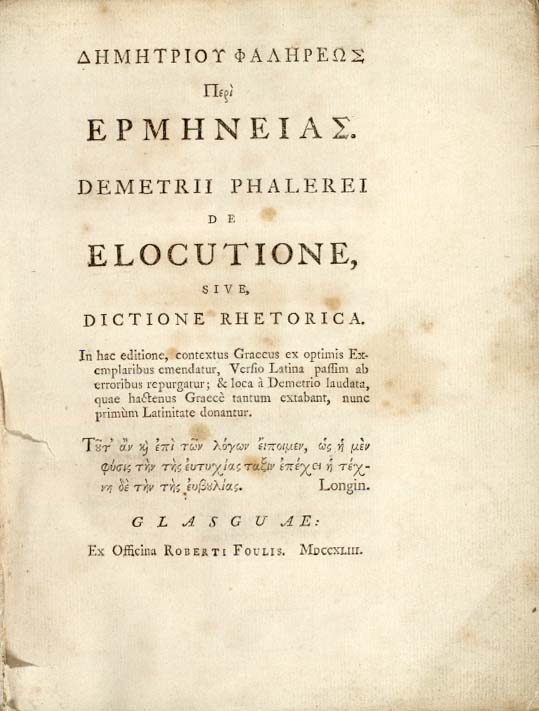

The title-pages of two works published by Robert Foulis.

Although a fair number of their books were produced specifically for collectors of select works and were printed on large and fine paper, vellum, linen and satin – Robert’s ideal printer was in fact not the Elzevirs but the great sixteenth-century French printer Robert Estienne or Stephanus -- the Foulis brothers also published many more, relatively inexpensive “workmanlike octavos and duodecimos” of both ancient and modern classics, as well as of the writings of professors at the College, such as Robert’s mentor, Francis Hutcheson, the social and political theorist John Millar, and the orientalist and natural scientist John Anderson (founder of Anderson’s Institution, dedicated to natural science, and now the University of Strathclyde). While the Foulis’s widely admired folio and quarto editions of the classics were not always profitable and were expensive to produce – Robert’s ultimate ideal of a folio edition of Plato, decades in preparation, was never realized -- these manageable pocket-size volumes, intended for students and the general reader, were widely appreciated and were what kept the press afloat financially, even though much effort was devoted to achieving high textual accuracy. The brothers employed a proof reader, which was not common practice at the time (Bonnell, p. 47).

The ancient classics were represented among the less elaborate volumes by editions, sometimes in the form of the author’s complete works, of Aeschylus, Anacreon, Aristophanes, Aristotle, Caesar, Cicero, Cornelius Nepos, Demosthenes, Epictetus, Heliodorus, Herodotus, Homer, Horace, Juvenal, Longinus, Lucretius, Marcus Aurelius, Phaedrus, Pindar, Plato, Plautus, Pliny, Plutarch, Sappho, Sophocles, Tacitus, Terence, Theocritus, Theophrastus, Thucydides, Virgil, and Xenophon. The moderns included, not only well established classics such as Shakespeare, the fifteenth to sixteenth-century Scottish poet William Dunbar, Milton, Thomas More, Dryden, Thomas Otway, and Locke, and relatively recent writers, such as Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, Congreve, John Gay of The Beggar’s Opera, Pope, Matthew Prior, Nicholas Rowe, Shaftesbury, and John Vanbrugh, but several contemporaries -- Tobias Smollett, Samuel Johnson, Edward Young (of Night Thoughts), and Thomas Gray (of the celebrated Elegy). A deluxe quarto edition of Gray was even produced, which won general acclaim, not least from the author himself. “I rejoice to be in the hands of Mr. Foulis, who has the laudable ambition of surpassing his predecessors the Etiennes and Elzevirs,” Gray declared (cited by Murray, p. 95). In addition, the brothers published translations of Boileau, Bossuet, Cervantes, Fénelon, Le Sage, Tasso, and Voltaire. Their achievement, as described by Richard B. Sher and Andrew Hook, “was to translate into print culture the values of the classical, aesthetic, moralistic, Hutchesonian Enlightenment in Glasgow” (p. 13).

Never a very large firm like Murray or Strahan or Constable, the Foulis Press shut down at the end of the century. Its financial status had become precarious even before it was taken over by Robert’s son Andrew, following the older Andrew’s death in 1775 and Robert’s a year later. Increasing concentration on the popular duodecimo editions could not make up for the losses entailed by the firm’s high quality quartos and folios and Robert’s longtime and passionate commitment, which he had pursued at great expense, to founding a local Academy of Art. Nevertheless, it had an impact on the culture of its time – and of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries — well beyond Glasgow or Scotland. Robert and Andrew Foulis, it has been said, were not only “the ‘most important of the British classical publishers’ in the eighteenth century, their pocket editions of English poets, begun in 1765, spawned a publishing phenomenon that has thrived from that day to this, from their own series to the Oxford World Classics.” It is indeed ironic, in the words of the same scholar, “that printers such as Robert and Andrew Foulis, deeply imbued with the old-order ethos of a Robert Estienne, should have helped to pave the way for a mass market in poetry reprints, but that is what they did” (Bonnell, pp. 1, 51).

Spreading the Word: Scottish Publishers and English Literature 1750-1900

- Scotland and the Modern World: Literacy and Libraries

- Scottish Publishers, London Booksellers, and Copyright Law

- Andrew Millar (London) 1728

- William Strahan (London) 1738

- Robert and Andrew Foulis, The Foulis Press (Glasgow) 1741

- John Murray (London) 1768

- Bell & Bradfute (Edinburgh) 1778

- Archibald Constable (Edinburgh) 1798

- Thomas Nelson and Sons (Edinburgh) 1798

- John Ballantyne (Edinburgh) 1808

- William Blackwood (Edinburgh) 1810

- Smith, Elder & Co. (London) 1816

- William Collins (Glasgow) 1819

- Blackie and Son (Glasgow) 1831

- W.& R. Chambers (Edinburgh) 1832

- Macmillan (Cambridge and London) 1843

- Lesser Publishers

- Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-century British Copyright Law: A Bibliography

Bibliography

Bonnell, Thomas F. The Most Disreputable Trade. Publishing the Classics of English Poetry 1765-1810. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Pp. 30-60.

Hook, Andrew, and Richard B. Sher, Ed. The Glasgow Enlightenment. East Linton: The Tuckwell Press, 1995, p.13.

Murray, David, and Robert. Andrew Foulis and the Glasgow Press. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons, 1913.

Sher, Richard B., “Commerce, Religion and the Enlightenment in Eighteenth-Century Glasgow,” in Glasgow, Vol. I: Beginnings to 1830. Ed. T. M. Devine and Gordon Jackson. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1995. Pp. 312–59.

Gaskell, Philip. A Bibliography of the Foulis Press. Winchester: St. Paul’s Bibliographies, 1986.

Last modified 15 November 2018