Sir Francis Seymour Haden (1818-1910) was born in Sloane Street, London SW1. The son of a physician, he was educated at University College School, going on to study medicine at University College, London, then at the medical school of Grenoble, and at the Sorbonne in Paris. He achieved prominence as a surgeon, only taking up etching seriously in 1857 — the very year in which he was elected Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. After that his hobby became an important part of his life. The following article was originally written for the Journal of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers (No. 7, 1985), and is reproduced here by kind permission of the author, a long-time editor of the journal. It has been scanned, formatted, and illustrated by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on the images for larger pictures and more information about both the etchings and the artist.

Portrait of F. S. Haden (No. 2). Source: Salaman, Plate 19.

It is not easy to uncover those homely details regarding any artist that tend to bring him to life as a person. Of course, the etcher's prints in themselves do this, and are after all the reason for our interest in his personality in the first place; but those odd jottings made by his contemporaries, of apparently unimportant facets of the individual, are of considerable romantic fascination; and, personality-wise, of particular academic value. As Ruskin remarked, that sketch of your grandfather may not seem very important while he is yet out and about, but when the old gentleman can no longer be seen up the garden, it has a very different value.

We are all familiar with Seymour Haden's etchings, which he produced with a sort of inspired haste only commencing apparently, after the age of forty — but rarely do we read about him unless in reference to a Whistler anecdote. But Haden also was a Master, and rewards investigation. In fact, he seems to have been quite as difficult a personality as his (successively and progressively) confrére and antagonist. In two articles by the American dealer Frederic[k] Keppel (Vol. I of the P.C.Q. [Print-Collectors' Quarterly] we find numerous fascinating recollections of the Founder and First President of the Painter-Etchers — records of all sorts of quite curiously unimportant little moments that somehow help to form a total picture still unresolved: Haden's gardener works away, stripping the moss from the tree-trunks, and Haden is furious at their new pictorial deficiency, and thinks the man a fool. The gardener grumbles that he was only saving Haden money, and in fact preserving them....

Dasha (Lady Haden). Source: Salaman, Plate 1. Haden married Deborah (Dasha) Whistler (1825-1909) in 1847.

Haden was a proud man: not to say imperial in his manner. "Indeed," says Keppel, "I have never known a man who set a higher value on himself." From: "his collection of the best prints by the older masters ... or the instruments he used when he practised surgery – everything must be of the best." Keppel mentions a discussion at dinner — a matter of varying political opinions — "...he flung down knife and fork, marched out of the dining-room, banged the door behind him, and tramped upstairs to his bedroom. That sweet woman, Lady Haden" — Whistler's half-sister Deborah — "said to me very quietly, 'we shall see no more of Sir Seymour tonight.'"

Lady Haden was an excellent flautist, a fine sight-reader of music, and expert generally in this art. Finding no musicians in the Hampshire village where they had set up house, she organised an orchestra among the local people — "to one she taught the violin, to another the flute, to another the trombone — " In old age, when blindness afflicted her, "I saw her grope her way to her piano and heard her play, superbly, some great compositions by Beethoven and Chopin...."

Frederic Keppel also cites Lady Haden's kindness in allowing him to inter his pet crow at its decease in her garden, and her asking him to compose a commemorative verse. This crow, in those free and easy days, apparently accompanied Mr. Keppel everywhere, and particularly enjoyed "flying with the seagulls on steamer trips across the Atlantic"(!) A curious image, indeed, and a more curious world.

It surely must have been a matter of great distress to Deborah that Haden and Whistler, once (in fact) so relatively close, should have quarrelled so disastrously and decisively later in life. There is the famous incident when Haden was pushed through the plate glass window — there was the affair of Haden re-touching a painting by Legros that he had bought from the artist—then a struggling friend from Whistler's Paris days, who Whistler had brought over to launch (as it turned out, successfully) from Haden's house. Legros stayed to become a leading painter—etcher, pundit, grand old man and establishment figure and a powerful influence on the Society and other etchers.

Whistler's House, Old Chelsea. Source: Salaman, Plate 27.

Despite his hatred of his — it must be admitted — somewhat easily provoked brother-in-law, Haden admitted to Keppel that "if he were forced to part with his Rembrandt etchings or with his Whistlers he would find it hard to decide which ... he would let go. Later on I repeated this statement to Whistler and that modest gentleman calmly replied: 'Why, Haden should first part with his Rembrandts, of course.' "But, according to Sickert, as quoted the latter's A Free House (1947), "with Whistler there was a twinkle."

"As P.R.E.," Keppel writes, "Sir Seymour Haden did great work in maintaining sound doctrine in etching. Nothing was admitted which was 'commercial' in character, and etchings which were done after paintings by other hands were vigorously ruled out." In fact, as regarded the R.E. members, "he ruled them with a rod of iron." However, "membership was eagerly sought for — so much that many famous etchers never were elected, though they tried hard to be."

Haden even undertook an American lecture tour covering the "principal cities from New York to Chicago ... I have never known a man who used more elegant and appropriate language than he." Nonetheless, an American friend of Keppel somewhat acidly remarked: "Well, I heard your English friend last evening humming and hawing through his lecture."

During this tour, Keppel admired the "gorgeous sight of the sun setting behind the Palisades, and mirrored in the Hudson River, and Mr. Haden said to me, with something like reproach in his voice: 'Now, why have I never been told of the beauty of all this?'" Later, "looking about in the crowded train: 'Now, isn't it melancholy to think that nobody among all these people except myself (and perhaps you)" — shades of Whistler? — "has the slightest sense of the beauty of this magnificent sunset?"'

Haden was much taken with a new dish at dinner in a house they visited. What was it? Terrapin. Haden had never heard of it.

"'Oh yes,' said I to him; 'you certainly have heard of terrapin; don't you remember at Church on Sundays, when they sing the "Te Deum," they cry "Terrapin and Seraphim."' 'O, Tut, Tut,' said he, 'I want to hear no irreverence.'"

The alert eye of the artist seemed always attended by that of the surgeon. Haden remarked, concerning one visitor, "your friend will not live long, and when he does go he will go off very suddenly." Asked when? "Just about two years."

"Two years later, within ten days of the time Haden had designated, Mr. Claghorn suddenly fell dead."'

Hands Etching. Source: Salaman, Plate 45. The Latin inscription means, "The sweet solace of labours."

It has been noted that Haden's art is expressed ideally in the medium of etching and drypoint. He does not seem to make preliminary studies — all is drawn direct on the plate. He preferred zinc. According to E.S. Lumsden's printmaker's Bible The Art of Etching: he "thought zinc more suited to the needs of an artist" — perhaps because of the rougher, coarser bite? Apparently, Haden often used the technique of "working in the bath," even out of doors, though this seems difficult to believe. That any artist could sit before a landscape with a bath of acid on his knees, needling through the liquid those parts of the view firstly that require the deepest bite, seems to be carrying a technique into the realms of masochistic pedantry. One would have thought it so much more suitable to bite the plate in the studio — but then, the method does obviate the necessity of stopping-out, and everyone enjoys their own approach best; particularly artists, whose delight in methods that appear to others quite tiresome is well known.

Certainly, by the insights into his personality shown by the few instances quoted above, we can see that once taken hold of a notion, Seymour Haden was the kind of man (and etcher) that nothing could stop.

Fortunately for those of us who wish to visualise the personality of our Founder-President even more clearly, we have several pieces of his writing preserved in the collections of the Reading Room at the British Museum. In an address given to the students of the Winchester School of Art on Dec. 4, 1888, Haden spoke of working out of doors on the spot, and the danger of "the Demon of destructive finish.... Listen to him and you are lost ... take your drawing home, rather, just as it is, and, twenty years afterwards that drawing, as a well-considered passage of nature, will give you more pleasure and satisfaction than if it contained every object of interest in Hampshire."

"Art," said Haden, with some relevance to his equally principal medical profession, "is a process of ratiocination, or, more correctly, since it is half automatic, of cerebration." He exhorted the students: "...when all is said and done your work to be worth anything must be your own."

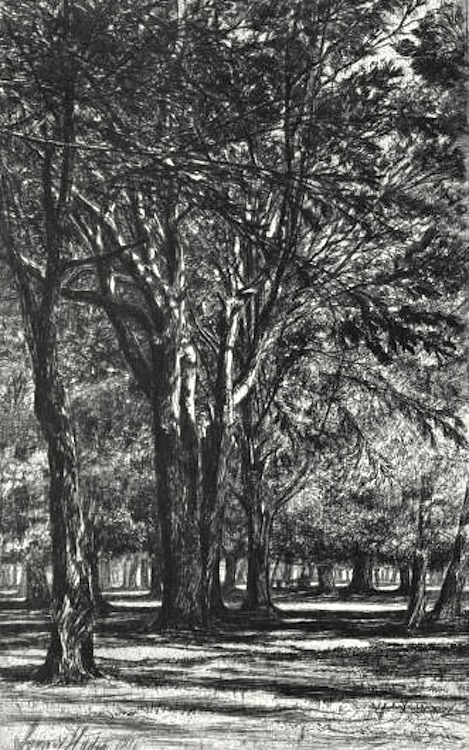

Kensington Gardens. Source: Salaman, Plate 14.

Apparently Haden himself came to art by regarding it as an assistance to the training of his observational powers as a surgeon. In "About Etching" of 1879, he encourages that profession to educate the hand and eye by drawing. As for the etcher: "Every stroke he makes tells against him if it be bad, or proves him to be a master if it be good. In no branch of art does a touch go for so much." He goes on to discuss various etchings and engravings from Durer to Van Dyck and Rembrandt — there is a particularly good reproduction of Meryon's "La Morgue," printed on a grey pastel paper. Haden's sympathies are very definitely with the etchers, although he will admit that Durer as an engraver has no peer: "The comparison of the etching-needle with the burin is the comparison of the pen with the plough." The one is "expressive, full of vivacity — " ... "the other, cold, constrained, and uninteresting ... one ... personal as hand-writing — the other without identity." A strongly opinionated view indeed!

He considers the economic points regarding the printmaker: in The Art of the Painter-Etcher — what it is — and what it is not (1890): "If I were a printseller with the gallery space fitted for the display of this kind of fine art only, to which the public might resort with the knowledge that whatever they found there would bear the imprimatur of the Society — I would soon make my fortune, and ... that of the artist too. As to this last consideration — the interest, that is to say, of the artist, no less than his art — emboldens me ... to beg ... our Fellows and Associates to dissuade their publishers from embarking in etched plates of exaggerated dimensions."

Haden is strongly opposed to the printseller whose concept of etching is the large etched reproduction of a painting. He is also against the highly limited edition intended to increase the price of a short run of prints, and of the publisher who sells this very small number and then destroys the plate. The etcher, he says, should retain his plates: "They are his property, and form part of his estate, and like other property, are cumulative — ." He points out that the earlier etchers printed as required (as the R.E. did until the fairly recent revival of the now huge interest in limited editions in our own day): "To this prudence, in fact, we owe it that impressions from their plates have come down to us at all. If there had been in those days a middleman to treat them as the middleman treats them at present, not only would the artist have found one of the chief resources of his old age discounted, but not a single impression of his work would remain on the face of the earth." Oddly, Haden has not considered the plate that has eventually become re-engraved and strengthened by other hands in order that a subsequent possessor may go on profiting by it after it is actually worn out as regarding the' representing of the artist's original intention.

Of course, Haden could not foresee that today's concept of the limited edition is part of the attraction to the public, in that not everyone in the world is going to own one of the plate's prints, but that a very respectable number will indeed be available, and it is first come first served. Haden's intention in founding the R.E. (as it eventually became with Royal patronage) was, of course, to encourage the etcher who is both the artist and author of his own plates, and who has no connection — apart from the basic technical details of the craft — with the reproductive printmaker.

With some degree of prophecy, Haden suggests that the R.E. publish its own works — which, in effect, is what our members do for themselves today — "There is room now, and bye and bye there will be plenty of room for a lucrative business of this sort."

Related Material

Bibliography

Hind, A. M., rev. E. Chambers. "Haden, Sir Francis Seymour [pseud. H. Dean] (1818–1910), etcher and surgeon." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. 1 April 2015.

"Obituary: Sir Francis Seymour Haden, FRCS." The Lancet. 11 June 1910. Internet Archive. Web. 1 April 2015.

Salaman, Malcolm C. The Etchings of Sir Francis Seymour Haden, PRE. London: Halton and Truscott Smith, 1923. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 1 April 2015.

Created 1 April 2015